Below is the entire document as an HTML page, this allows internet searching, but to read the document itself, as originally set out, you may prefer to open it as a pdf. If so then email me for the file mark.rumble@freeuk.com

John Fall

2005 Technical Data

This volume was written using a WordPerfect 10 word processor The body of the text is in 12 point Times New Roman font Most quotations are in Lapidiary 333 BT 14 point font

Images were either scanned with a Cannon D1250 U2F scanner or obtained from a Nikon D 70 digital camera. They w ere processed with the Adobe Ph otoshop Elements image editing program

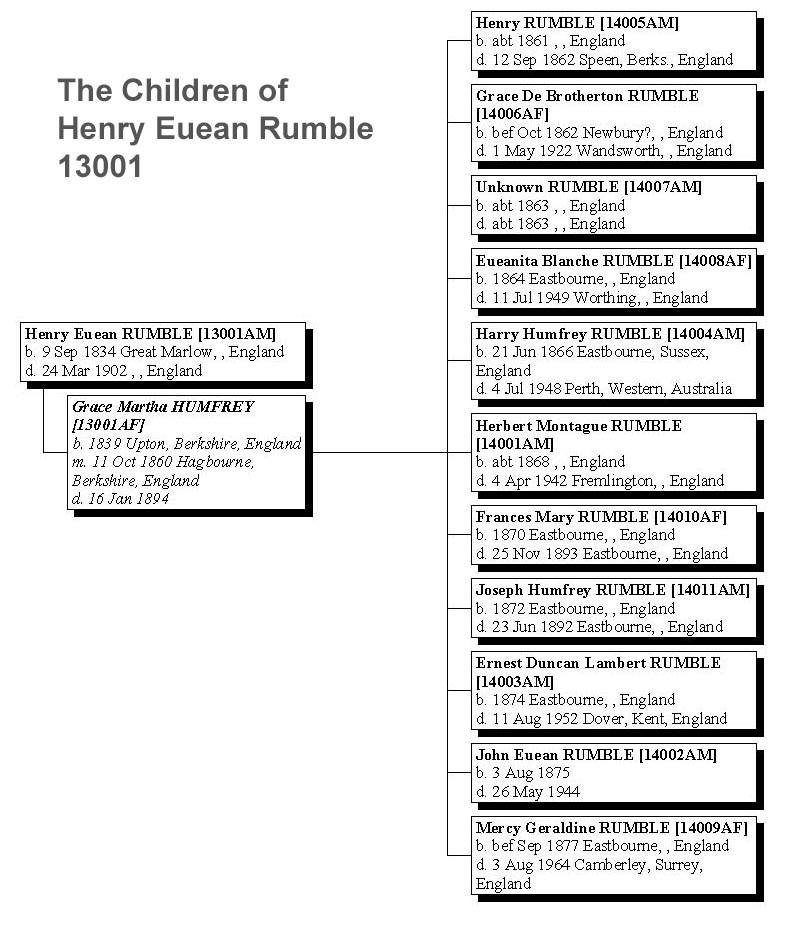

The Family Tree charts were generated as PDF files from the Personal Ancestral File 5.2 genealogical program of the Church of Latter Day Saints using the Personal Ancestral File Companion 5.1 program and were converted to JPEG image form at for inclusion in the text.

The final text was converted to PDF format and processed with the Adobe Acrobat 7.0 program, and stored on a compact disk, from which it was printed.

© Copy right 2005, John Fall 29 Paterson Gardens, Winthrop, Western Australia

Much of the material for this volume was drawn from two previous volumes that I wrote some time ago:

The Rumble Family Register, 1994 The Pot of Gold - The Autobiography of John Fall, 1998

Other major sources for my Chinese ancestry have been:

Guy Duncan: The Lives of John Hochee and John Fullerton Elphinstone, 2003 Peter Morris Jones: Family History, 2000

Both Guy and Peter are my third cousins.

Other members within the family who have assisted me are my second cousin Henry Knight and his daughter, Alexandra.

Andrew Williams - my second cousin removed by one generation was involved in discovering some family members, as outlined at the beginning of the book.

Within the Rumble family I was assisted by Mark Rumble and Michael Rumble and by Joyce, Joseph and Frances Rumble. Their relationship to me is shown in the chart on page 85.

Brenda Rohl, my first cousin removed by one generation, made a substantial research contribution when I was collecting material for the Rumble Family Register

I am also indebted to the Long Buckby Local History Society - and especially to Phil Davis - for early maps and photographs of Long Buckby village and for general background. This helped me enormously with putting together a more complete outline of the life of George Fall, my father’s father.

As always, my wife Kay has been of constant help in checking and proof-reading the material.

