††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††† †††††FRIARS LANE†

In

1271, Henry III, gave the Blackfriars permission to take in a piece of ground

five hundred feet square, called Le Stronde. The conventual buildings were

finished in 1273, and in 1314, Edward II gave them permission to enlarge their

property. Thomas Fastolfe, who had the keeping of the passage in the King's

name, under Sir John De Bottetout, the Lord Admiral in 1295, was a principal

benefactor. Correspondence to and from Thomas Fastolfe can be found in the

Papal letters.

Skull

found at Blackfriars site by Rye and Trett.

In

the cellar of a house on the south side of Friars Lane, was seen built into the

wall, a stone gargoyle, which no doubt came from the church of the Black

Friars, as also did some corbels built into the face of the south west‑tower.

There is a drawing of these opposite p. 429, P.P. vol 2.†

About

the year 1525 "the church and quere of the backfriars was burned with

fire, and before the end of that century the walls were pulled down, and the

very foundations digged up and dispersed to other uses." (Manship)†

In

the excavation of the Blackfriars Monastic Church site at Friars Lane.

Edmund

Hercock, was the last Prior, and by him the convent was probably surrendered.

In 1542 the whole site was granted by Henry VIII to Richard Andrews, who seems

to have been a dealer in this description of property.†† In due course a more extensive portion of

the precinct including the monastic gardens, were conveyed by Nicholas Mynne,

to Roger Drury, the second son of William Drury of Bestford, by Dorothy his

wife, daughter of William Brampton of Letton. Having taken up his residence in

Yarmouth, he was made a Free Burgess, and elected Bailiff in 1584. He

represented the town in Parliament in the memorable year of 1588, was again

Bailiff in 1593, and died in 1599, buried at Rollesby. By his will he gave the

Blackfriars (lands) to his second son, together with his lands at Rushmer,

Mutford and Bradwell.† Roger Drury the

second son, who became possessed of the Blackfriars under his fathers will,

granted in 1618, a lease to Hamon Claxton of Gray's Inn for the term of 1000

years, under which, the property, much divided, remained.††

Mark

Trett in the excavation (see also in Victoria Rd for Trett family)

At

the north‑west corner of Friars Lane there was a fine old house, which

early in the seventeenth century was purchased of William Browning, by John

Robbins. He was of a Warwickshire family seated at Claverton, Stratford on

Avon, and settled in Yarmouth as a merchant, where he acquired a considerable

fortune. He entered the corporation, and took an active part in the municipal

affairs. In 1626 he opposed Neve's scheme for changing the local form of

government so often referred to. In 1634 he filled the office of Bailiff. By

his will made in 1639, after bequeathing 5 pounds to the church, 5 pounds to

the haven and 5 pounds to poor, he devised his Warwickshire property to his

eldest son John Robbins, together with a brewery in Yarmouth, and bequeathed

his Friars Lane house to his second son Robert Robbins. The latter pulled down

the old house and built another, which had a cut‑flint front with stone

dressings and dormer windows to the roof.†††

†††

Here

in 1655 Robert Robbins filled the office of Bailiff. He died in 1659. John

Robbins his son, succeeded to the Friars Lane House, in which, while filling

the Office of Bailiff in 1692, he had had the honour of receiving and

entertaining William III, when his Majesty landed at Yarmouth on his return

from one of his visits to Holland. Great preparations were made to receive the

King, and Mr Palgrave went to Sir Thomas Allin at Somerleyton with a letter

from the Bailiffs begging the loan of his coach and horses. The King upon

landing was attended upon by the corporation in their robes of office, and

conducted to Bailiff Robbins house. Colours (flags) were displayed, guns fired,

and the militia raised. In due course, Robbins lost, spent or squandered the

family fortune, and died in 1707, aged 64.††

massive

stone pillar from the monastery.

