THE FISHING INDUSTRY

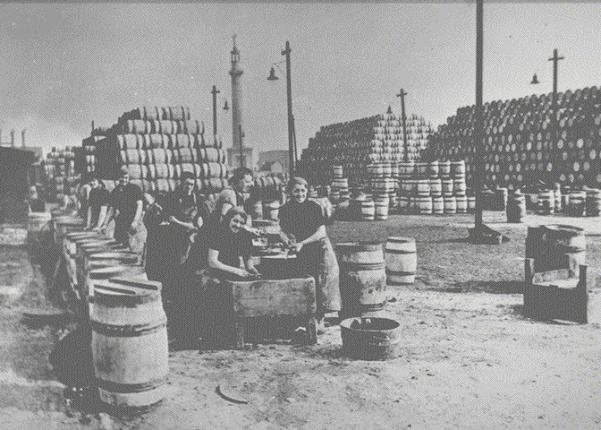

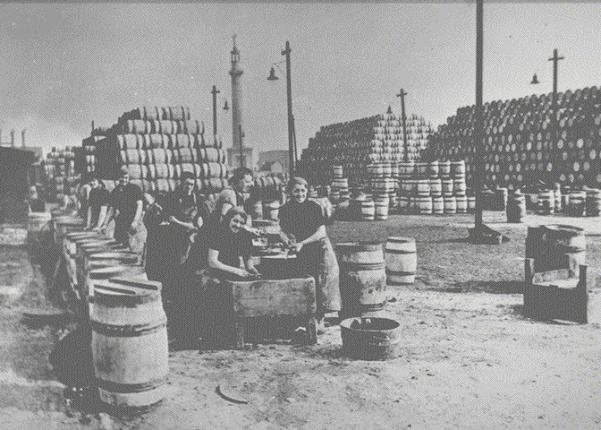

Girls salting fish on South Denes. South Denes was an open space, thousands of barrels are stacked up. The fish were gutted, washed and stored in barrels in layers of salt. Edward Ist had herring supplied in this way.

The great fishing industry that developed during the Middle Ages, resumed after the second World War, only to result in a rapid decline in fish stocks due to the new methods and machinery. Before the first world war however, it ranked as the premier herring port, and from late September or even earlier, large catches were brought into the harbour.

In the Middle Ages, the fishing in Yarmouth was all important. Herring was a staple in the diet, and had the great benefit of being well preserved in salt. Thus herring was stored and transported by the barrel all over the country. Edward I, whose bust was displayed high inside the roof of St. Nicholas Church, ordered 18,500 herring for consumption by his household in 1300 when he stayed at Stirling Castle, and he showed his love of this fish still further by requesting 24 pasties of herring in return for the grant of a lease at Carlton. During the next century, Margaret Paston bought a horse load of herring for four shillings and sixpence, and complained to her husband that “that is all I can get at the moment.” Herring was dispersed far and wide from the town, and aside from brewing and the cloth and woollen trade, seems to have been the greatest source of income for the populace. Herring was sent in 1755 to such diverse places as Naples, Venice, Genoa, Ancona, Trieste, Bordeaux and of course throughout Britain also*3. Over the years there were tremendous ups and downs in the success or otherwise of the catch. Much of the town itself was devoted to fishing, and the ropewalks wereretained inside of the town wall until 1678. There was a lack of warehousing, and goods that could be traded in the open air were few. More perishable produce such as wool was moved straight from one ship to another, whilst herring was dealt with immediately upon landing.

During the Eighteenth Century

John Andrews whose house still stands upon the South Quay, was the most prominent fish tradesman in the 18th. Century, and owned 20 fish houses and six malt houses in 1741*4. The fishing then as always was unreliable. Some years had a glut of herring, and others were so poor that there was scarcely a living to be made. As an example, there were 7.5 million herring cured in 1760, and 9.2 millions in 1780. This contrasts with the glut in 1756 of nearly 73 millions, and 57.6 millions in 1773. At the end of that century the trade with Norwich in other consumables was dwindling, but there was a substantial Naval presence in the town due to the French wars, which caused a huge number of extra persons to be billeted in the town, and trade was developed supplying the personnel on shore and the naval vessels in the roads. The navy was stationed in the town from 1796-1811. Further business in regard of shipping was in terms of the construction of new vessels, by example there were 19 new vessels built in 1790, with a total tonnage of 2028, as many as 44 built in 1796.