Introduction ......................................................... 1

My Ancestral tree to great-great-grandparents ........................... 2

Andy Williams and the ‘Four Generations’ photograph .................... 5

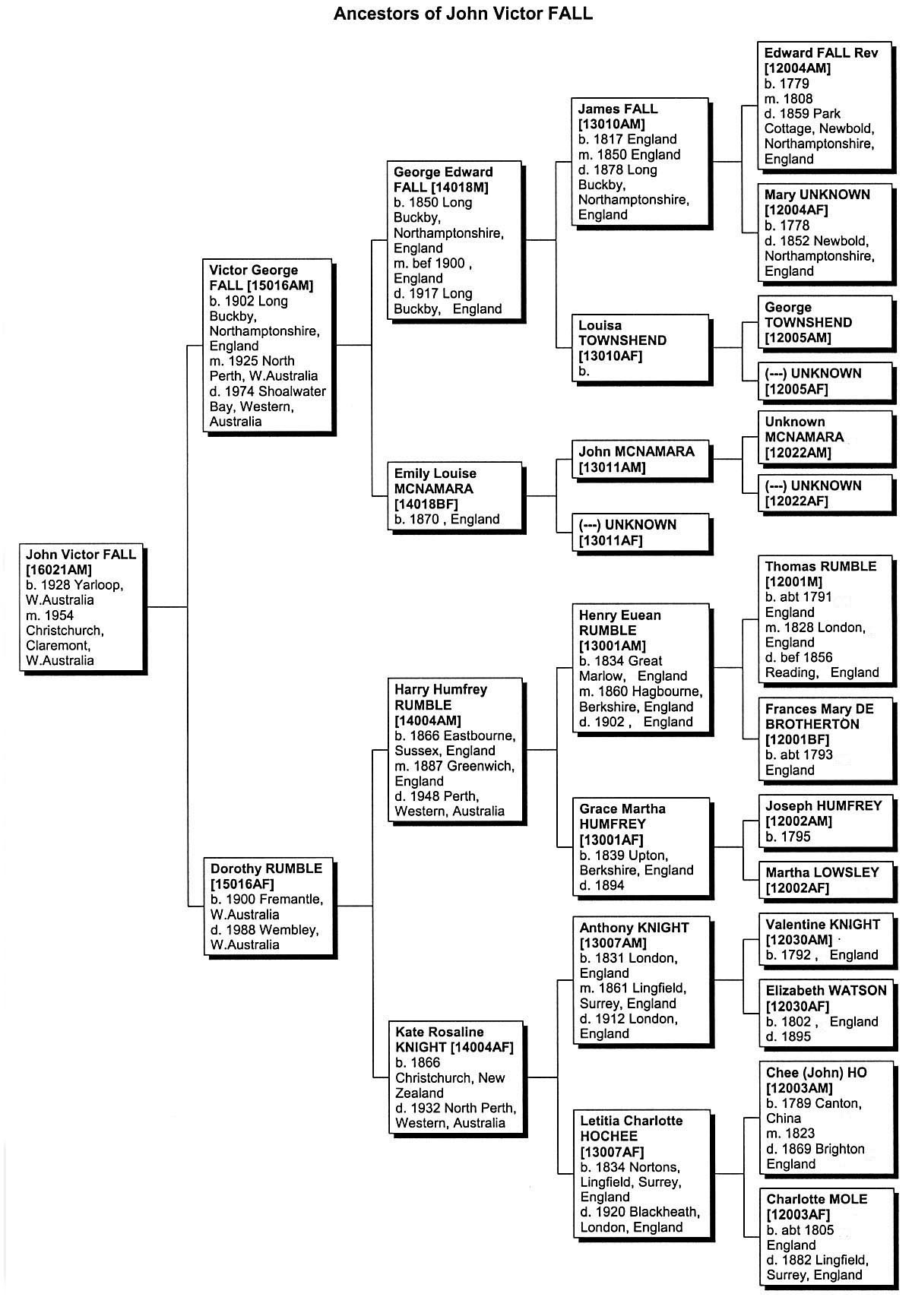

Part of the Hochee, Knight & Rumble Family Trees ...................... 6

The Background history of the Knights .................................... 7

My descendancy from Valentine Knight 10009 born 1722 ................. 9

The Valentine Knight burglary & Old Bailey Trial ................... 11

The second and third Valentine Knights ............................... 14

Memoir of Valentine Knight [12030] .............................. 15

His homes in later life ................................... 18

His family tree (his children) .............................. 20

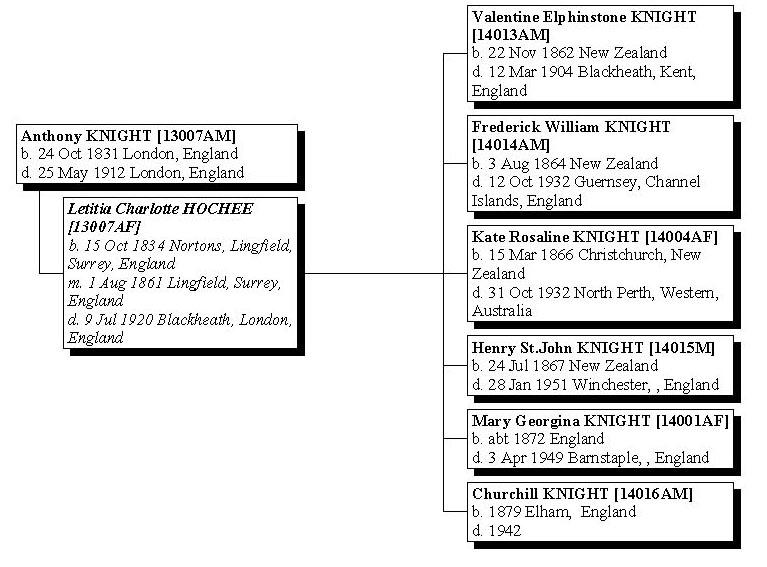

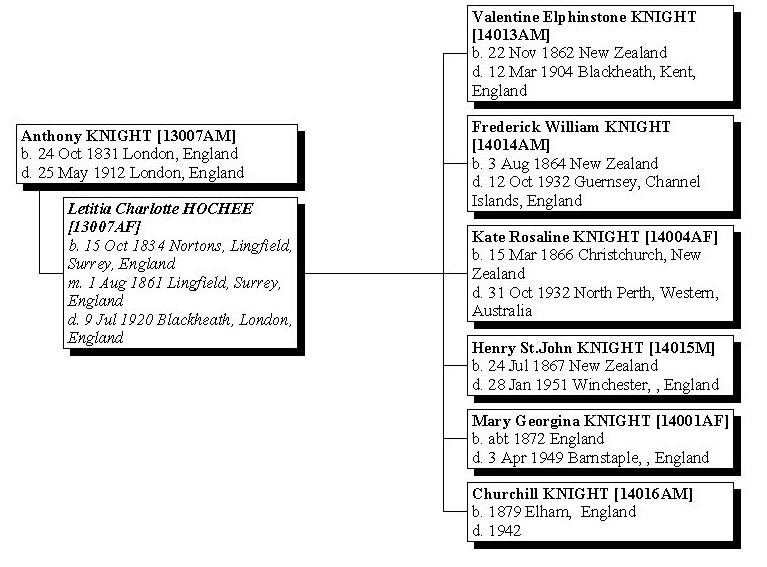

The Family of Anthony Knight [13007] .................................. 22

His children: Family tree ........................................... 22

The first search for Ho Chee [12003] .................................... 23

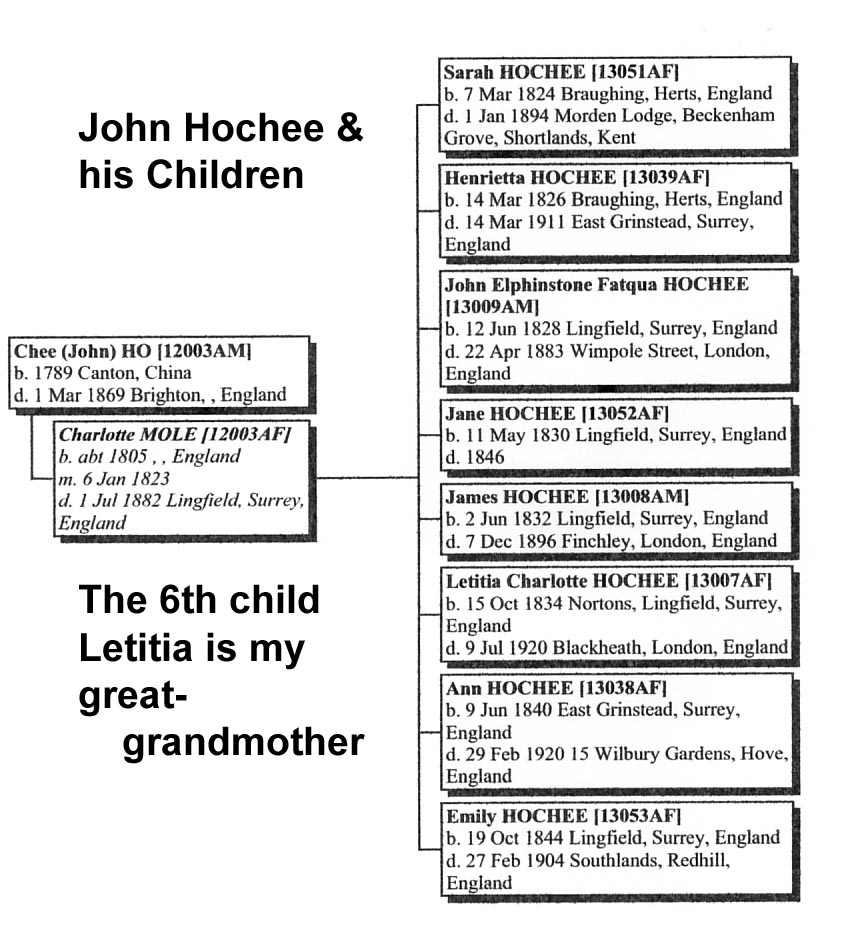

Hochee and his children: Family tree ................................. 25

