SOUTH QUAY

The New Perlustration of Great Yarmouth front page

South Quay

map -Swinden

..\..\SOUND\BARNES5.WAV

..\..\SOUND\BARNES5.WAV

The South Quay aout 1870, note

the crane in the centre mid-ground (sound clip -Barnes of

Market place)

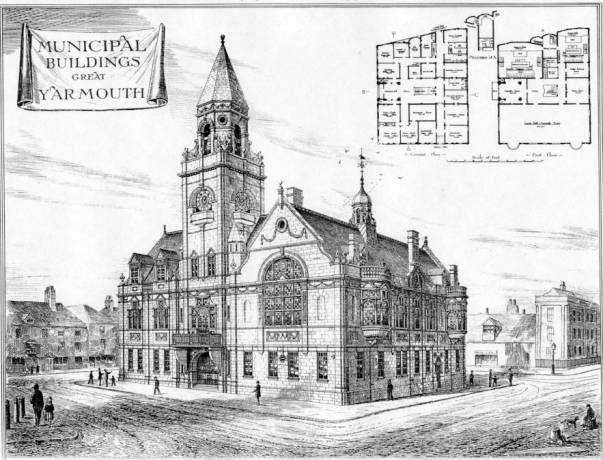

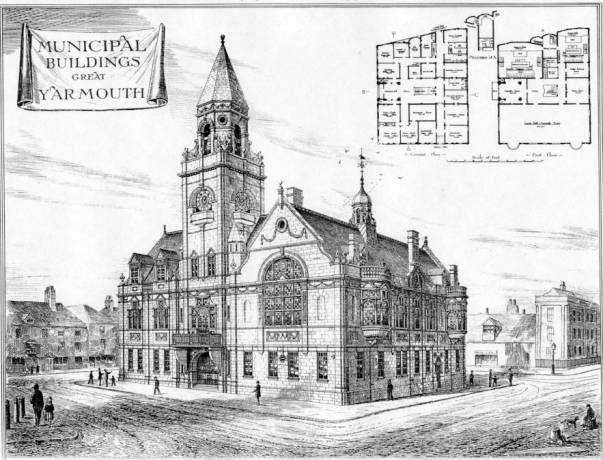

The Town Hall. A new town hall was completed in 1713, replacing the

Guild Hall at the Church gate. Major George England,

mayor and later, member of Parliament, was chairman of the committee who had

this hall built and also the St. George's Hall*1.

This is the town hall of 1713. A replacement town hall was constructed in

1880-82. This had to be shored up, and there are photos by Waller of the props

inside the Assembly room and outside on the west wall.

It seems that the ancient quayside or river bank had given way and was found on

excavation of the foundations. This is the line of a quay Heading or river bank

discovered by Percy Trett on Hall Quay under the "Greasy Spoon", (a

brothel on Hall Quay later called Henry’s Café, see “Hall Quay”) and revealed

again on South Quay in 1994, in the sewer trench that was excavated by Anglian

Water. See items of ancient archaeology in volume 1 New Perlustration.

The new town

hall, as envisaged in the Builder’s journal, before it was built.

The buildings along the quay are described along with their various

rows, and I therefore do not propose to list them again here, but there are

some additional details-

The Yarmouth Mercury Feb.19th.1944 reported that the houses at no.4 South Quay had been bequeathed to the National Trust

by the late Blanche Ann Aldred, leaving it to her sister Mary for life, but

then to the National Trust. In 1947, as reported in the Mercury on Sept 6th.,

the council proposed to demolish the houses in the block including no. 4. (nos.

1-8 South Quay) Alderman F. H. Stone said that there were too many old

buildings that they did not want to preserve. It was fortunate indeed that the

buildings had been passed to the National Trust, there was a national outcry,

and eventually some wisdom seems to have prevailed. The same council proposed

demolishing the shops on King Street between St. Georges and St. Peter's Road.

The judgement of many councillors in such matters is indeed beyond description,

since earlier, as reported in Y. M. 12th. June 1943, councillor Morgan

described the north-west tower as "not even a thing of beauty", and

that too was intended to be removed!

Rear of 25 South Quay, 1898.

YMCA at Crane House.