In the Nineteenth Century

There were at least 7 dry docks in operation, 37 new vessels were built in 1805, and twelve new naval vessels were built between 1804 and 1808. Poor weather always had its effect, and it is noted that the wind was poor in 1886 and 1889 for instance. In 1880 it was a very bad year for fishing, 1886 was one of the “blackest on record”. In 1888 the season finished early- at the beginning of December, with the Scots boats having barely covered their costs. At that time it was said that the Scots used much finer nets than the English and sometimes flooded the market with undersized fish. Their boats were cheaper to build and cheaper to man than the local boats. In 1887 the number of vessels engaged in trawl fishing had declined from 606 in 1881, to 348. 1,500 less men were required that year, and then Yarmouth was the only trawl port with a separate trawl market. In 1900 there was a record herring catch of 28,450 lasts, equivalent to 3,049,000,000 herring! Pickled herring were sent to New York, Italy, Russia and Germany. Sixty one pickling plots were let on the South Denes (See Row 137 about the fish-house workers, also Blackfriars Road).

The Hazards of a Sailing Era

In the 19th. Century, The Yarmouth Roads were a rendezvous for the North Sea Fleet, protection being afforded from storms with the ships lying inland of the sand bars. Sailing ships had great problems in running to the north, as once free of the roads and passing Winterton, the wind if it came from a northerly direction, tended to blow a vessel back, such that it could not round Winterton Ness. Often, in attempting to run for the Lynn deeps, ships would founder on rocks off Cromer. Wooden ships, if beached during a high sea or in a gale would usually break their backs and become prey for the beachmen, ever watchful in these parts.The beachmen would observe along the coast with their telescopes, whilst perched high upon precarious looking watch-towers. In competition with them were the intrepid volunteer lifeboat crews and the Coast-guard, who had their impressive premises on the site which is now the “Oasis” on Marine Parade.The last company of beachmen to operate in Yarmouth was the Standard Company, which in around 1910 had incorporated what was left of the Young Company, and finished up as a pleasure boat operating company, with share-holders (see also under “Marine Parade”).

Trading on the fishwharf in about 1870

Commencing the Twentieth Century

“The fishing came into full swing with the October full moon and by then there would be some 800 Scotch drifters and 200 English drifters using the port. All the Scotch fishermen kept the Sabbath and remained in port until midnight, and frequently during the fishing one could cross the river by stepping from one tier of boats to another. The type of boat varied exceedingly, from a well equipped steam drifter to a smaller boat relying entirely upon sail. The steam drifter had two masts, and the hind mast always carried a sail to give her steerage. Many of the Scotch boats had a tall thick mast and relied upon a huge black triangular sail, which was often reinforced by an auxiliary engine. It was a wonderful sight upon a windy day, when catches were good, to see hundreds of boats making for harbour under sail or steam. In those days ships and gear were comparatively cheap; it was estimated that one Sunday there were 1,000 ships in the harbour at a total value of about three million pounds - £3,000 a boat on average.When the boats reached the herring grounds the way was more or less stopped, and the boat drifted with the tide. The crew then cast or shot their nets and they then drifted down the tide, and were kept in position by use of the boats windage (sail) or engines. As there were hundreds of boats in a very confined area it was a tricky business, so that a sudden or unexpected change of wind led to disaster with tangled nets. Most boats carried a crew of ten, and the Scotch boats were often belonging to and manned by one family. The nets were often more than a mile in length, when all shot out. Sometimes the herring struck the nets so heavily that they were grounded and lost. Sometimes a boat could not land all its full nets, and had to give part of its catch (nets and all) to a less fortunate neighbour. Those little boats were remarkably seaworthy and were very seldom lost. Members of a crew were occasionally washed overboard, but in at least one instance the next wave threw the man on board again, and he was then able to hold on" (edited extracts of Dr. Ley's Memoirs).