Alexandra Knight’s history of Ho Chee ............................... 27

Hochee photo album .............................................. 32

Hochee Almshouses .............................................. 37

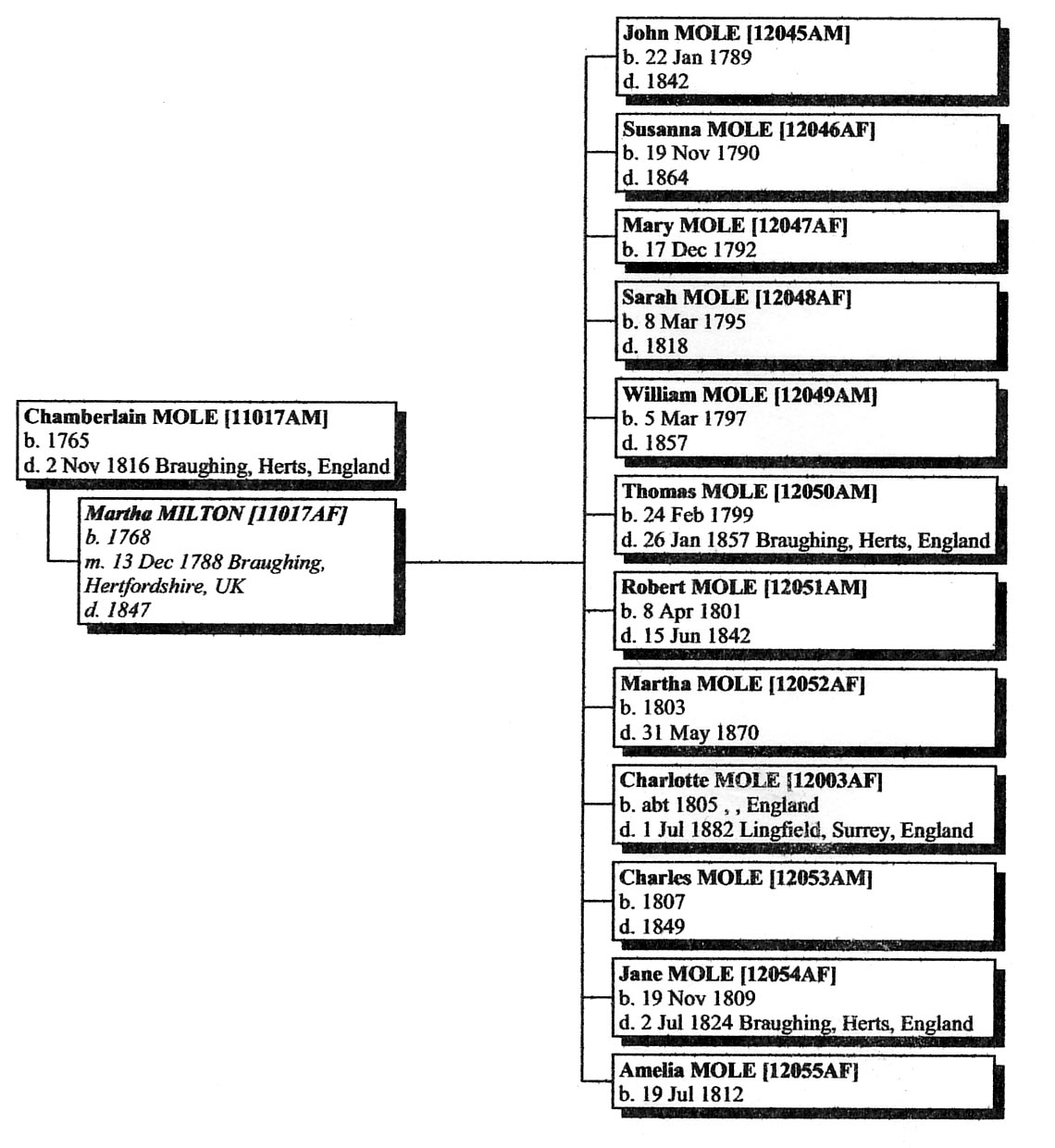

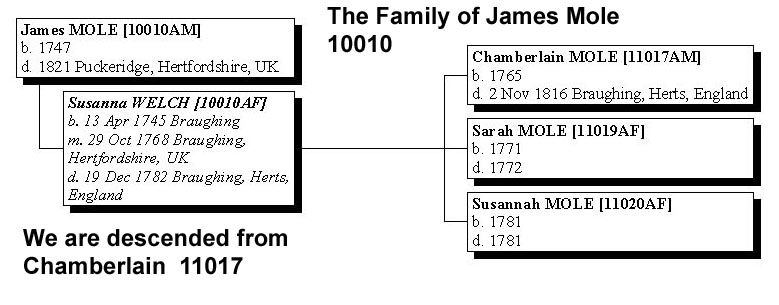

Ancestors of Charlotte Mole [12003] ................................. 40

Charlotte Mole’s background .................................... 41

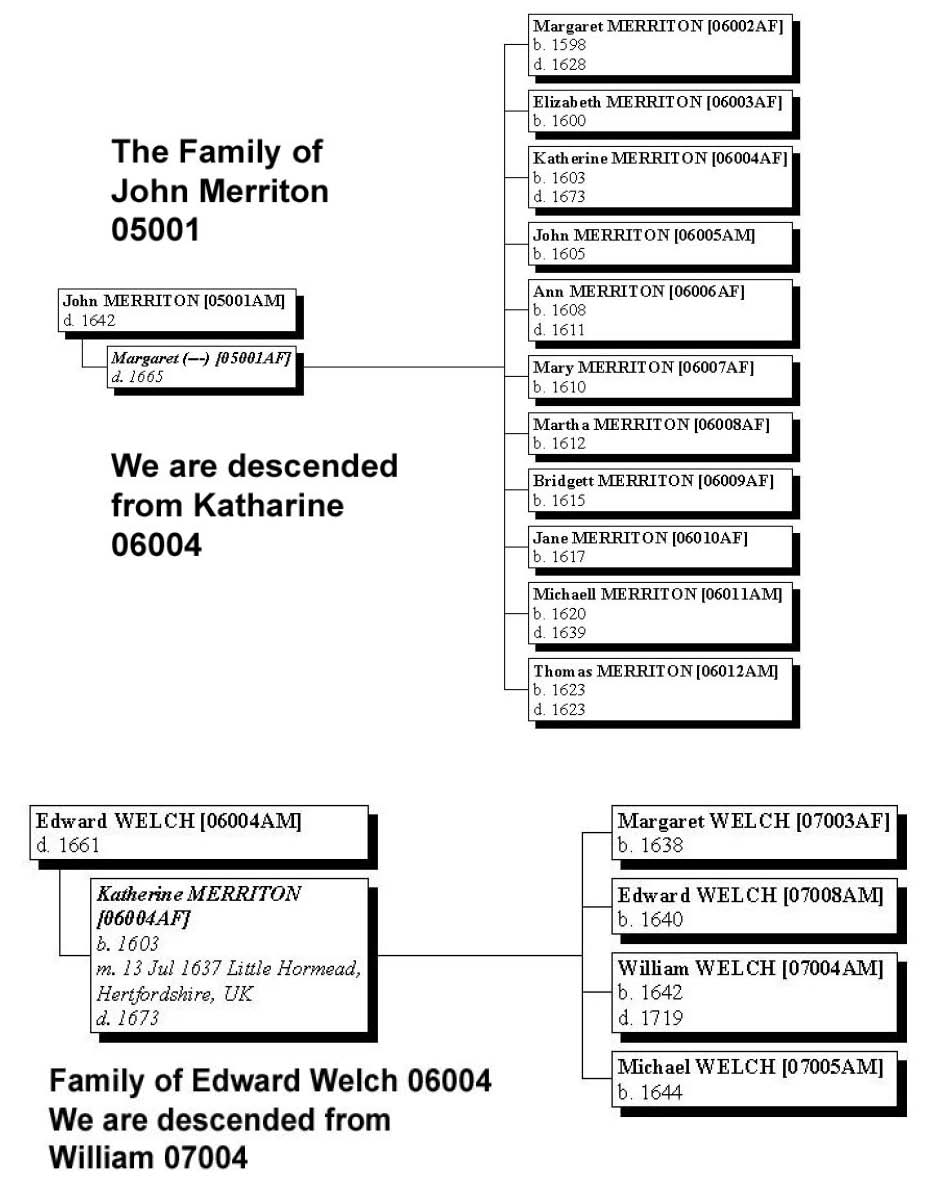

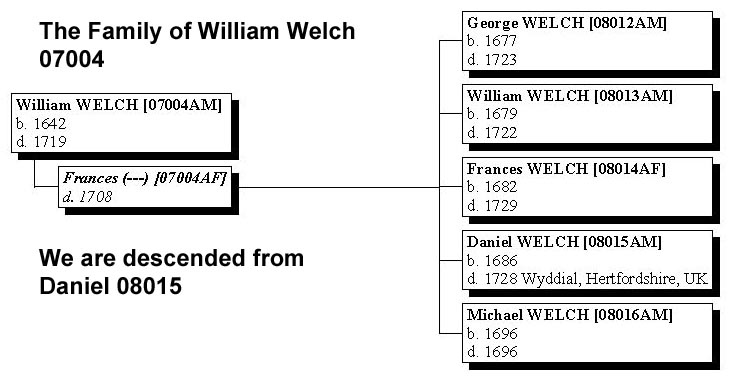

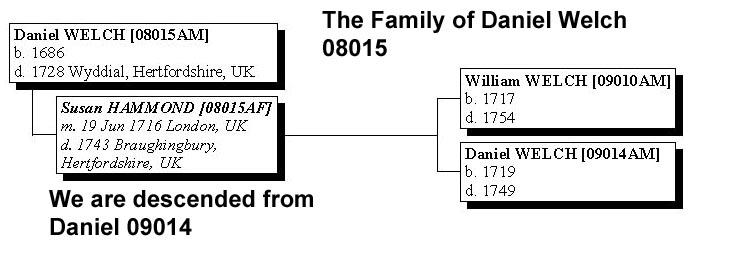

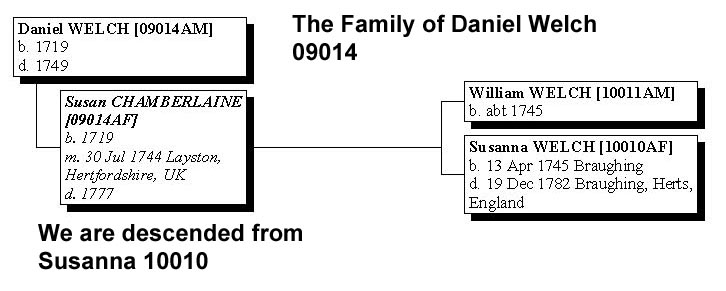

The Welch family ...................................... 42

Family charts .................................... 44

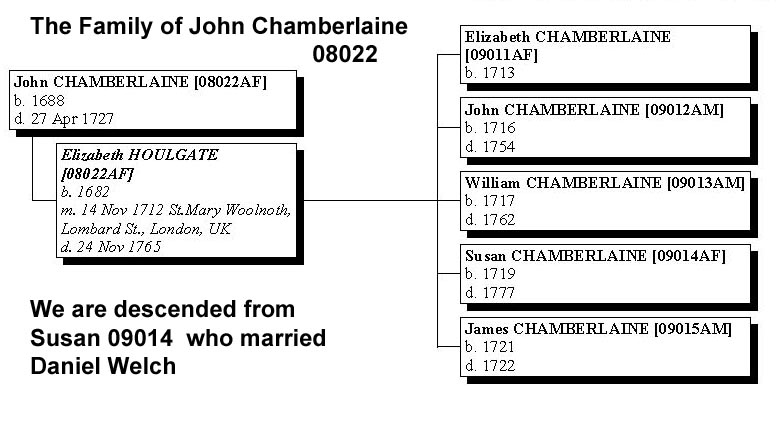

The Chamberlaine family ................................. 47

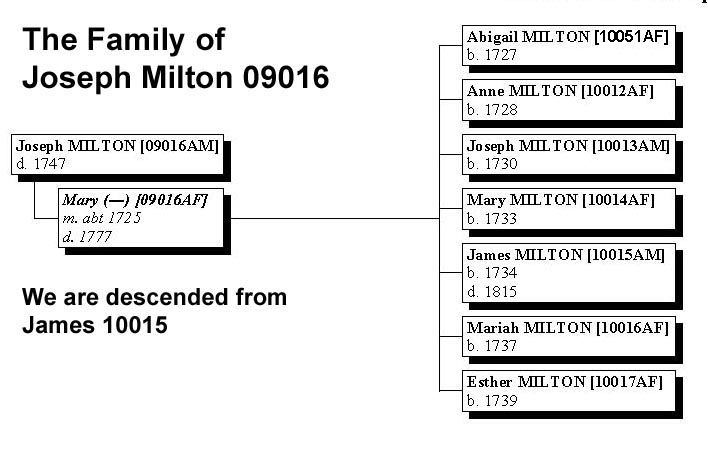

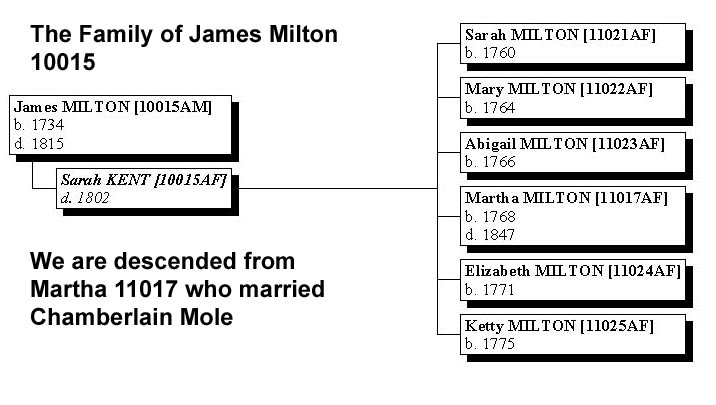

The Milton family ...................................... 49

Charlotte Mole’s life ........................................... 50

Third cousin Guy Duncan is discovered .................................. 51

The second search for Ho Chee ...................................... 53

Ho Chee’s origins in China ...................................... 56