Crane Quay, opposite to the old Y.M.C.A., now empty

offices to let, was the site of a large crane for hundreds of years. A crane

was depicted here on the Elizabethan map. The public house on the quay,

opposite to the crane was called the "Three Cranes", and passed in 1775 into possession of James Turner, a

partner in the bank of Gurneys and co. of Norwich. They closed the pub., and

converted into a bank. Later, the bank moved to its current site (Barclays) on

Hall Quay, and Sam Barker, one time mayor, acquired the building, had it

demolished, and erected a "spacious house" as residence for his new

son in law, William Palgrave jun.

The first crane according to Manship, was erected

in 1528. This was blown down in 1826. A third crane was in use in Palmers time,

the second having disappeared also. (see also under Row 106)

The Crane, 1950, by Percy Trett.

But, before continuing down South Quay-

Some unique wartime experiences.

A John Crane was drawing master to Palmer at one time. Prior to the

last war a family called Crane were resident in Winterton. John Crane was born

in Winterton on 20/8/31, to Elsie, daughter of Bob King, part owner of

"Ocean Trust", one of Bloomfield's boats. Bob King's boats had acted

as tender to naval ships at Scapa Flow in the war, and then resumed fishing,

but he sold up before the fishing failed. Elsie had a brother, also called Bob,

who kept a shop in Winterton, and in the 1938 floods, when landlord of the

Nelson at Horsey had been flooded out, moved to an off-licence in Ordinance

Road, this was demolished by a bomb, and then he went to Horsey. One day in the war, in the shop in the

village a Fokke-Wulf 190 came low over Winterton, dropping several bombs, one

of which went through the doctor's surgery, and through the outside toilet into

the King's kitchen, where, as it had not exploded, the cat sat on it! Since

this was a 500 lb bomb, if it had exploded, the centre of Winterton would not

exist as it does today. The bomb squad defused the bomb, took it into the

village square, and steamed out the explosive.

Grand-father Crane was blown up on a trinity house ship in the first

war. They were destroying a wreck, but it was full of explosives, and the whole

crew was killed. Crane's sons were all sent to the Trinity house school for

seamanship in London. John's father was at first in the merchant navy, on a

tramp ship, a general cargo vessel, and later went fishing. Two other brothers

were James, who emigrated to Australia, Tom, who went to Liverpool, another

brother that moved away also, a sister living in Brundall, Ellen, who married

one of the Reynolds family of Caister, (see St. Peter's

Road) and another sister who married a garage owner in Kent.

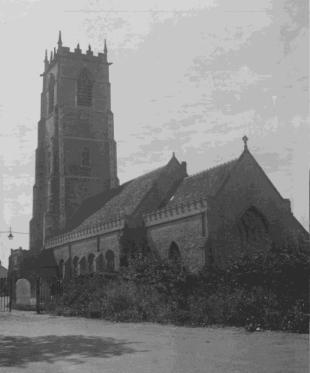

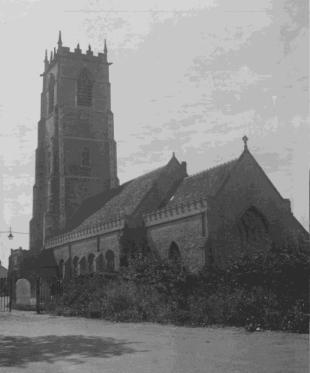

Winterton

Church about 1932

Winterton

Church about 1932

At the commencement of war in 1940, John Crane

was 8 years old and at School in Winterton village. Another boy at school with

him then was his cousin Malcolm King. Lessons in wartime were not always so

frequent, and the boys tended to gather on the beach away from the school, or

in a hut that had been a net chamber. The sand dunes had been mined as well as

some of the beaches, and there was a shooting range, and large numbers of

troops came to Winterton, staying perhaps a week at a time, for training

purposes, not only for rifle practice but also for exercises under fire, with

machine guns firing over their heads. The boys used to know safe trails through

the minefields to the beach. When the wind blew the mines were exposed,

although later they might well be covered by sand again. They also played on

the firing range, and when the soldiers were elsewhere they would gather

cartridges by the sackful. Although most were spent, many were not, and live

ammunition was plentiful. On one occasion the lads obtained a full box of rifle

bullets, dragging the heavy wooden box away through the sand dunes. They became

experts on gun-powder and explosives. Amazingly they were never injured. They

found mortar bombs and shells too, and dismantled them, extracting the powder

to make their own rockets and toy mortars, that really fired and exploded. They

found that in terms of the powder there were three types of 303 cartridges.

They would fit the bullet into a hole and then break the end off the cartridge.