The Scots Girls

"On shore there was enormous activity. There was an influx of some five to six thousand Scotch fisher girls, who gutted, salted and boxed or barrelled the herring. They also worked in the smoke or curing houses. Local girls worked along side them, but were outnumbered. The girls even worked at night by the light of naphtha flares. Troughs full of silver fish were a wonderful sight, under the light of the naphtha, glistening in the troughs, the stalwart girls bare armed, black wet aprons spangled with scales, red weather worn comely faces crowned by multi-coloured scarves, with shuttling hands wielding gutting knives and casting the gutted fish into waiting barrels. Some 60 fish a minute were gutted by one girl. At the same time the fish were graded for quality and cast into separate barrels. Fingers were covered in bandages, cast off bandages were found on the ground months after the end of the fishing season. The girls were tough. In those days before the first war they were paid ten shillings a week for certain, and at the end of the fishing season so much on the barrel if they did well enough. To house all the Scots girls the poorer inhabitants of the town completely cleared two rooms, one to act as a living room with two boxes for seats and perhaps a table. The girls often then slept three in a bed. They paid very little for the lodgings, about three shillings and sixpence each. For that sum they received light and cooking facilities. Many houses did not have electricity before the first war. Rations for the girls comprised bread, soup, vegetables and fish". Dr. Ley says that many of the girls were well educated, as were the Scots fishermen, although some of the girls from the north and the Scottish Isles could only speak the Gaelic. "When not working the girls were often seen strolling about the town, sometimes singing, sometimes chatting amongst themselves, and constantly knitting. As well as the invasion of girls, there were the Scots coopers, carters and bakers, several hundred men in all. The Scots stayed in the town for three months, spending a large proportion of their earnings in the town, especially boosting the licenced trade. They also bought large presents to take home, which were lashed to the boats. Before the first war the town depended very largely upon the fishing industry for its living. Most of the fish was exported to Russia, but substantial amounts were bought by the curing houses throughout the town, and that way the industry continued throughout the winter, and into the spring, with the fish preserved in salting tanks. The fish sent to Russia was tightly packed into barrels with layers of salt. The Russian peasants apparently drank the brine as well as eating the fish, as they were starved of salt by a penal salt tax. The Russian buyers tested the quality of the herring by breaking a barrel and biting a piece out of the herrings back to sample it. No one was too fussy about hygiene. The fishermen themselves were remunerated on a share system, and the share of course depended on the season’s catch. If it was bad the boat’s crew could even end up in debt to the owner!”

Immediately following the first World War, the number of boats was 300, but another thousand or so joined in the season from Scotland. Nearly all the able bodied seamen had joined during that war the trawler section of the Royal Naval Reserve, and participated in drifter patrols, mine sweeping and anti submarine work. Sailing drifters became virtually obsolete at the end of that same war, replaced by steam drifters. The catch for 1919 was 453,458 crans, the cran containing 1000 fish. The annual catch was therefore around 400-500 million fish. The greatest catch in any one day was recorded in 1907, on October 23rd., when over 60,000 cran, or 60 million herring were landed at the fishwharf.

Several occupants of Lime Kiln Walk were fishermen, and many old fishermen who can describe the fishing as it was before the decline, are still alive. One such old fisherman not of Lime Kiln Walk, was Walter King, born in Winterton in 1906. His father, also named Walter, and his mother Lavinia (Hodds), both originated in Winterton; his story follows:

Under Attack

For a year or so they lived in Yarmouth on Alderson Road, and Walter King, at the age of 9, was passing St Peter's Church with two other boys, as the Zeppelin passed over that dropped bombs on St. Peter's Plain, and blew out the windows of the church. The boys just ran, and reached the market as the bombs fell. Later, during the same war, whilst standing upon the sand hills at Winterton, Walter saw the German Fleet that shelled Yarmouth, and demolished a house on Euston Road. He could see the guns flashing on the ships. At the very same moment, Dr. Ley was in his home opposite the Wellington Pier. It was the early morning of 4th. November 1914. At first light there was the thunder of guns, and the house shook. Ley realised that a Naval Battle was beginning, dressed with all haste, and made for the pier, which was only about 200 yards away. By the time he got there, the worst of the deafening noise had passed but there was still the flickering of guns on the horizon. When the firing had started there were some half dozen fishermen on the pier. At first they watched shells falling short in the sea, but as they got nearer, perhaps 600 hundred yards from the beach, one man said “I’m going in out of this” and bolted into the rather fragile bandstand nearby. The Germans were shelling the beach with 11 inch guns on battle cruisers.

The drifters were modified in the war to carry a six pounder gun mounted upon the bow, and with depth charges carried at the stern ready to be dropped from chutes. They had a hydrophone, were often equipped with a wireless set, and carried a crew of fishermen who had been trained for the service. They were dispatched to deal with “U” boats in the North Sea, and also in the Arctic, the White Sea, even in the Atlantic, Mediterranean, Agean and Adriatic Seas. In the Channel they joined the “Dover Patrol”, and roamed along the French Coast. Yarmouth itself was used as a submarine base during the First World War, and there was a Naval Air Station on the South Denes.