The search for Ho Chee’s arrival in Britain ......................... 58

Ho Chee in Braughing and Lingfield .............................. 61

John Hochee’s later life ......................................... 64

The last days of John Hochee .................................... 65

curious comment on Hochee ................................... 66

Charlotte Hochee and the almshouses.............................. 67

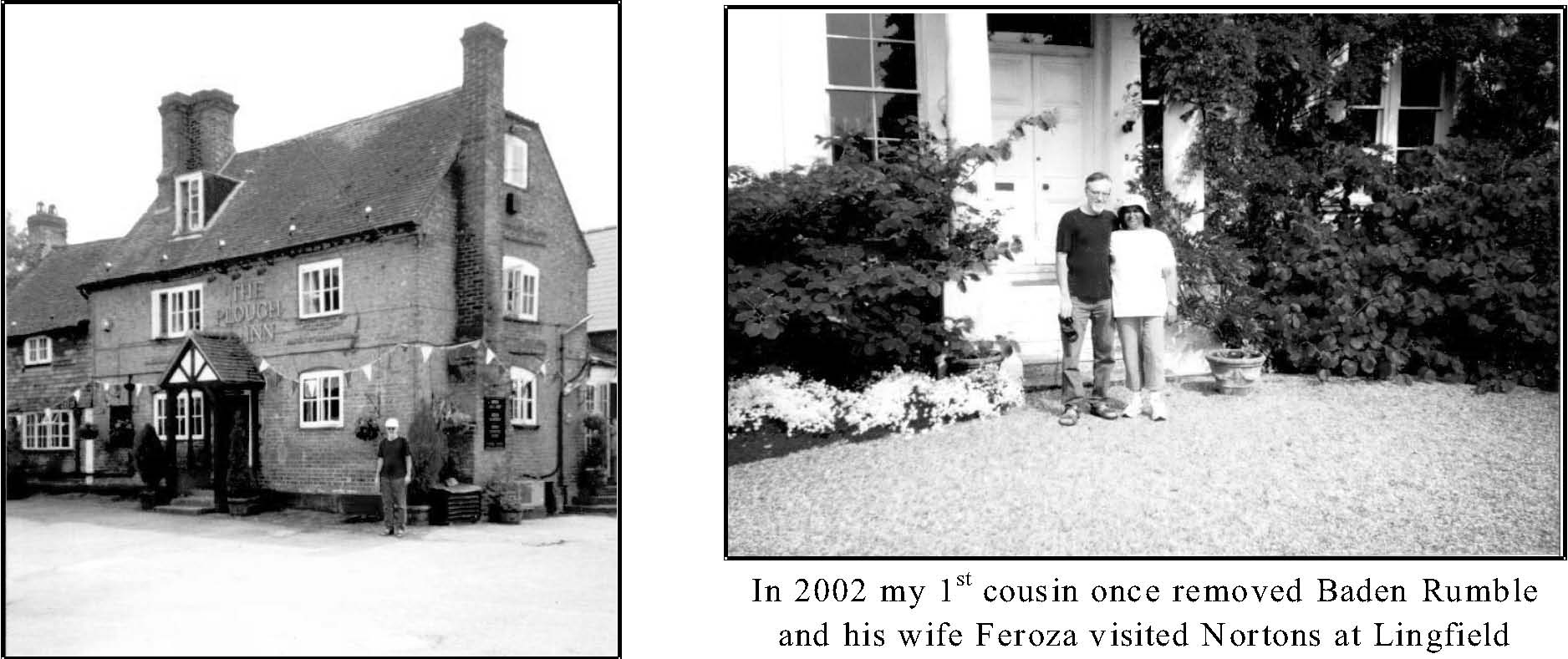

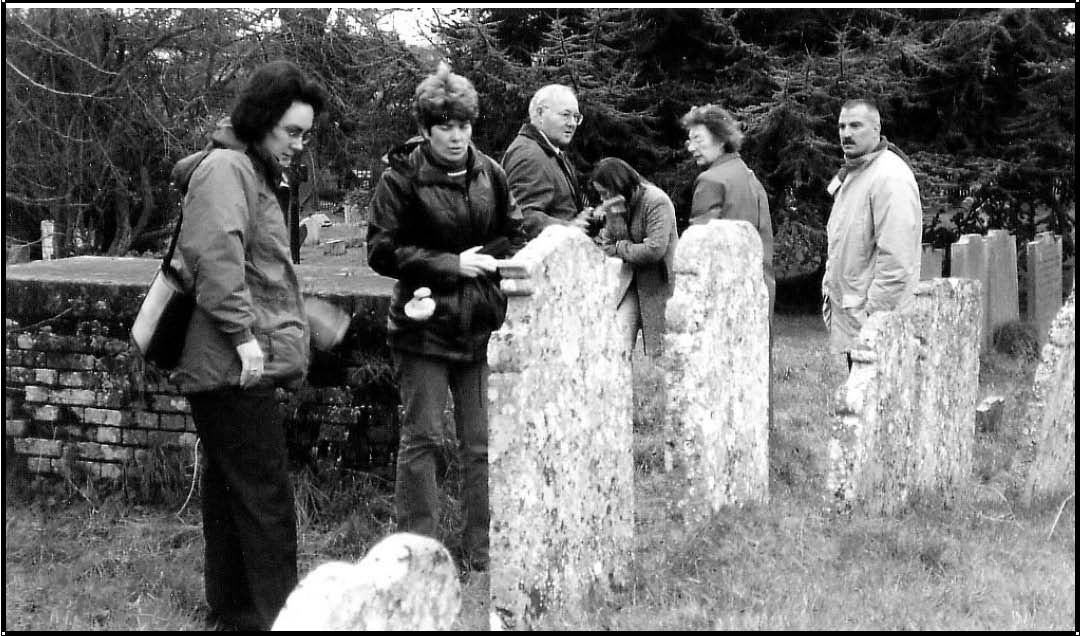

Recent family pilgrimages to Lingfield ................................ 68

The launching of Guy Duncan’s book on Hochee & Elphinstone ........... 69

The children of John and Charlotte Hochee ............................ 70

Anthony Knight and his wife Letitia Hochee .............................. 72

The children of Anthony and Letitia .................................. 82

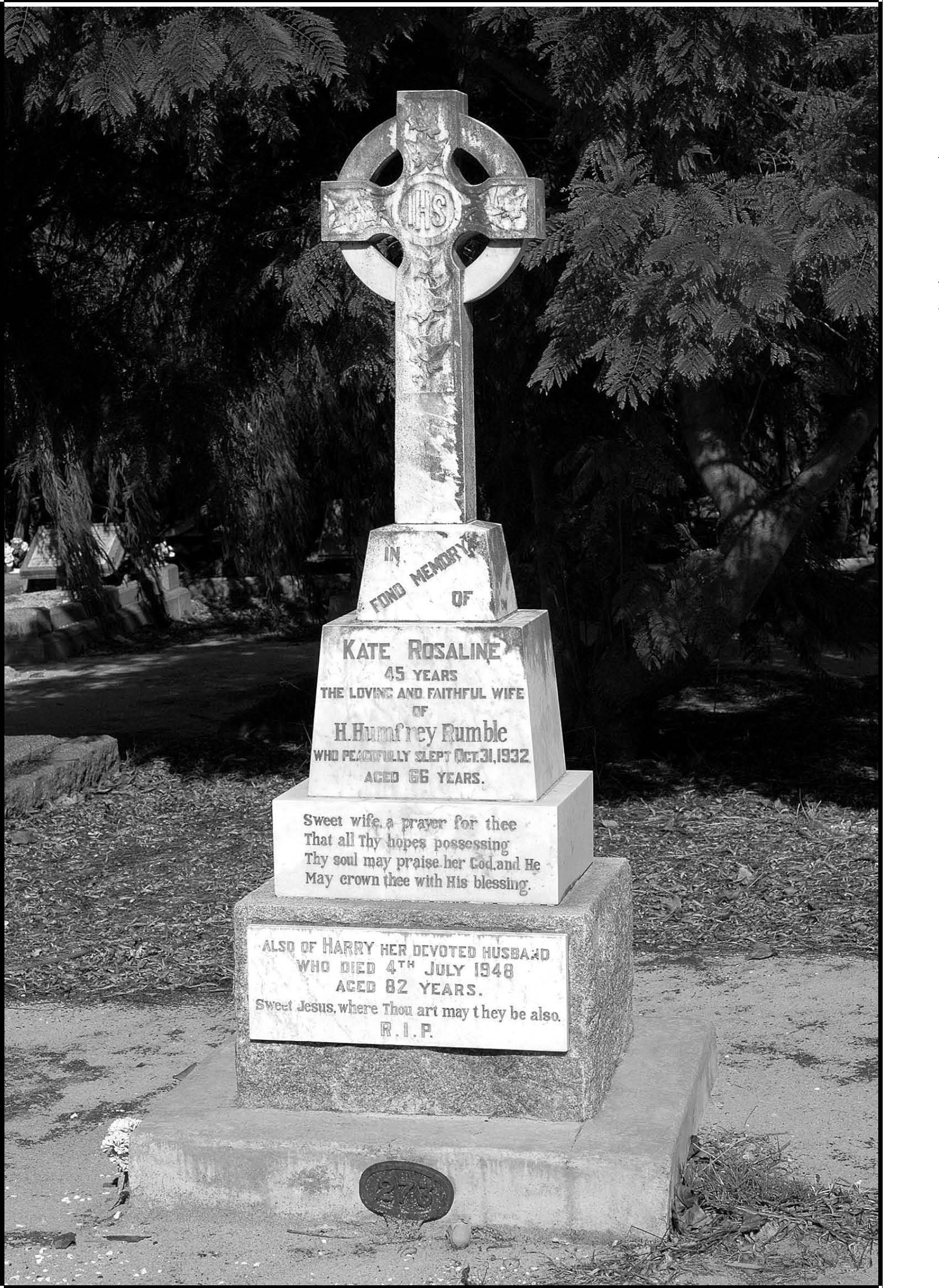

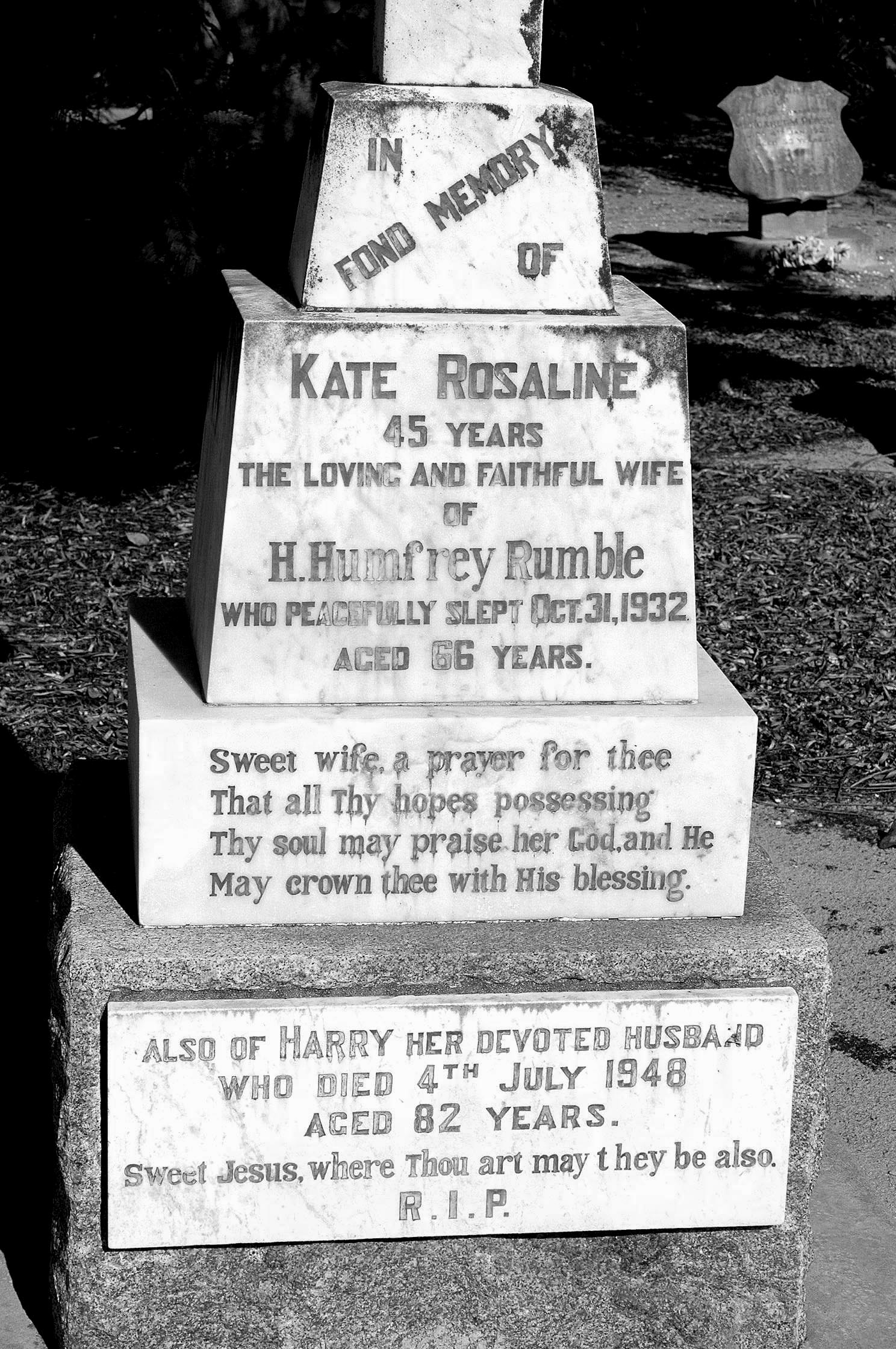

Kate Rosaline Knight and Harry Humfrey Rumble .......................... 85

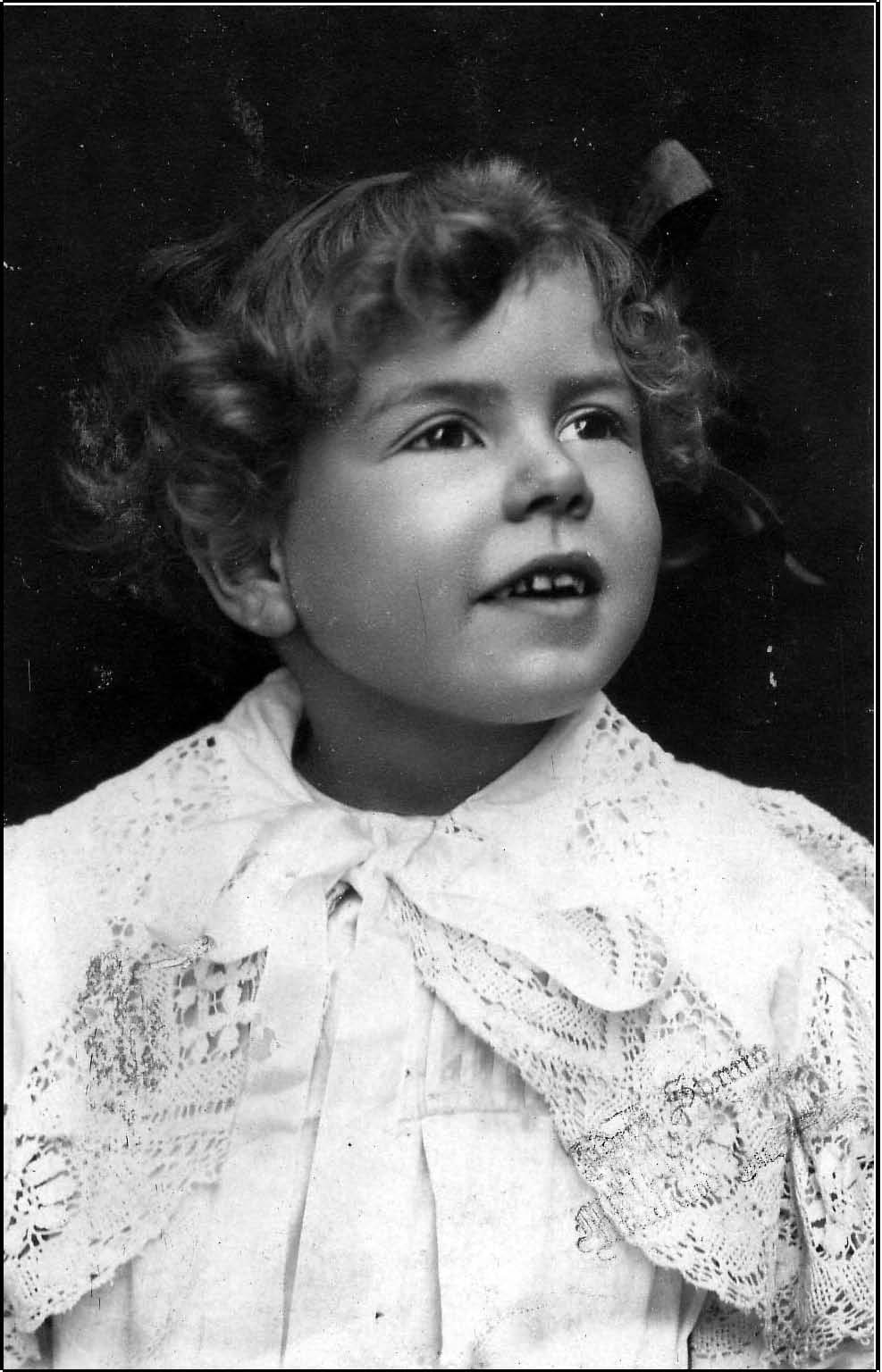

Kate Knight’s life as a child ........................................ 86

Marriage .................................................... 88

Harry Humfrey Rumble his ancestry ..................................................... 90