Inside they found "black ball cordite", "black cordite",

and "stick cordite". They found that there was not much fun to be had

from the black type, but the stick cordite was more useful. To make a home made

bomb, they would use a "Camp coffee" bottle with the lid off, put

some cordite inside, and then lay a stick of it over the edge and light the end

so that it acted as a fuse, and when it burned through it got to a stage when

its own weight would tip it into the jar and set off the rest with a good bang.

One day, the cordite, usually set smouldering with a cigarette so burning quite

slowly, was by-passed entirely, and the cigarette fell directly into the

bottle, which blew up instantly, glass flying everywhere, yet no injury was

sustained! The boys found hundreds and

hundreds of live rounds, and stored the cordite that they extracted in a

biscuit tin. Sometimes they would put a stick of cordite onto the stove in the

kitchen at home, and it would go fizzing around the room! One day the stick

jumped off the stove right into the biscuit tin. The kitchen was instantly

invisible due to flames and smoke. The boy's mother was not at home! Another trick was to use a two inch mortar

flare; there were various types. This particular arrangement was to dig the

flare into the ground, knock the top off, ram it in to made it harder, and then

set light to it. There was then an extremely loud bang, and the flare would be

projected some two hundred feet into the air. These tricks were routine over

most of the five year period of the war, and yet the only boy ever hurt was the

policeman's son, when someone threw a smoke-bomb onto the fire, when it blew out into his arm, so breaking it.

“The Gang” on Winterton beach,

just post war.

When it was all clear, the boys would trek across the mine-field to the

beach.

Ships were often blown up out at sea, and all sorts of wreckage would

find its way onto the beach. One day a large tea-chest was washed onto the

beach, and when it was opened up, it was full of Chinese money, packed full -

probably thousands of pounds worth. Another day, barrels of fruit pulp were

washed up all along the beach. Sometimes in the evening the E-boats were

inshore on the surface, shooting at the shipping with their deck guns.

At school there was a boy posted on the roof to spot enemy aircraft.

One day when they were on the sand hills, an enemy Heinkel came out of the

cloud at about 300 feet, and going over the youngsters the crew just waved to

them, as though one of their own. The boys gave the sand hills names. One was

"Blue Bird hill", looking like the racing car. One misty day there

was a huge explosion nearby, then several more at close proximity. Shelling had

started on the range!

“The Swimmers” – Russell,

Ricky, another, John, Buddy, two others

and Audrey.

At night the children would gather at the cart shed, quite a crowd of

them of all ages. They tried to avoid a boy called Percy, as he used to tell

his mother what they were getting up to! Perhaps twenty children would gather

at a time. Sometimes they picked sides and threw stones and bricks at each

other in mock wars.

The shells that they found, they would hide everywhere and anywhere.

One stash was in the coal shed. One day when mother put some coal on the fire,

the front of it was blown off. "Cor, this is funny coal" she

said! The door holding the coal, and

the grating in it was blown right out of the range.

In one place on the range where the gunners fired bren-guns over the

heads of the soldiers, there were millions of shells in a hollow. The boys

would rummage through for the live ones, and were un-interested in the spent

cartridges. One day they took several boxes of 9mm shells, boxes of about 2x1x1

feet or so in size, with rope handles, and buried them for safe keeping but

were unable to find them again, and they may well be there to this day. There

had been an anti-tank trap there, so they might be quite deep.

The boys would pinch thunder flashes from the back of the army lorries.

The trick with these then was to light one which had been weighted by filling

the hollow end with sods of grass, drop it down a length of scaffold tube,

count five, light another, drop that down the tube the other way round, and

then the explosion from the first would blow the second high into the air where

it would detonate. The boys thought that the soldiers were pleased not to have

too many left to use themselves! The

thunder flash had a strip on the side like a matchbox, and a match-like end,

that enabled it to be lit. Sometimes the boys set off smoke bombs in the middle

of the village when the washing was out. There was so much smoke that no-one

could see a thing! For a ten year old

boy this was bliss indeed

The sand in the mine fields would shift around. One was thought to be a

dummy minefield by the lads. Sometimes the mines would be uncovered, and

sometimes they might be three feet deep. Of course the adults never knew what

the boys were up to - they would have been distraught. This particular minefield they walked through regularly, and

none of them was ever blown up, but whether it really was a dummy field or not

will never be known. There were wires leading from one mine to another that were

sometimes exposed. Some boys crept around the minefields avoiding the mines to

collect the small parachutes that were attached to the two inch mortar bombs.