Walter King's father was skipper of his own boat, the "Ascendant", and young Walter started on it as cook in 1921. The vessel had a crew of ten men. Walter had first been educated in Winterton, and then briefly at the Northgate school; they moved to Yarmouth, because his father had shares in Bloomfield's company, but they left their house in the town due to the hostilities.Walter was the oldest child of Walter King and Lavinia (Hodds), both of Winterton. Other children were Rhoda, Charlie, May, Doris, Rosie, Ronnie, and Mary. Rhoda married another Winterton King. Walter acquired a share in the "Ocean Guide". This boat which was new in 1914, and launched at Oulton Broad, was called upon to sail as a patrol boat during the first war. There was a 12 pounder gun on the vessel, and the ship was stationed at Fleetwood.

Duties of a ship’s cook

The duties of cook were to coil the ropes on the ship as well as to prepare the food for the crew. There was a breakfast of herring; lunch was generally roast meat, or beef dumpling, or suet pudding, and tea was again fish. There was bread and margarine, and a kettle of a gallon or so of water was boiled up and simmered all day, full of tea and milk, which became incredibly stewed, and as black as tar. The meals on the trawler were prepared by the cook, but on a drifter the men made their own meals. Golden syrup was then a favourite to spread upon the bread.

Young Walter graduated to the engine room, then to the post of mate. He attended the School of Navigation on the South Quay, to obtain his Master's Ticket. In 1933 he went trawling from Fleetwood, and then returned as a skipper to Yarmouth.

The river crowded with boats.

picture by Stone, about 1925.

Casting the nets

The herring nets were "shot" out for some miles around the boat. The crew would work all night, some men taking it in turns to have a break, whilst others looked after the nets to stop them fouling up. The nets were drifted perhaps two miles ahead of the vessel, some 80 or 90 nets at a time. At one time they used "sceine" netting, which was laid out in a circle, the boat returning to its mooring, after which the net was hauled in again on the winch, alternatively, the net was set out in a triangle before returning to haul it in. When trawling, the nets were held on wires, and kept open by otter drawers*6, that are set up vertically, being held on a type of sled on the bottom which by action of the "door" in the water held the net firmly out astride of the ship. There were iron shoes on the bottom, and the upright door-like vane was at an angle so as to keep moving outwards whilst holding the net down on the bottom, although the depth might vary- up to perhaps 40 fathoms. The depth would be gauged with a hand-held lead weight on a rope, dropped over the side, and there were none of the modern aids to fishing or to fish finding. Drifters in and out of Yarmouth in the season would put into port with fish every day. Trawlers might be out for 12 days, but in the winter season they could be away for perhaps 24 weeks, and visit Iceland and Ireland and the Scottish Ports. Drifters were 87 to 90 feet in length. The "Lydia Eva" is rather longer than the norm for a steam drifter. There was always fierce competition between them and the Scots fishermen. They would often be trying to fish the same area, and would "fight" each other off for the best line of fish, and would sometimes get their nets tangled.

If the catch in the drifter was insufficient to land, then the herring would be salted in the hold of the boat, and they would fish another day without returning to port. Bags of salt were carried, and the fish kept loose in the hold, to be put by hand into the baskets in port, that held 1/4 cran each. (28 stone to the cran) The fish were not gutted on the boat. The girls were paid by the buyers to gut the fish on the fishwharf. Nearly all the girls were Scots. Not many Yarmouth girls worked on the fishwharf. The families in the rows made a room vacant to take the girls in. When not working on the fishwharf they would be knitting. They brought a trunk with them, with a supply of their wool, hand spun and dried.

Johnson’s and Boning’s both had shops that supplied the fishermen with clothing, and they also bought knitted garments from the Scots girls. The girls were so fast at gutting that the fishermen had a hard job to keep up when unloading the ship.The boats would return home for a break at the time of the Yarmouth races, and after about three weeks would then go away again fishing through until Christmas.

Wild weather out at sea.

When Bloomfield's started, Walter King snr. had a share in the boats. Prior to that he had been with "Wee" Green, who had a "G" on the funnel of his ships. In 1913 the "Ocean Harvest" was new, built at Beecham's yard in Yarmouth, but after that Walter went on the "Ocean Guide", in which he took ownership shares.The fishermen themselves had a share in the catch.