Early

in the 18th.century, the house became the house and residence of Andrew Bracey,

and in 1734 was conveyed via Charles Le Grice to Edmund Cobb, who in 1754

settled it upon his wife. Cobb died in 1787 leaving two daughters, Ann, the

eldest, married William Hurry, and Mary, the youngest, married Thomas

Ives.†† Early in the 19th century, this

house was occupied by Admiral Lord Gardiner K.C.B., when in command of the North

Sea Fleet, and here died on the 22nd. of March 1811. Charlotte, Lady Gardiner,

his wife. It had been purchased in 1808 by Capt Parker R.N., afterwards Admiral

Sir George Parker K.C.B., who after Lord Gardiner left Yarmouth, resided here

for nearly 40 years, and then and for many years after, the ground in front was

open down to the river.††

In

1865 the house was purchased by the local board of health and partly demolished

for the purpose of widening Friars Lane. On removing the white bricks by which

it has been cased a fine old flint front was brought to light. The ornamental

ironwork still remaining upon it. The undemolished part of the house was

rebuilt and turned into a liquor shop called the Sceptre. The Sceptre public

house, occupied before the second world war by the Greaves family, is further

described under "South Quay".†

The next house fronting south stood within a paved court, having next to

the street a row of trees. The greater part of the court was added to Friars

lane. This house was, with many others surrounding, successively the property

of families‑ Robins, Bracey, then Le Grice, and in 1734 was conveyed to

Edmund Cobb.†† William Hurry resided

here for many years and died at the house of his son in law Mr. Morris of

Normanston, in 1807 aged 73. David Tolme who married one of the daughters of

William Hurry purchased in 1808, and resided there until his death in 1825,

aged 72.†

Graves

outside the Sceptre, 1930ís.

First

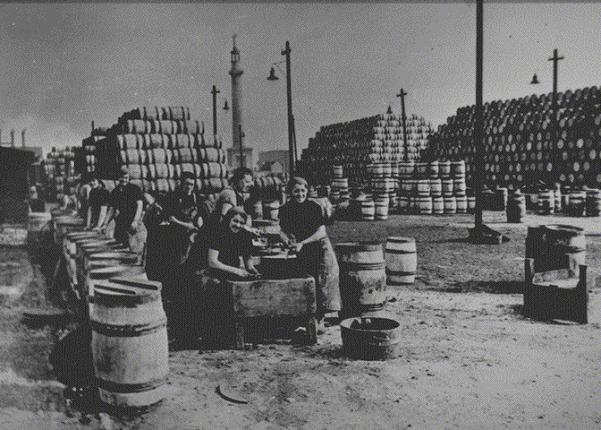

into Friars lane from the Sceptre, on the north side were the fish houses that

belonged to the Tuck family in 1930. Sutton's were the largest firm curing

fish, but there were many smaller businesses, such as Tucks, some with only one

small smoke house. Suttons had very large fish-houses to the south and there

were huge expanses of ground used as barrel stores on which the youngsters used

to climb and play.

Frederick

Jarrad Tuck, the fish curer and exporter and his wife Elizabeth had two

children. The eldest, May Alice was born at no.5 Shuckford's buildings on

28/9/1921, beside St.Nicholas Road, and the younger child, Ronnie, was born at

Mariner's Road (7th.Oct.1925), where Fred had a fish shop. The other children

in the family were Fred, a guardsman in London and Tom, who emigrated to

Australia. The fish shop was disposed of when they moved to his premises on

Friars Lane, and they lived in the house there beside the smoke house. Much of

the fish was sent to Italy and Egypt. Elizabeth also worked in the fish-house,

putting the herring onto the "speets" prior to curing. Fred's father,

George William,† had been a fish curer

before him with premises at Middlemarket Lane. Occasionally the children would

help assemble the wooden boxes from Porter's box factory. The fish when boxed

up would be sent straight off from southtown station, with the labelling

stencilled on the side. The fish when bought from the fishwharf would first be

steeped in brine for some weeks before being cured. The steeps in the Friars

Lane premises were built up above ground, of concrete. There were some four or

five of them, and a very large quantity of fish could be stored for smoking in

due course. The house at no. 5 Friars Lane, was between the Sceptre and the

fish house. Further up the road on the corner of Middlegate, was a public

house. The house at no. 5 was of three stories, quite symmetrical in appearance

from the front, the door flanked on each side by a window, and with three

windows on each floor above. The front door opened directly onto the street.