Several dogs had been blown up in the minefields though. The minefield was a

strip of land immediately inland from the beach, about 50 yards across. The

parachutes were fun to play with when a weight was attached and the string and

parachute coiled up. These parachutes were about two and a half feet in

diameter.

The best time was to be when out at night. Crowds of the boys went up

the cart sheds beside the pubs. They messed around by these sheds at night, but

on the range the tracer would be fired, and they could get around out of sight

of the adults.

Other favourite games were making bicycles from scrap parts, racing tin

cans down the sand hills; and crouching up inside old rubber tyres that were

rolled down the sand hill with the boy thus inside it. One day Mally (Malcolm King), George, and

John found a stove in the far plantation, dragged it to the near plantation,

and there they cooked pheasants eggs by boiling them. These were children's

games when the imagination was used to great advantage.

Winterton scene, about 1935, by

P.E. Rumbelow. Man sat on the granite stone.

There were gangs in the village, the boys would be affiliated to one

gang or another such as the Smith's gang, and used to fight each other. If an

outsider came into the village the word would be round like wild-fire and they

would appear from everywhere to "ston-em-home". They would drive any

other child out by throwing stones at them. The children of one village could

never go into another, even say from Winterton to

Martham. One day mother sent John to the tally man in Martham on father's

"biceckle". This was a frightening experience indeed. He had to

"run like hell", or else the boys in Martham would have given him a

"good turning over" if they caught him. Every village was the same,

and hence very interbred in those days before the war. The only thing that put

paid to it was the war, when the soldiers came, and the girls in the village

fancied the soldiers. A number of the girls married soldiers. Regiments such as

the Gloucesters and the Berkshires would visit on training exercises for

perhaps a week at a time.

Gable end of thatched house at

Winterton, 1.8.35.

On the cliffs were gun emplacements with 14 inch guns. There were

search lights also, and some other guns positioned on the beach. There was a

narrow gauge railway with a locomotive that was used to pull wagons laden with

boxes of shells. The boys played on loose trucks, taking them off their

coupling to the locomotive, pulling them to the top of a hill, then sitting in

it, allowing it to run down the hill and up the other side. One they called

"jumping jenny" as it used to jump off the tracks at the speeds the

boys used to go at. One time there were

two trucks running down from the beach end, one behind the other, and another

boy let a truck go from the other end at the same time. There was a violent

collision, and John who was positioned at the front of the leading truck, was

unable to get off. The truck threw the lad through the air under the leading

truck; then the truck behind collided also, and the boy went through between

its axles. In the finish he was cut on the leg and his head. A soldier nearby

picked him up and carried him to the nearest house, where the doctor was called

to stitch his wounds. Evidently the soldiers allowed the boys to play there

with little restriction. Shortly after, during the Battle of Britain, there was

a raid on the village, when the bombs fell onto the sand-hills, where the

marram grass was set on fire by incendiaries. This great fire could be seen

from afar, and attracted more and more bombs. Next day it was seen that every

square yard had been hit by bombs. "Lord Haw Haw" announced on German

radio that Yarmouth had been razed to the ground in the night. It appears that

this would certainly have been so, if it were not for the marram grass on

Winterton hills.

There were four large net chambers in the village, buildings with two

floors, the upper quite stout, where the soldiers were billeted. Some of the

houses in the village were converted net chambers. The soldiers had straw

mattresses on the floor. They used paraffin stoves outside to cook and boil

water. The flame was projected along under the billy cans. Nearby the net

chambers were the tanning tanks that had been used with a fire underneath to

coat the nets in a hot tarry liquid.

And so to sea:

After the war John Crane, leaving school, went to sea as a cabin boy on

King's boat. They went initially into Felixstowe, but on leaving that port the

engine failed. Removing a plug from the engine, it simply poured out water, so

was unrepairable. The boat drifted south for three days. Eventually a huge

vessel stopped beside them in the Thames and radioed to land. In due course

they were towed into Ramsgate by the lifeboat. This was not a good first

experience at sea however and it was to be his last. The water had all been

contaminated by salt, and the boat simply drifting about and bobbing up and

down as it pleased. The rugs were burned to try and catch attention, and flares

when the ferry passed, but all to no avail. At that time the fishing had been

still in full swing, indeed there was a glut of herring for five years or so

after the war before it became over fished and the industry failed quite

suddenly.