James Bloomfield was the son of a Liverpool Solicitor who came to Yarmouth in 1902 and joined the staff of Smith’s Dock Trust Company. Within thwo years he was their general manager, and by 1911 he was able to establish his own ship owning company by forming a group of share holders. There was a capital investment of $50,000, held in one pound shares. A number of vessels were acquired,the first being the “Ocean Gift”, and on 1st.may 1911 the company acquired the “Ocean Pride”, a vessel that had been built in Middlesborough, and which acquired the registration- YH172. One of Bloomfields concerns was that some owners and fishermen were using too fine a mesh, and he formed the herring fisheries protection association to help combat the problem in October 1912. The headquarters of the association was in Yarmouth.As Bloomfield acquired more vessels he took them on in shared ownership with the skipper, so that for instance the Ocean Souvenir was co-owned with Solomon Brown, Blomfield had the majority interest of 43 shares, and Brown had 21. Similarly the Ocean Reward was held in 43 shares by Bloomfields, and 21 by E.Green. This particular boat being requisitioned during the war for naval service, Bloomfields purchased it outright after the armistice. Bloomfield’s company owned 15 vessels in 1913. During the first world war the boats were not allowed to come into port during daylight hours which must have made trade extremely difficult. Inevitably the German and Russian Trade ceased during the war, and after it there were the coal strikes,when it was often impossible to fish due to lack of fuel. James Bloomfield died aged 54 on 4th.November1922. Subsequent to his death, the firm became part of the Macfisheries group,which was incorporated into Lever Bos. Ltd. In 1922. In 1929, Unilever merged with a Dutch Company the “Dutch Margarine Union”, and the whole was known as “Unilever”. In 1925 Bloomfield fleet included 25 trawlers and drifters*9.

In the photographs there is a boat BF 188, a Scots boat, for whom Bloomfield's were agents, and the ship then flew the Bloomfield’s flag. The tug, the "George Jewson", can be seen, which was used by the commissioners, for dredging, and to tow sailing barges in and out of the river. The "Rose Hilda", can be also be seen, and this was one of "Wee" Green's boats. Another tug was the "Tactful". In the picture of the skippers, "Mabby" Brown is in the centre, with hand on his shoulder, and Eddie George is also in the photo. The longshore boats worked close to shore for whatever they could catch. In another photo, Joe Haylett is fourth left at the back, Benny Reed was the gentlemanso unfortunately killed by an explosion on the lifeboat, and is seen first on the left at the front. Joe George is at the front, second from the right. Condor is at the back right, and Billy Moggons second from the right at the back.The tall lighthouse at Gorleston Harbour showed a red light, and was the leading light into the harbour, with the white light on the pier to the left, and another, green light to the right. The tall light in the centre was called "Long Tom". Walter remembered the old Naval Hospital situated beyond St. Nicholas, which housed Naval Lunatics. One man there was supposed to be gathering fallen leaves in a barrow, but he had it upside down so that he wouldn't have to fill it. Perhaps he wasn't so mad! Eventually the Herring just disappeared, and for no very definite reason, though presumably they had been overfished for years. There were no good sized shoals to be found. The fishing industry always had its ups and downs.

Another fisherman was William Skoyles of 53 Harley Road,(1871- 1937) who took the "Kyoma" when new from Richards yard at Lowestoft in 1914, this boat was owned by Moores of Yarmouth. William Skoyles also sailed on the "Girl Ena", and on the "Arthur H. Johnson". When not fishing he worked at Johnson's oilskin factory. Born at Yarmouth he married Patience Ward, and was the father of eight daughters and three sons. Patience's parents kept horses at one time at the bottom of the north-west tower, it is said. Married in 1889, they had Patience, born 1891, who married a cooper, Ethel, born 1893, who married Harry Butler of Manchester, in 1915. Walter George was born in 1896, and another daughter, Mary, died in 1963. Violet was born in 1900, and Doris in 1903 both at Sculcotes. Another child was born in 1905, who married a Trinity House diver, Keller. Agnes, the youngest girl (born 1913), married Walter Orton, a warehouseman at Johnson’s. Derek Skoyles, born 1928, grandson of William, married Myra Stone of Yarmouth in 1950 and had one son, Clive, (born 1950, twice married he has two children, Laura and Michael). Derek Skoyles first went to sea in 1946, on cargo ships as engineer, tramp ships going abroad mostly to Scandinavian ports in Norway, Denmark and Finland. Sometimes they went as far as Gibraltar, and Iceland. Later he went fishing out of Lowestoft on vessels including the "Trinidad", the "Tobago", and the "Granada".

