ST.GEORGES

ROAD

The New Perlustration of Great Yarmouth front page

St

George’s Park

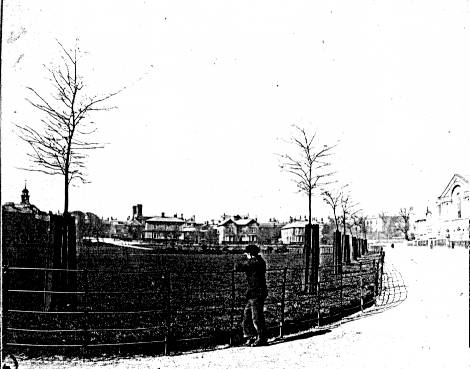

St

George’s Park, Crown Road ahead, looking toward Alexandra Road.

Samuel

Rodker, M.R.C.S., L.R.C.P., lived at No.7 St.George's Road in 1936. Rodker, an Austrian

Jew, with an English mother, then a young man in his thirties, was slim and

blonde, and had a wife and young son. He saw his private patients there in the

house. Most patients attended surgery, any visiting locally was by bicycle. In

the garden of no.7 to this day remains a dug‑out bomb shelter that he

made. Rodker had actually lived over in this country since the age of 10, and

became a naturalised Briton. In the war he was called up as a medical officer.

His wife was a physiotherapist of some kind and gave remedial massage. Rodker

also worked at the General Hospital, and was a heart specialist there. When

Dr.Tan came to Yarmouth, he was at first an assistant to Dr.Rodker, and sat in

surgery wearing a heavy overcoat and scarf, complaining bitterly of the cold.

He was then engaged to a Chinese nurse in London, but a lady he took in as a

lodger, who was a war‑widow (Catherine) with a young child, he in due

course fell for and married. Subsequently they had two more sons. Rodker subsequently took a practice in

Leicester after the war, and Yong Leng Tan took over the practice in St.Georges

Road.

7 St

George’s Road

There

was no appointment system in those days, the patients sat and took their turn.

The fee before the war was 3/6 for an attendance, and 7/6 for a visit. Mrs.Bean

owed Rodker 30/‑, and was unable to trace the doctor after he moved off

to Leicester. (see St.Peter's Road)

The practice at 7 St.George's Road had been here since the surgeon

Frederick Palmer came here and is shown on the lists here in 1863. After him,

Dr.Moxon took over the practice, and was listed here in 1874, followed by

Dr.Vores in 1886. Later Dr. Vickers was to be consulted here, and it is to be

seen that he was driving his car down Southtown Road in 1903, when it caught

fire.*3 Earlier in the same year, ten

persons were summoned for furious driving, that is at over twelve miles per

hour. The following year, Dr.Alfred Charles Mayo was elected Mayor, and drove

the first tram, but he lived up the road at St.George's park house, and was

still shown as Hon.consulting M.O. to the hospital on Deneside, in 1930. It was Vickers that preceded Rodker.

The

air-raid shelter at 7 St Georges Rd.

Doctors

Ley and Smellie had separate premises in King Street on the east side, and

moved into a practice in Alexandra Road together. Dr.Dowding's were on the

opposite side of King Street. Richard Ley gradually retired, and reduced his

practice only to the more elderly patients, on three days a week. There was no

requirement to have absolute continuing care I gather, since all Doctors were

private, and the patient could therefore attend different doctors at anytime if

they so desired. Doctor Smellie was a

fairly tall Scotsman, who developed a chronic lung complaint, and smoked

heavily. Eventually he could hardly get his breath. He died at about the age of

60, still struggling to work. Dr.Tan likewise carried on too long at King

Street after going into practice with Drs O'Donnell and Rutter. He had a stroke

and several heart attacks, and his sight and hearing were failing him. He

retired in 1977, but unfortunately died only a year later.

St

George’s Chapel, 1912

Interior

of St George’s 16th Oct 1912

and

another view

Another

of the old doctors in the town before the war was Dr.Blake, who had his own

practice, but was also a surgeon at the General Hospital on Deneside. Blake had a house and practice in Regent

Road, but his house has been pulled down now. Blake's was an expensive practice

to attend, as was that of Dr.Peers and Mitchell whose surgery was in the house

now occupied by the Waxworks. They exclusively looked after the richer people

in the town. When Mrs Bean had called into Blake's surgery in Regent Road with

her son who had boils and impetigo, he was none too pleased and dispatched them

to the hospital, and with a letter (of complaint?) to old Dr.Connell who had

sent them out for some air. In due course Dr.Connell lanced the boils at the

boy's home (this in 1925, the child aged 10). Doctor Connell was something of a

drinker, but well thought of as a doctor.

another

view of the shelter at 7 St Georges Road

There

were several concrete bomb shelters always available day and night during the

war, in the open ground where the trees are to the west of the art school.

These were half sunk in the ground, with concrete slab roofs above ground. An electric light was on inside, day and

night. These are now buried but still in the ground.

*3

ref.Ecclestone's extracts.