The Humfrey background .......................................... 91

: 4 generation family tree .................... 92

Thomas Humfrey 06001 ........................................ 93

: 4 generation family tree .................... 96

: 3 generation family tree ..................... 97

The children of Joseph Humfrey ........................... 98

Grace Humfrey 13001 ............................................ 100

The de Brotherton Ancestry .................................... 100

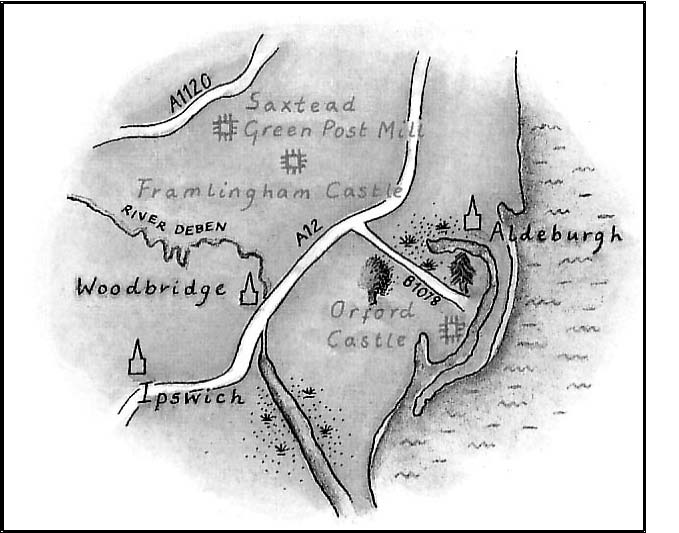

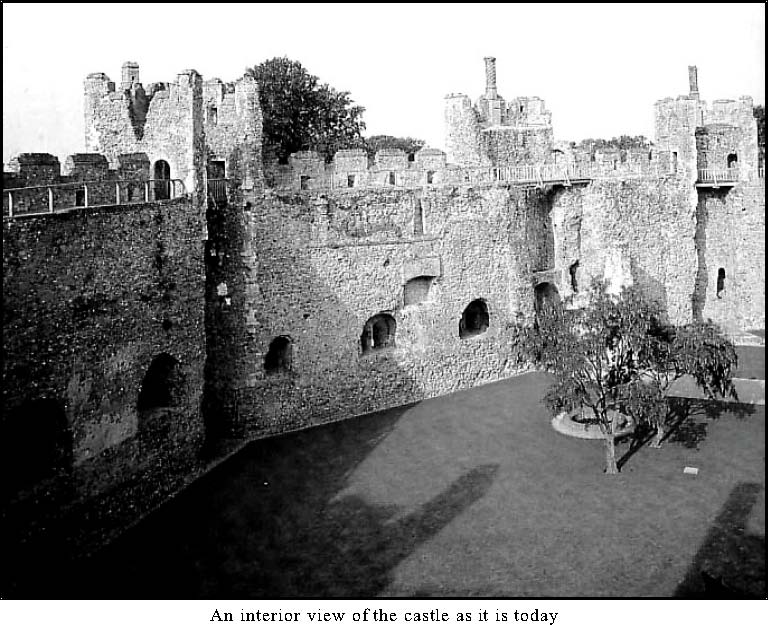

Framlingham Castle .................................... 102

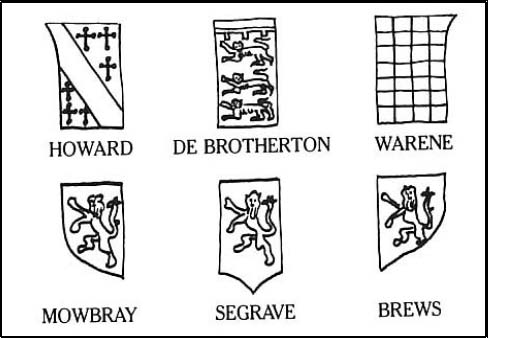

De Brotherton coat of arms .............................. 105

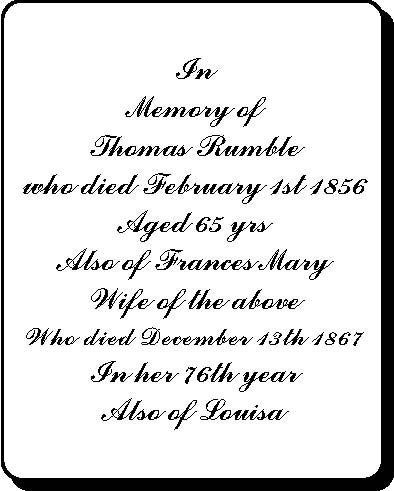

The Rumble Ancestry Thomas Rumble 12001 Descendancy chart for 3 generations ....................... 106