Onboard Engineering

As ships engineer he worked shifts, four hours on and four hours off. Aside from maintaining the engine he would take his turns on watch, and look after all the machinery and electrics. Spare parts such as pistons and bearings were carried on board. There were two engineers but only one engine. Once down at the Faeroes, a cylinder head cracked, and on lifting this, it was found to be fitted on a block on which the water cooling it could not be shut off to any one cylinder in the normal way, and they were forced to limp back to Lowestoft with the head stopped up with rags in it to close the leak! The vessel was rolling, making working on it very difficult, so that the head could only safely be partially lifted. Another time, when fishing in the north sea, the forward trawl warp jumped out of the roller and jammed in solid. The trawl doors being on the bottom of the north sea at this point. They had to get the nut off from under thick layers of paint, knock the pin back, tie the roller up so that it couldn't drop, pull some slack off the winch to get the warp (wire) slack to get it back into the sheave. This was exceedingly difficult.

Preserving the fish at sea

The trawl doors pushed the net apart as the whole was pulled over the ocean floor. “Ticklers” were used in the mouth of the net- a huge chain. This chain disturbed the flatfish which bury themselves in the bottom- soles and plaice- and this method no doubt contributed to the over-fishing. Nevertheless, after the war, there was at first a glut of fish. On a trip to Aberdeen the boat would be away 18 days. On board would be a ton of ice in the fish hold, which bonded itself together. The youngest deck-hand had the job of chopping the ice up with an axe, ready for the mate to put onto the fish. The ice at Lowestoft came from the Lowestoft Ice Co., but ships now have their own refrigerators. In the old days the steady plodding engine did nothing to harm the fish, but the old fishermen could tell the difference - with a diesel engine the fish tend to bruise due to the vibrations. Down in the fish hold there were "pounds"- sections within the hold, the fish would be layered alternately with ice in each "pound" at a time. It was important to have all the fish properly covered, otherwise if one fish went off, the whole cargo was liable to be condemned on return to harbour.

When at sea, undersized fish were generally eaten on board. On the first day at sea there would of course be no fish, and the diet was bacon. The fish would be gutted at sea by the deck-hands. There were generally 10 men in the crew on these vessels, but on a longer voyage to the Faeroes the ship would carry 12. The usual crew comprised the skipper, the mate, the chief and second engineer, cook, and five deck-hands. The cook would bake fresh bread and rolls on board, milk was tinned. Vegetables were generally boiled potatoes, and cabbage or dried peas. Six of the crew slept at the stern, and the rest in the focsle. The skipper, the mate, and the chief engineer each had their own cabins. Fresh water was always a problem, and shaving was frowned upon. On one trip there was an airlock in the water tank and they ran out of fresh water. They had to resort to melting the ice down to make tea, but it was very impure.

This family owned a considerable number of boats over the years.

Henry Eastick, a boat owner, whose father had also been a ship-owner, was the father of H. F. Eastick, born 1861, who died 26th. Dec.1934. In the early days he had sailing vessels, the "Piscator", "Hearts Ease", "Holmes-dale", "Ebenezer", "Oceans Gift", and "Boy Harry". The first steam drifter that Eastick had was "Constance", which was also owned by his son H. J. Eastick. Beeching's Yard had built the Piscator, which had replaced a lugger of the same name. H. F. Eastick, and his son H. J. Eastick, split up. H. J. took over the ownership of "Constance", later H. F. Eastick had "H. F. E." built for his son, and the "Constance" was sold. H. J. Eastick then bought the sailing drifter "Bury Head", and moved his business to Gorleston. H. F. Eastick had three other sons- E. E. Eastick, who was killed in the first world war, C. V. Eastick, and G. W. Eastick. All these brothers worked with the fishing vessels, and became owners. At the end of the season when laid up, the Eastick fleet could be found at Fisherman's Quay, Gorleston.

H. F. Eastick showed the Prince of Wales his fishing boats when he came to open the Haven Bridge on 21 st. Oct. 1930. The prince went on board the East-Holme drifter.