Crane senior was on a drifter during the war that was fitted out as a

mine-sweeper. There were cables running around the outside of the vessel that

induced a magnetic field so as to set off the magnetic mines. One day coming

into harbour further south, they came up against one of the new acoustic mines

and the vessel was blown to pieces. Only two men survived this. The wife of one

of the dead men later drowned herself in the Yare. Crane himself was

subsequently in charge of the tug the "George

Jewson". During the war the river was home to a number of motor torpedo

boats. The captains of these tended to be rather reckless, and could not be

trusted to come in and out of harbour safely, so the "George Jewson"

was instructed to tow them in and out and so ensure the safety of other craft

and the sea wall.

Ignoring the Air raids:

During the war some of the young lads at

Bunn's warehouse, on the opposite side of the river, kept watch up on their

roof. After some passage of war, the staff being very busy with animal feed,

they tired of abandoning work for the incessant sirens, that frequently went

off, yet nothing followed. Rather than rely on the sirens, even though there

were two types of siren, one to warn of activity in the area, and a whooping

type of call that indicated aircraft actually over the town itself, they

devised their own system, taken when this local warning sounded. Three or four boys were rostered by Mr. Bunn

to take turns and climb up a ladder to the roof, and another short ladder up

the chimney stack, and observe to warn if the aircraft was actually headed in

their direction or not. Arthur Postle or one of the other youngsters, would be

sat on top of the roof with an electric bell-push to sound the alarm if there

was any real danger, when everyone in the office would dive for cover.

..\..\SOUND\Postle9Bunns

alarm system.wav

The boy would simply be hanging

onto the chimney-pot! One grey and

misty day, early in 1941, Arthur was

despatched to take watch when the crash alarm sounded. There was the sound of

an aircraft, and looking in all directions through the drizzle, he could see

nothing. He turned to look north, when out of the cloud appeared a Heinkel 111,

coming over the Haven bridge, at a level below the town hall clock, and since

the aircraft had now passed, Arthur did not push the bell-switch, but the plane

released five silver bombs, which fell horizontally

into the river without exploding. The five bombs fell in the region of the cranes, and have never been reported or

found. It looked as though the plane was aiming them at the cranes, but hit

nothing.

..\..\SOUND\Postle8bombs

in river.wav

Digging under fire!

It was at about this time that the corporation decided to construct

another road at the back of Southtown.

Until then there was only the

one road to Gorleston, and Suffolk Road was constructed then as an alternative

route. Fortunately too, since shortly thereafter Southtown Road was made

impassable by bomb damage. The dig for victory campaign was initiated, and the

allotments created in Cobholm and

everywhere that there was spare ground that could be dug up. Young Postle was

digging at the allotment one morning, when a DO-17, having attacked Jewson's

premises, where a ship was unloading timber dropping a bomb missing it, but

damaging the quayside, and killing two dockers. The pilot could see no other

activity bar the sight of Postle digging, and so made a raid on the allotment,

strafing it with machine gun fire.

..\..\SOUND\Tuck6childrens

games.wav

Children's Games some are described in the preceding paragraphs, but

the south quay was formerly a favourite place for children to gather and play,

since it had an avenue of trees in the middle and little vehicular traffic

compared with today. Before the last war the children in this area would also

wander down towards the harbour's mouth and onto the open ground of the south

denes, where barrels would be piled on which to play, but also a man might be

found burning debris such as broken barrels and fish baskets. Walking a

distance was thought nothing of, and they would play cricket or football down there,

since the power station and the big factories had not yet been built. The

children would climb up piles of barrels higher than a house without complaint.

Baby might also be in care of the older ones, and taken out on a trolley or

antiquated perambulator. Children's games in the thirties used cigarette cards

for currency. They were sometimes stood up like skittles and the child that

knocked them down acquired them. Darts were popular, as were marbles. an alley

was the name for the big marbles, again the winner acquired the marbles.

Cigarette cards were fixed to Inkson's fish-house wickets, and darts thrown.

Whoever impaled the card won it. "Knock-a-doory-bunkum",

..\..\SOUND\Tuck8knock

a doory bunkum.wav

knocking on people's doors and

running away, was good sport to the children of the Middlegate area, very

annoying for adults, though harmless enough. Mainly in out of the way rows, the

children would ring a bell or knock on a door and ran away as fast as they

could. Mind you, should they get caught, they got a thick ear, and if they

cried about it at home, another one. In the fishing season there was more

traffic on the south quay, but otherwise spinning tops could be hit in the road

without any concern. Skipping with one each end and one in the middle was

common. To a child then, the Methodist Chapel at Priory Plain was fascinating,

and a site of imaginary games and exploration. When empty children could still

find a way in to explore and play out their imaginary games.