His life .............................................. 107

Frances Mary de Broltherton.................................... 109

The children of Thomas and Frances ....................... 110

Henry Euean Rumble 13001 .................................... 111

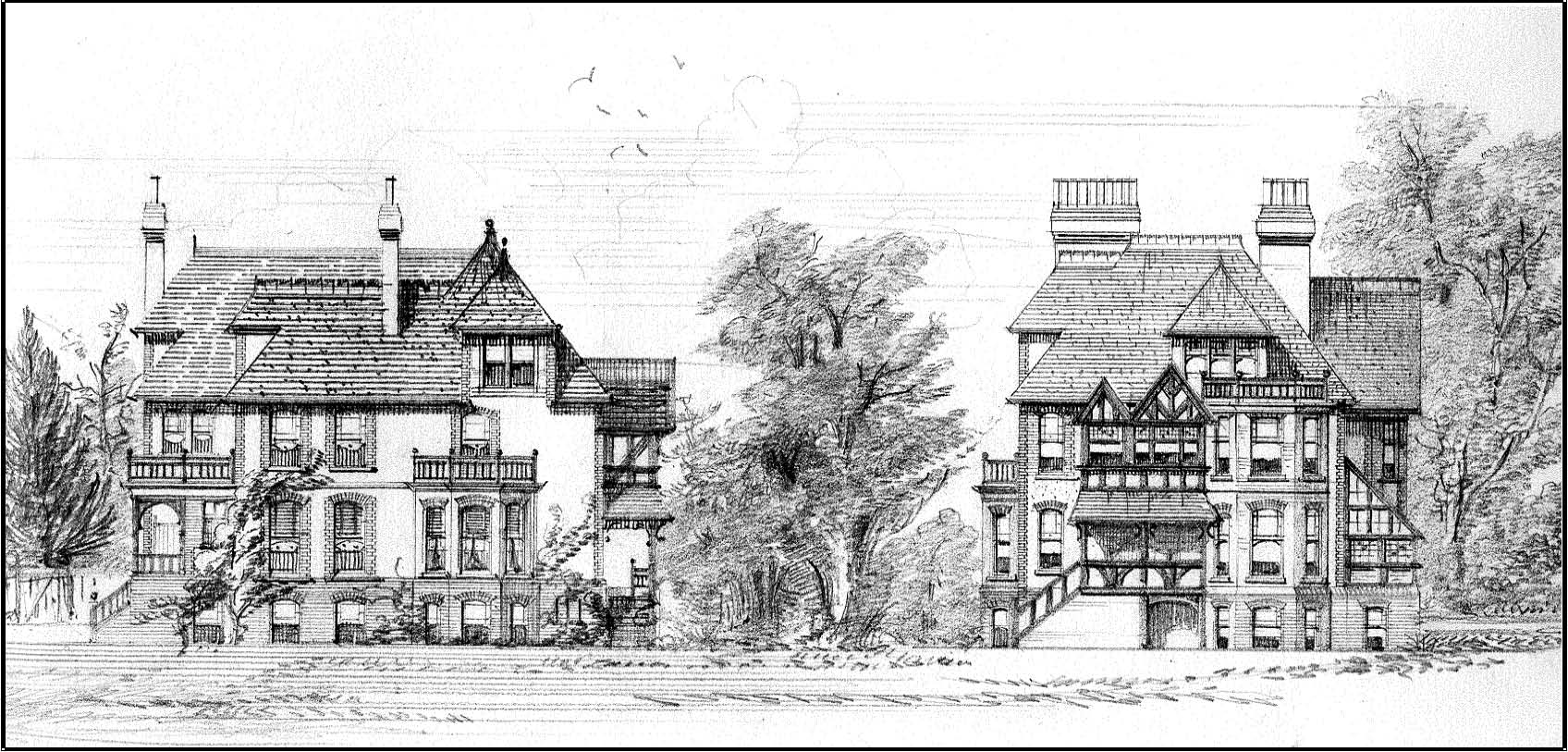

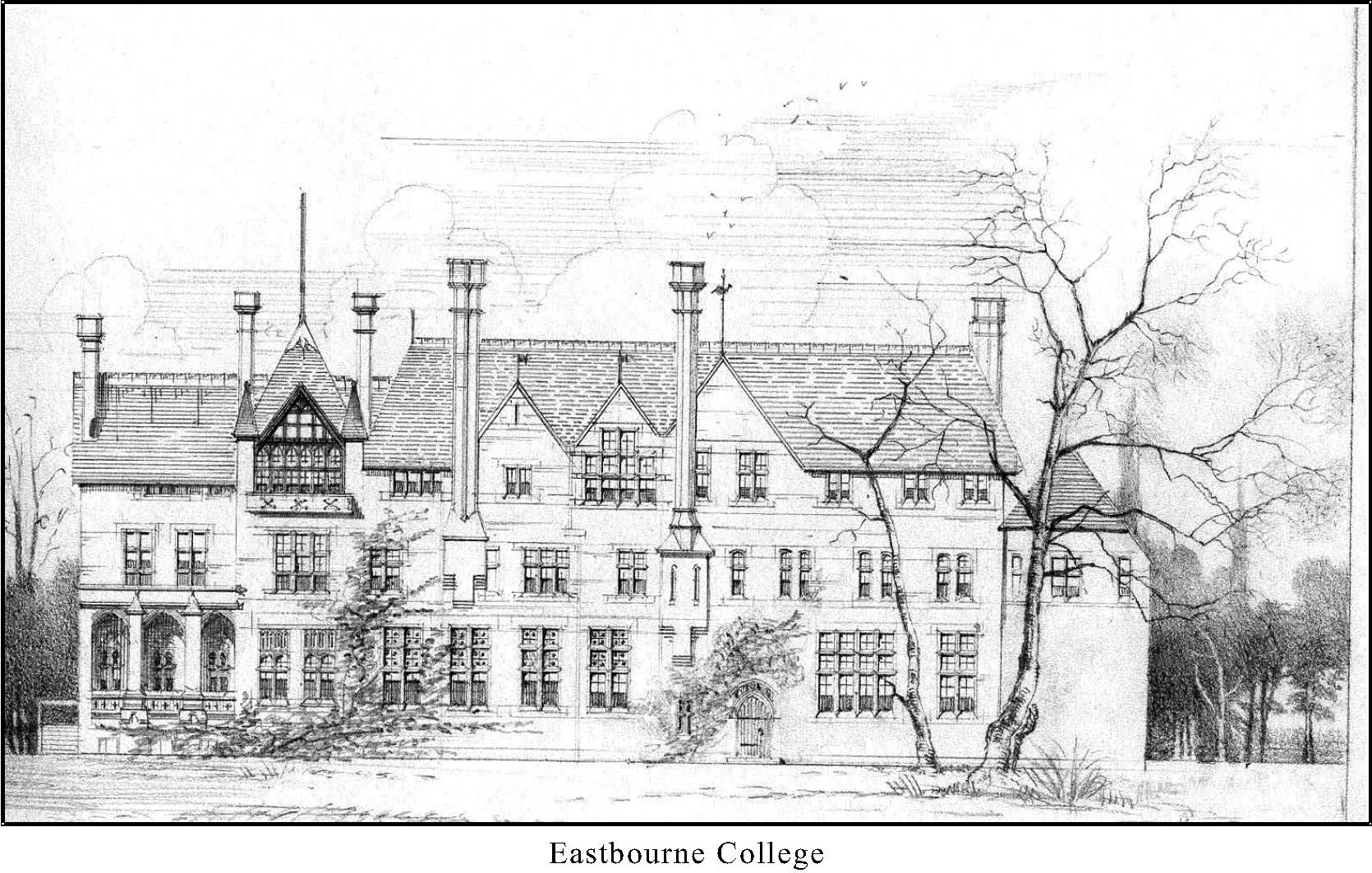

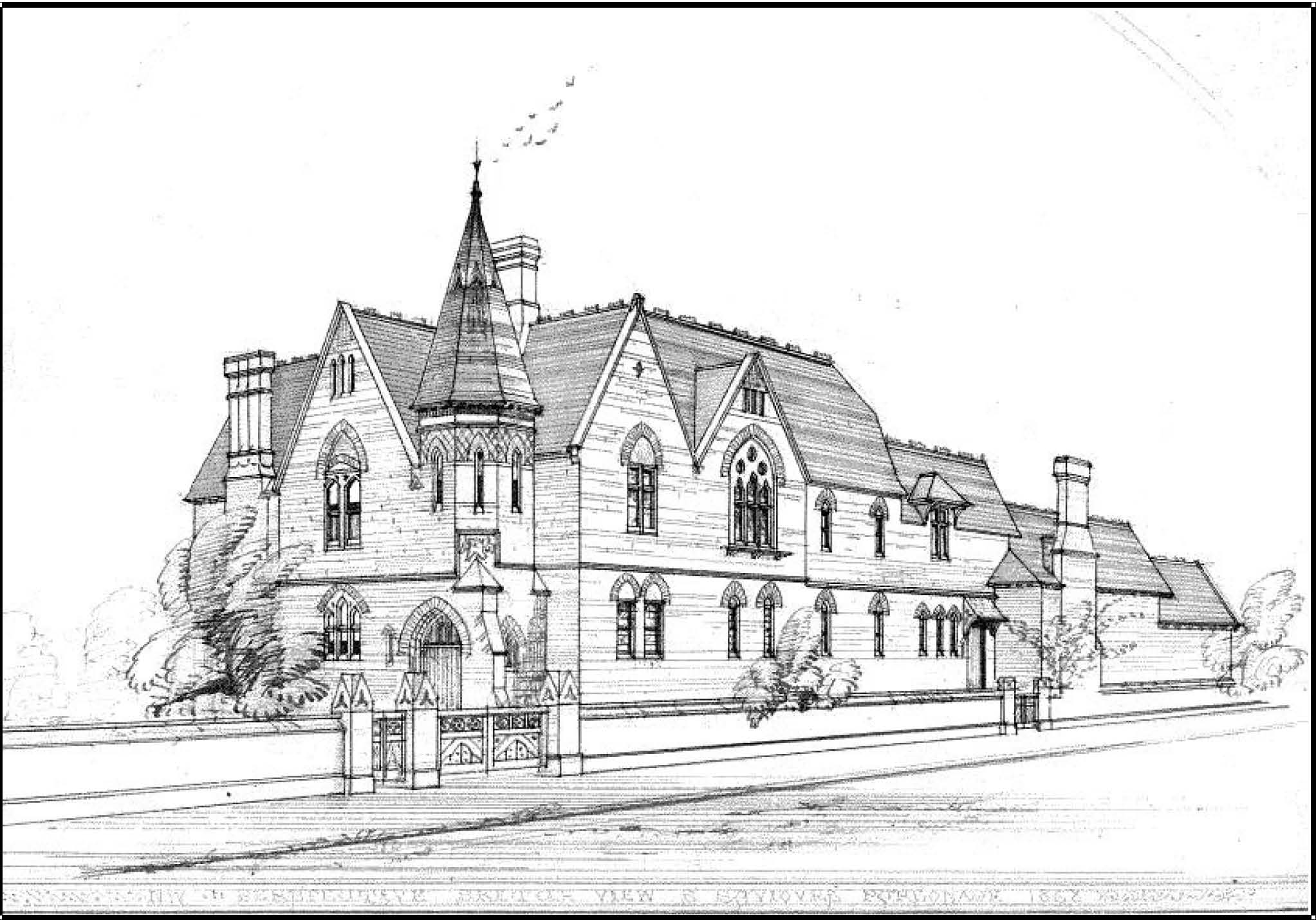

Architectural drawings .................................. 113

His children .......................................... 116