Mrs. Rachel Eastick was the wife of H. F., daughter of James Johnson, another boat owner. She died aged over 100 yrs. C. H. J. Eastick, son of C. V. Eastick., still has the fish shop on the corner of Drudge Road and England's Lane. Another boat owner, Miss R. S. Eastick, was the younger daughter of H. F., and the registered owner of the sailing drifter "Refraction".

When H. J. Eastick separated from his father, setting up on his own in Gorleston, he kept a net store at the rear of Pier Plain. Another net store belonged to C. V. Eastick and his son C. H. J., at Fisk's opening, Gorleston. The latter is now Futter's betting office. H. F. Eastick, with his sons E. E., G. W., and C. V., and the latter's son C. H. J., sailed their boats from the Swanston Road net store, and in total employed some 60 staff, including ransackers, beatsters, and riggers. "Ransackers" were the men who checked the nets over for damage, whereas "beatsters" were women whose work was to repair the damaged nets.

The Prunier Trophy

The Prunier herring trophy was inaugurated on 20th. July 1936. All drifters, steam and motor powered who fished from Lowestoft and Great Yarmouth in the season, could enter the competition. The vessel landing the greatest number of crans of fresh herrings at one time, at either port, could retain the trophy for the year, also recieving a £25 cash prize. The entire victorious crew could then dine at Prunier's Restaurant, together with two days sight-seeing in London.

In the event that an English boat won first prize, then a Scottish boat was to receive the second, and conversely if a Scots boat won, then an English boat was to be awarded second place. The winning boat also received a weather vane intended be fixed to the fore or mizzen mast of the vessel. Simone Barnogaud-Prunier, the grand-daughter of Alfred Prunier, founder of a famous Paris Restaurant, called "Madam Prunier", had moved to London in 1934, opening a successful branch at 72 St.James' Street. This prize was dreamed up by one Warner Allen,who was, it is said, a wine expert. His idea was to promote and encourage the Herring Industry, which was then in need of just that.The trophy was onefashioned of Purbeck Marble.It appeared as a hand rising from the sea, holding a herring. The statuette was fashioned by Charles Sykes.Several years later, the winning skipper was also presented with a silver cigarette box, and the crew-members each were presented with a silver ash tray. 1966 was the last year that the Prunier Trophy was awarded having been missed out entirely in 1965. The vessel "Suffolk Warrior", that was built 1960 at Lowestoft by Richards shipbuilders Co.,had won in 1964,at which time the skipper was E. Fiske, and the catch was 276.5 cran.*7

Richard's shipyard

Samuel Richards, aged 24 yrs., left Penzance, in 1876, in possession of 25 golden sovereigns, his intention being to work his passage to Lowestoft, aboard a Yarmouth sailing drifter called the "Five sisters". The eldest of a large family, Sam had learned the trade of boat builder whilst apprentice to his father, Samuel Richards Snr., in the family yard. The “Five Sisters” was no.YH609, the owner being Mr. C. W.Baizey of Gorleston. At about the same time, a Samuel Hewitt from Barking in Essex, moved to Yarmouth to become founder of the great “Short Blue” fleet of fishing smacks, after starting as a smack's boy in 1863. Eventually he would own 50-60 of the old sailing trawlers, besides half a dozen liners, and some carrying cutters.

In 1887 there were no less than four fleets of fishing smacks operating from Yarmouth, employing some 3000 men and boys, a large proportion being on Hewitt's payroll. Yarmouth's History in ship building commenced at least by the 15 th. century, probably much earlier, as in 1290 so skilful were the local shipwrights, that on the proposed marriage of the then Prince of Wales, (Edward II), the port of Yarmouth was commanded to build for the bridegroom a beautiful ship.

Isaac Preston opened a yard in 1782 on South Quay, and built 153 ships there during the following 40 years. Preston was succeeded by his son, who launched a further 102 vessels between then and 1841. In 1818, it is also recorded "as many as 100 ships were under construction on the quay".