This house on South Quay had a

date on the mantle piece of 1598.

Sound -description of the bombing of the Paget’s old house at 59 South

Quay..\..\SOUND\POSTLE6.WAV

The

paddle-steamer from London landed summer visitors on

the quay, and townsfolk would attend so as to offer them accommodation in the

best room of the house.

Cecily Barnes on meeting the

boats

South

Quay, looking North from Row 111, 1987,

(before being paved, cars parked everywhere).

Second

from right is No 25, third from right is Crane House. Then road to Library,

then Port and Haven Commissioners.

Much

the same view, about 1930, by P.E.R. Note the house once built by Andrews the fish merchant, shored up.

and

slightly further North.

note

the buildings across where now is Yarmouth Way.

Corner

of Yarmouth Way, 1987.

The

Gallon Can, 1987.

South

Quay, flooded, February 1993.

and

looking South, about 1900.

The Sceptre Public House

The Sceptre Public House

Arthur Greaves at the door

of “The Sceptre”.

At nos.68 and 69 South Quay was the "sceptre" public house on the corner of Friars Lane. (N.W. corner)

Arthur Greaves was the landlord here in the 30's. He came to Yarmouth from London, having previously kept the Kings

Arms at Wood Green, and the "surprise" at Chelsea. He also in-between

those took the working man's club at Twickenham. He was thus an experienced

publican and leased the pub. from Bullards, it being one of the very few that

were not owned by Lacons. He brought his wife and young daughter Lucille with

him to go to the Theatre Stores pub. at Norwich, but feeling that to be too

rowdy he came to one of their three Yarmouth pubs, which he took for some 5

years.

Lucille back left, Grenville, front Left, baby Rose in grandmother’s

arms.

Their daughter Rose was born here, and then they moved to take a boarding

house in Victoria Road, which he bought in 1936. In the first war he was in

Jerusalem with the 21st lancers, a cavalry regiment, and lost the sight in one

eye. The best trade in the sceptre was when the Scots fishermen were in town,

and Mrs. Greaves put some of them and holiday boarders up in the rooms above

the pub. which were on the two upper stories. Above the Pub. itself was a large

first floor room that served for functions of such groups as the Masons and the

Buffaloes. Mrs. Greaves looked after the lodgers, there were lunches and

evening meals to provide as well as the bed and breakfast.

Rose,

outside the Sceptre.

Rose,

outside the Sceptre.

In all there were seven in the family. The children were Lucille, now

Duffield; Sid, now at Kennel Loke, and who worked at one time on the old Queen

Elizabeth liner; Grenville, who worked at Bunns and then Spandlers as a senior

manager in the haulage business; Dorothy, now Pettit De Mange, living in

Lowestoft, and the baby, Rose who married into the Smithdale family of

Lowestoft, who had an iron foundry in Acle.

Sceptre on the left, 1990.

The Smithdale line at Acle started with Thomas Smithdale, who had six

sons and had moved from Ramsey. They made pumping machinery and drains, and at

one time had a mustard business before Colmans started up. The foundry was at

Acle behind the manor house that they owned there, and that smelting furnace is

now to be seen at the museum at Gressenhall.

In the photo outside The Sceptre, Alf Walker was Mrs Amelia Greaves'

brother, who was a carpenter, now of Lowestoft, but who came to Yarmouth with

the rest of the family. The Greaves family moved to a boarding house at 28

Victoria Road, now the "Garrick" Holiday flatlets, prop. D. A.

Knights. (see under Victoria Road) Mrs. Walker never lived in Yarmouth, but

visited from her home at Southall.

when the south part of South

quay was demolished (now flats) an undercroft was discovered

photo’s by P.E.R.