There were six bedrooms, with two at the back facing the fish house. Two on

each floor faced Friars Lane. On the ground floor the two main front rooms on

either side of the hall likewise had a window out onto the road. At the back

was a large kitchen (with range and gas cooker) that was very dark due to the

fish-house behind. There was a back yard and a passage leading onto Friars Lane.

Heating was by coal fire, and lighting was gas. There was no running water,

except a cold tap in the kitchen. Visitors were taken in during the season. May

joined the A.T.S., on a search-light unit, and then as a clerical worker in the

war, posted to London and then Egypt. Fred and Elizabeth evacuated to

Filby.† In the walls of the house at no.

5, there was a lot of salt in the walls thought to have derived from brine

getting into the ground from the steeps. One of the rooms in the house had been

boarded to cover over the salt, but the nails rusted and showed through. The

rooms had fine high ceilings. Elizabeth would let no-one into her kitchen at

any time.

Smoking

the herring

Fred

had to work at night, rising from time to time to kick the fires together in

the fish-house. There was a good stock of fish still in the steeps after the

season had finished, so that when an order was received, say for a thousand

boxes of herring there would be plenty of fish available to fulfil it. Fish

would still be available in March, and perhaps only run out for a very short

period in the summer. Fred also had a shop in the amusement arcade on Marine

Parade, selling boxed fish to summer visitors. When business was brisk in the

autumn there would be perhaps five staff working at the fish-house. One man

would be responsible for taking the fish from the steep.

Another

would wash them in a basket. The fish would then go through to the

hanging-house where the women would put them onto the speets, after which a man

would place the speets across poles called the "loves", hanging them

across the smoke house, high above the ground. In a big smoke house there might

be perhaps four fires. If "whites" were being produced, then there

would be wood fires, but if the end product was to be the red herring, the

sawdust was used all round the walls of the house. It was lit with fine wood

dust - "shruff"- and with the saw-dust on top the fire to produce

reds was kept in for two weeks or so. Nowadays red herrings are produced by dying

them before smoking, but then they were produced by long slow smoking.

With

several smoke houses being used the process was more or less continuous, as

they moved from one house to another, filling one and then emptying another.

Upstairs in part of the fish-house the boxes were kept, and it was possible to

open and close shutters on the windows to regulate the air and smoke. These

shutters were called "wickets". There were ropes running up to the

top wickets over a pulley, so that the door or wicket could be raised or

lowered according to the wind direction. To get up the smoke house and hang the

speets was not easy. The loves were stout pieces of timber running from one

wall to another, but these were positioned for the herring and not so as to

make it any easier to climb up! The loves would hang all the way up to the top

of the building, and were just the right distance apart to allow the speets to

rest on them. Each speet would have 18 or 20 herring on it. One man would be

standing on the loves at the top of the building, with another below and yet a

third below him, so that the speets could be passed up from man to man. This

was not without danger, and sometimes a man might slip or lose his balance, and

be badly injured or even killed by the fall. There were generally three levels

of loves in these particular smoke houses, in which the top levels would be

filled first, then working across the next level down, and so on. The fires

when lit would need attention every two or three hours until the herring was

fully smoked. The fire would be kicked together, being lit upon the ground, and

more wood put on as necessary. The herring when smoked and ready to be packed

way entirely dry, so the fires could not be too fierce or else the tails of the

fish on the lowest speets might catch fire, so ruining the fish. Indeed with a

small house the lower loves would not be stacked with fish at all.

Immediately

beyond the Tuck's smoke houses, was a fish-house belonging to Mr.Beezor. Robert

Beezor however dealt with fresh herring that were† packed in ice and sent by rail, or sold on a market stall. Past

Middlegate on the same side of the road was yet another fish-house, the

Scottish curer's (H.Inkson). Stimpson's was a general shop including grocery. A

bootmaker, William Algar, was to be found on the corner of King Street. On the

south side of Friars Lane was a cheap and very quick hairdresser, Mr.William

Dyball. George and Harry Porter from no. 8 worked in Tuck's fish-house.