Richards took over Fellows concern in January 1970, at which time the yard and its accompanying dry docks were used by Everards, maintaining their coasters and repairing ships belonging to owners. Richards had alternative ideas, commencing an ambitious re-organisation scheme costing £250,000. Shortly after acquiring the yard, there was an order for three new trawlers, two of which were made at Yarmouth. When launched in October 1971, the "Ripley Queen" became the first new vessel to be built in Yarmouth since November 1965, and was followed by "Underley Queen", in April 1971, two months after the third of that fleet, "Bentley Queen", had been launched at Lowestoft. In May 1973, it was reported that 1/4 million pounds was to be spent on both yards, Lowestoft was to concentrate on building bigger vessels, whereas

vessels were to be built under cover at Yarmouth. The first vessel to leave the new slipway at Yarmouth was the 90 foot "Kinloch" on March 29 th. 1974. A tug which was built for J. P. Knight and Co., of Rochester. Two 96 foot tugs, the "Alison Howard" and the "Lady Howard II", were built at Great Yarmouth in 1972-73, for John Howard and Co. Ltd., and registered in Bermuda. October 1973 saw the launch in Great Yarmouth of the 105 foot tug Ralph Cross, for the Tees Towing Co. A 1.5 million pound order was taken for two oil rig supply vessels for Offshore Marine of Great Yarmouth, a subsidiary of the Cunard Line. The latter order followed repair work on earlier similar vessels owned by the same company.The managers, foremen and office staff at the Yarmouth yard in 1976 were-

S. Taylor, J. Dinsdale, J. Southgate, I. Gook, M. Leeds, C.E. Clarke, R. Hughes, D. Boulton, T. Paterson, K. Coleman, L. Cox, T. Bridge, R. Bathgate, and G. Flint.*8

The Demise of the Fishing Industry

It appears that there were a number of factors conspiring together to bring about the complete and sudden end to this trade that had existed for more than a thousand years with scarcely an interuption. The fish were plentiful enough immediately following the second war. Many of the vessels did not survive the war, but the fish certainly did, and there was a glut initially. Likely the men did not much wish to carry on this hard existence on low wages, whilst new industries came to the town such as Birds Eye, Erie Resistor, and Hartman Fibre that attracted them away. Later, when there was a crisis in fish stocks, there was a need for investment in new larger vessels, which could not then afford to stand idle in a poor year (of which there had been plenty over the centuries). Economic necessity is always the downfall of trade in such circumstances. The new opportunities offered by the oil trade to such vessels, inevitably meant their conversion to such work, and they then were never to be redeployed. Many youngsters such as John Crane, (see South Quay) were able to seek other employment, and did not need to suffer in the fishing industry in the way that their fathers had.

There was a new standard of living in postwar Britain, and of course the newly created welfare state enabled men to refuse poorly paid work more easily. Going to sea in small ships for hard labour and low wages had lost any attraction. Now much better money was at hand working for the American sponsored oil and gas industry. Who under such circumstances would do otherwise? Before the war, men such as Sutton had declined to invest in machinery, since labour was cheaper. After the war, the investment in fishing became precarious, and simultaneously much greater, since the size and cost of a single vessel was vastly increased. The house-wife after the war was also more discerning, or at least had lost the taste for kippers, and other fish became much more widely sold. All these various factors came together at the same time in the early 1960's, and inevitably caused the death of the industry in Yarmouth. Paradoxically, if the industry had been much smaller, it may well have been less affected.

References:

*3 J.W. De Caux,The Herring and the Herring Fishery, p. 103.

*4 J.D. Murphy, “The Town and Trade of Gt. Yarmouth” 1740-1850, 1979, unpublished thesis at UEA.

*5, *7, “Herring Heydays”, by K. W. Kent.

*6 Called a drawer, sometimes door, sometimes an Otter board, but all the same thing.

*8 Ref. "The First Hundred Years, the story of Richards Ship-builders", by Charles Goodey, 1976.

*9 “The Ocean Fleet of Yarmouth” by L.W.Hawkins, 1983.

Also see-

“Reminiscences of a general Practitioner” by Leonard Ley, unpublished.

“The Yarmouth Herring Industry 1880-1960" by Mary Innes Fewster, unpublished UEA thesis, 1985.

“Herring nets and Beatsters”, C.Green, Norfolk Arch. vol 34, 1969

“Yarmouth Herring and Holiday Boom Town”, in “John Bull”, Aug.15th. 1953

Articles in Industrial Arch. Soc. Journal, 1972, 1981, by C.Lewis.

“The winners of the Prunier Trophy”, East Anglian Magasine, vol. 38, sept. 1979.

“The Herring and History”, History Today, vol.II, no.10, Oct. 1952.

Woolcombe J., “Why is the Norfolk Herring Fleet Fading Out?” Norfolk County Annual, 1968

“Yarmouth is an Ancient Town”, A.A.Hedges, 1959.