Robert Postle's description of the undercroft

Robert says the undercroft is still there, filled in

Drury House appears to have been the third south

from the corner of Friars Lane. The house was a Jacobean one, erected at the

beginning of the 17th. century by Roger Drury. The Drury family acquired most

of the property of the Blackfriars monastery. The whole front was faced with

square-cut flints. and dressed with stone. The centre porch had a room above,

and over that at one time were the

figures of three naked boys, cast in lead. Evidently the rainwater was passed

by them in a way you can imagine. The house was shown on Corbridge's map with

an avenue of trees in front that led right across the Quay to the river. The

house was occupied during the 17th. century by Major Ferrier. In 1777 the house

was owned by Anthony Taylor, and following him, the owner was Jacob Preston,

mayor in 1793 and 1801. On the day of his inauguration as Mayor for the third

time, in 18134, Preston officially opened the new Regent Street. At a radio

interview on 28th. Dec. 1994, I questioned a man called Keith, who phoned in,

and admitted to being on the crew that actually demolished the property. He said

that the house was then in the worst state imaginable, having been set fire to

by occupants who used the panelling for firewood. Afterwards though, on

31/12/94, Percy Trett told me that the house had belonged to Yarmouth Stores.

The historical building Company managed to acquire it. The directors used to

meet at Lovewell Blakes office. They included Col. Beevor, Ecclestone and

Millican and Meldrum. When Meldrum died, Trett was elected in his place, but

unknown to him, the others had taken a decision to demolish it. Trett,

horrified, was unable to prevent the act. The house had a black and white

marble floor in the hallway, and was extensively panelled throughout. It had

several of the Yarmouth "Angel" cupboards, which were somehow saved

from the demolition team and sold, as was the staircase, by Malcolm Ferrow. The

staircase was reassembled at Blickling Hall, and is still to be found in the

building with the tea rooms. Apparently the fire raisers were unauthorised

squatters.

Drury House

Drury House

South of Drury house, the ground between it and the south gate, which

had belonged to the Black Friars, was purchased by John Berney in 1671. The

last house before the south gate was a pub that in 1772 was called the

"Dolphin", then called the "Ship on the stocks", and then

the "First and Last".

The South Gate is depicted as a ruin in an original sketch given to P.

E. R., and contained in his diary for 1941-2. It shows the western tower of the

gateway remaining, the eastern part and the arch having disappeared.

The advent of

North Sea Oil

Further down the Quay towards the harbour's

mouth now, have in recent years been based a number of Offshore companies. The

quays are controlled by the Port and Haven commissioners. Wimpey Marine of

London acquired rights over several sites on the quay in the 60's. Sites were

let to such offshore companies as Haliburton and Brown and Root, which are

American in origin. A man called Reg. Butcher came to Yarmouth to investigate

the site in the days when the only remaining shipping concerns were such as Lee

Barber, Jewson, Palgrave Brown, and Bunns. Timber and grain were imported, but

there was no offshore industry until 1964. Pipes were then stored and shipped

in and out, and the ships servicing the rigs were introduced. The supervisor's

job then meant being on call 24 hours a day, and carrying a "bleep".

B.P. was another company to arrive in the early days. In 1983 Wimpey Marine

took over the sites of Brown and Root, and in 1988, Inspectorate E.A.E, a Swiss

based investment company combined with Francis Holmes' East Anglian

Electronics, bought up the pipe yards, and created a new business park. Later

Francis Holmes' newly formed company, Ventureforth, bought the Yarmouth sites

from Inspectorate, and they became entirely locally controlled.

The Smithy

Off Southgates Road in 1938, at no.19,

were Plane R.& J., ship smiths. John Plane worked there very briefly, and

described the work. The owners were his father John and Uncle Robert. (another

brother Billy, was a capstan maker) In the Smithy was a forge, burning coke,

and forced with bellows. The iron was softened and worked. Perhaps two pieces

at once would be made white hot. The two pieces would be joined by hammering

them together whilst white hot. John Plane snr. went blind due to the white

light off the hot metal. Then it would be heated again, and finished off with

more hammering. Chains for ships anchors were one of the items made. The iron

came from a foundry further up the Quay, on the site of Pertwee and Back's premises.

Coke was used in the furnace, and there was a hood over it, but no doubt gave

copious fumes all the same. This smithy was up the little passage that is

beside the Albert Tavern. The business then owned by Albert and John was

inherited from their father. The forge was on the south side of the passage,

although there was a second forge on the north side, together with the iron

store. Here now is the warehouse of the

East Coast Electric Co., on the south, and a garage on the north. At

lunchtime, the men of the forge used the Albert tavern. There is a passage

behind running to Exmouth Road.

Winterton

Church about 1932

Winterton

Church about 1932

Rose,

outside the Sceptre.

Rose,

outside the Sceptre.

Drury House

Drury House