Ernest Rumble & his drawings............................ 118

Joseph Rumble’s drawings............................... 120

Harry Humfrey Rumble & Kate Rosaline Knight 14004..................... 122

The Family Quarrels ............................................. 122

Migration to Sydney ............................................. 123

The move to Western Australia ..................................... 124

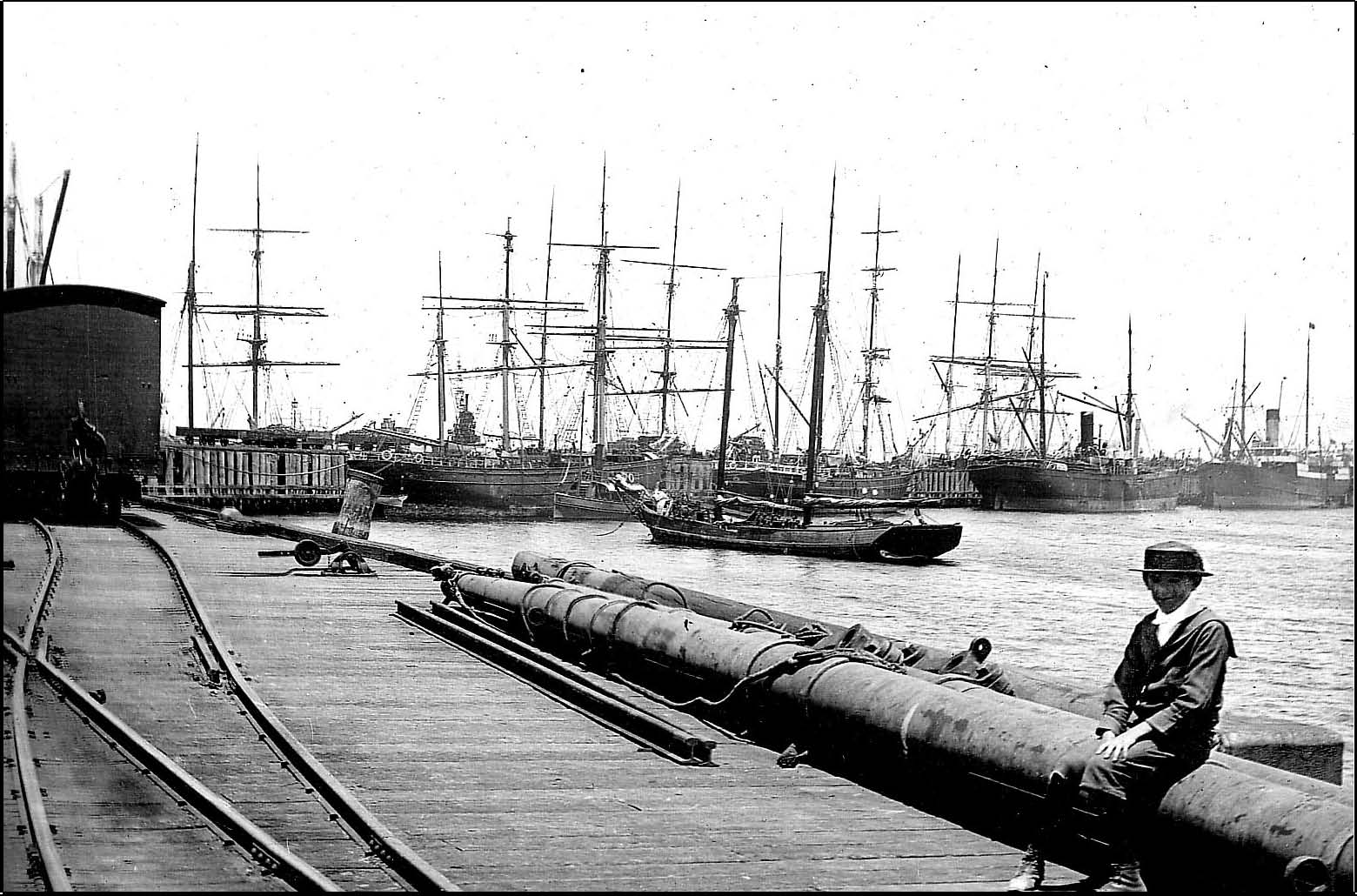

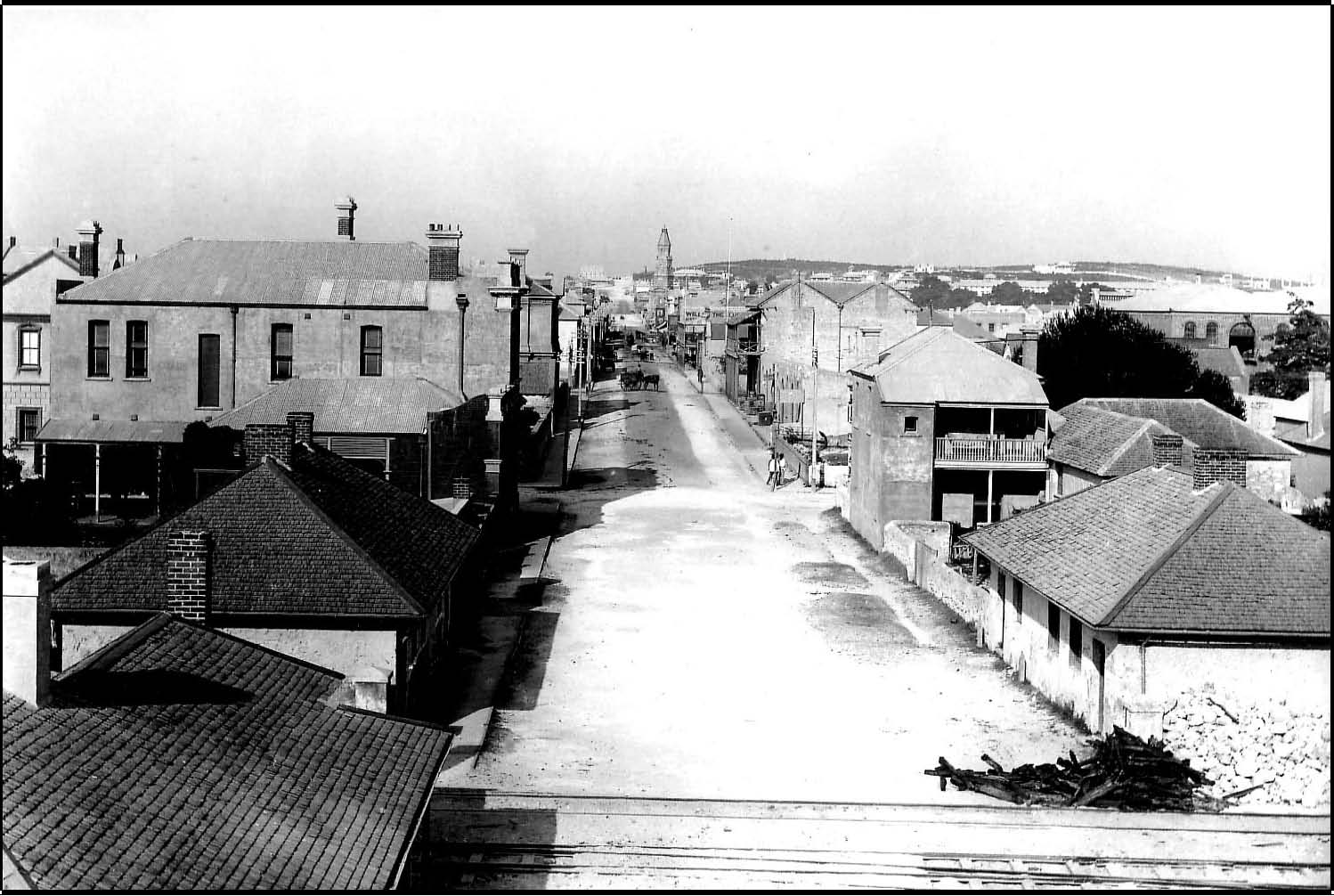

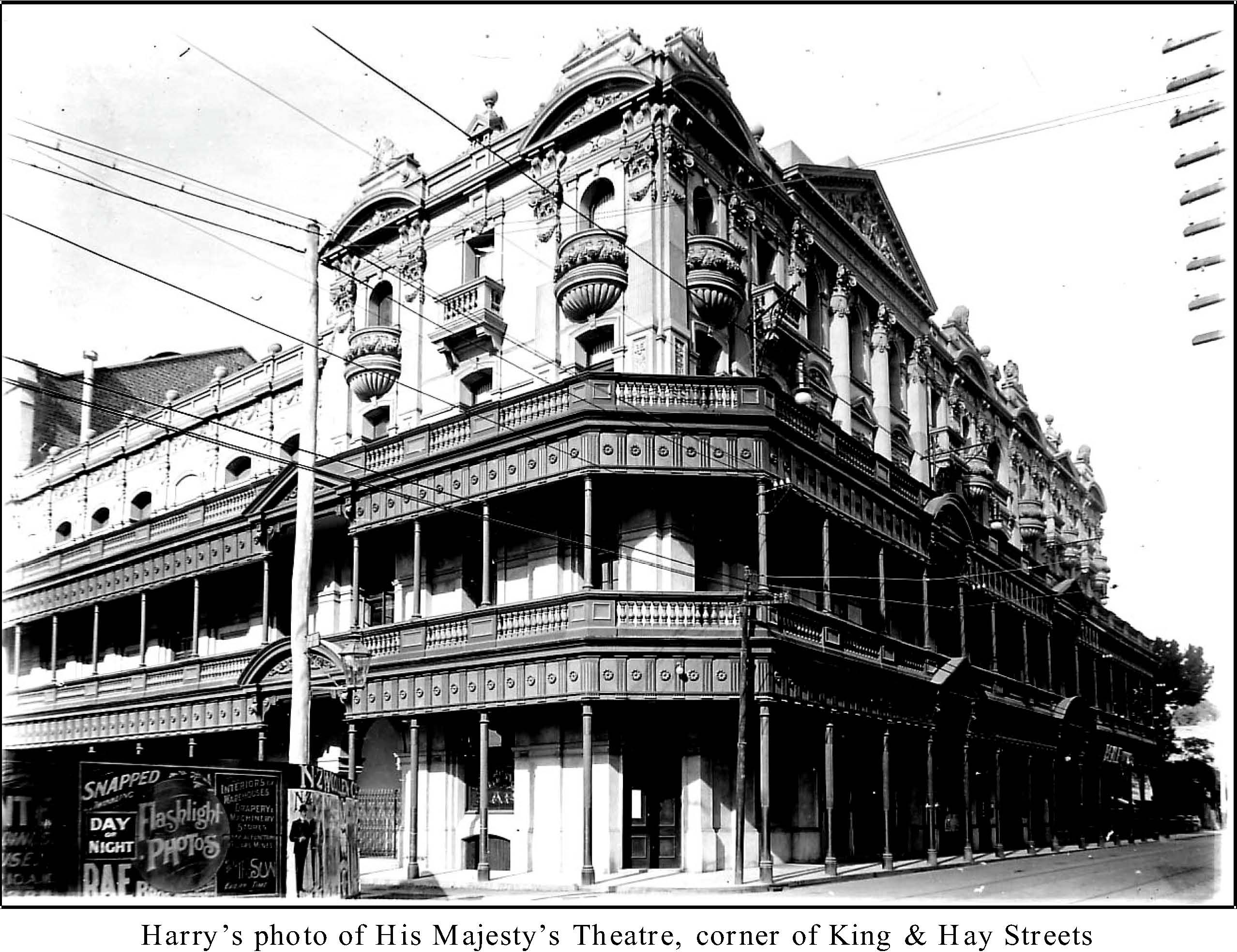

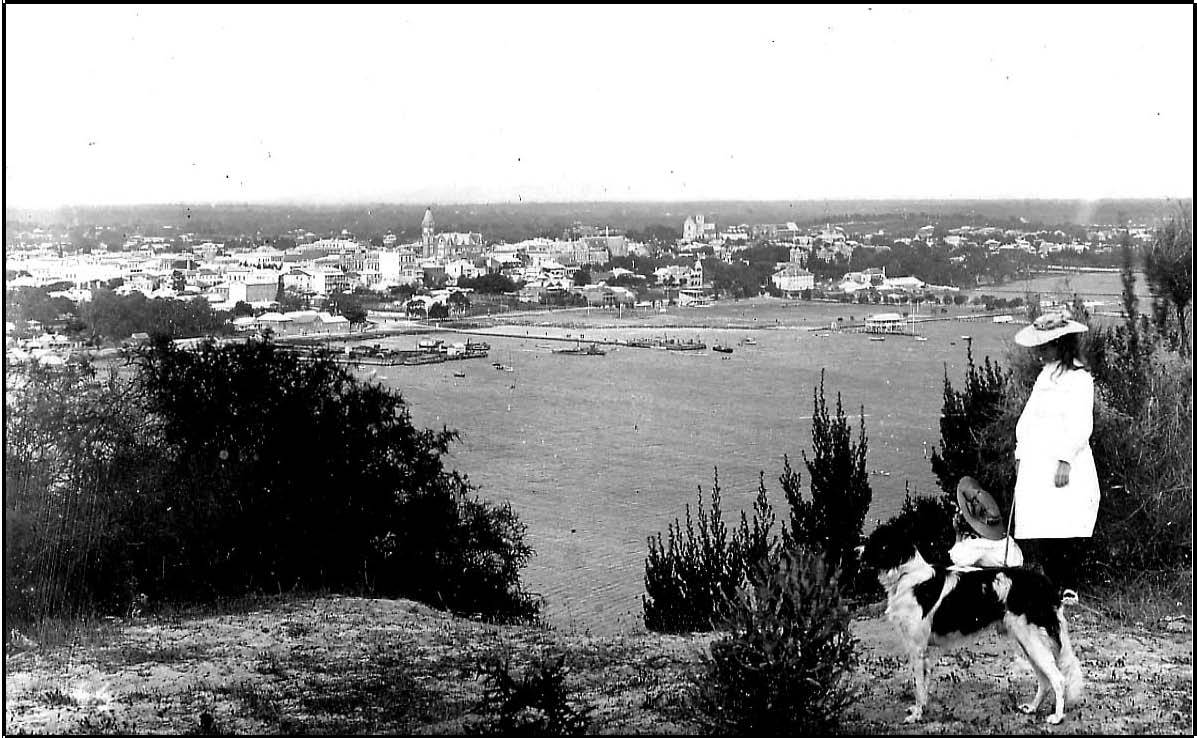

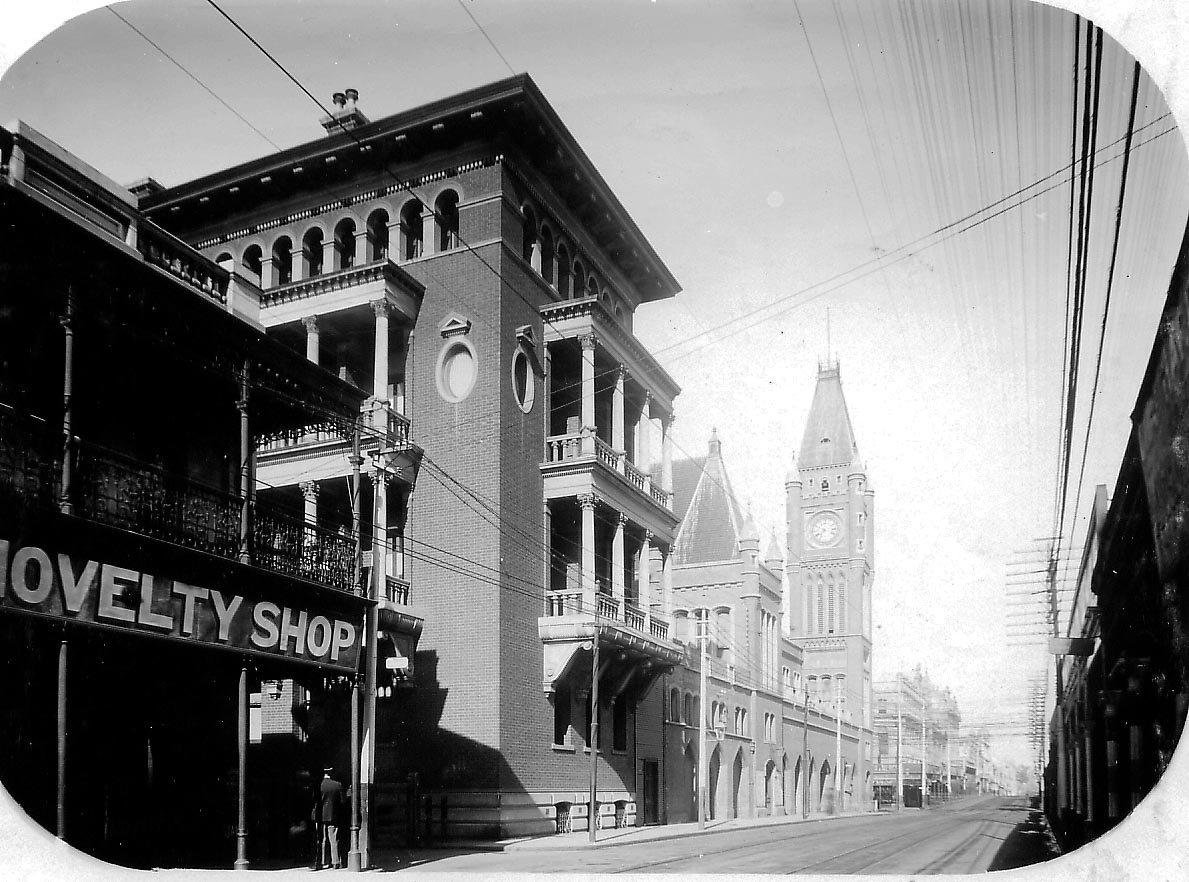

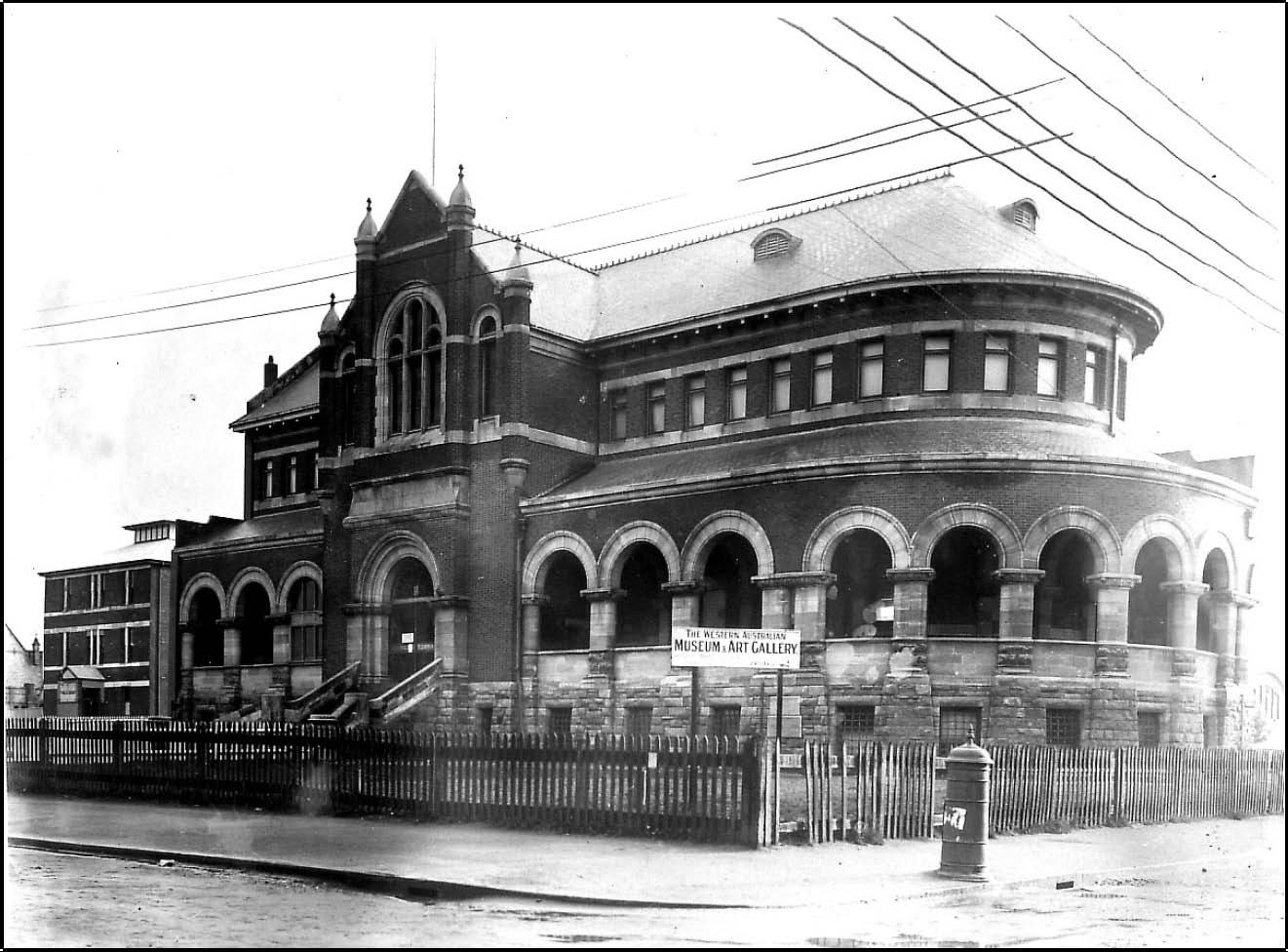

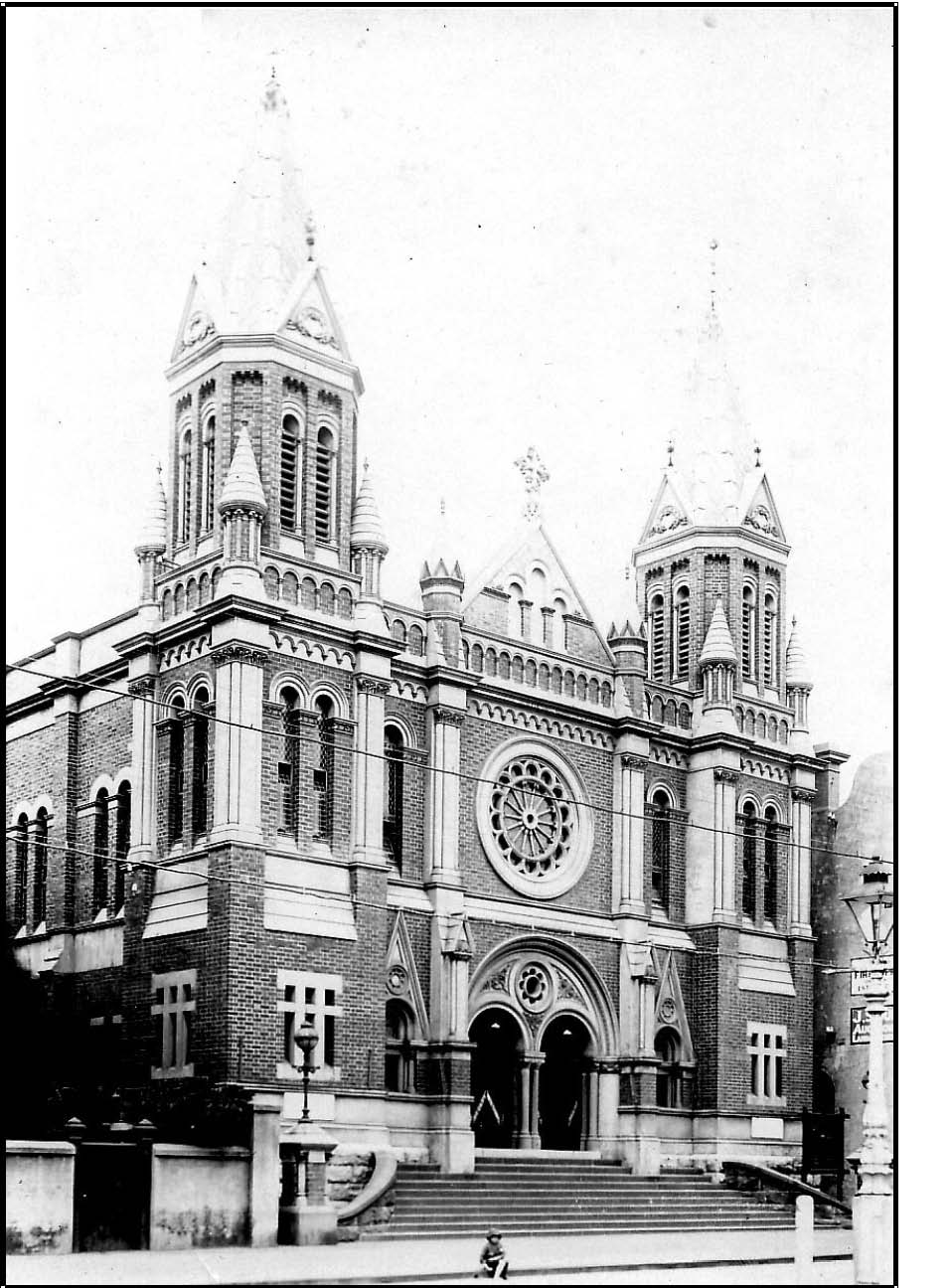

Photos of early Fremantle ......................................... 125

Harry’s transfer to Perth .......................................... 130

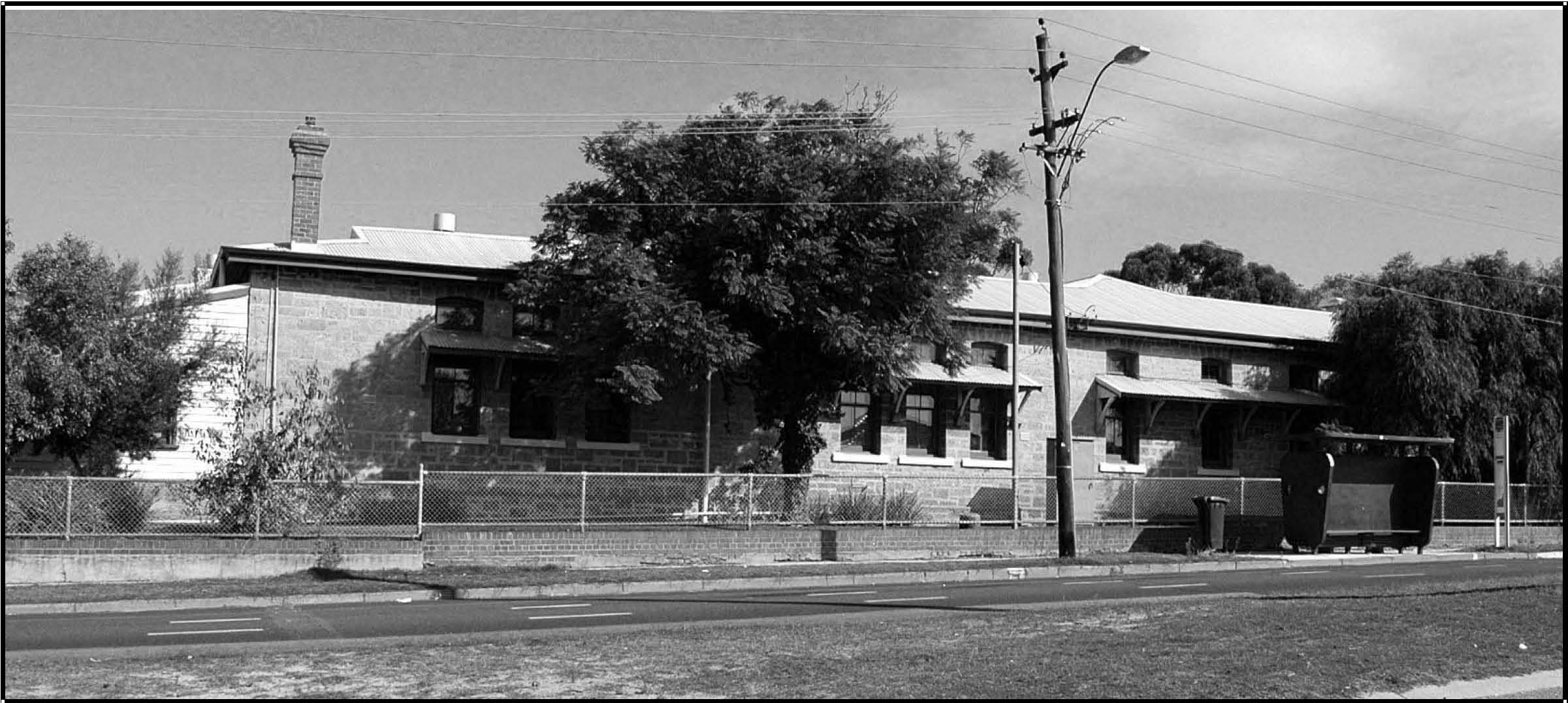

The Barracks ................................................... 131

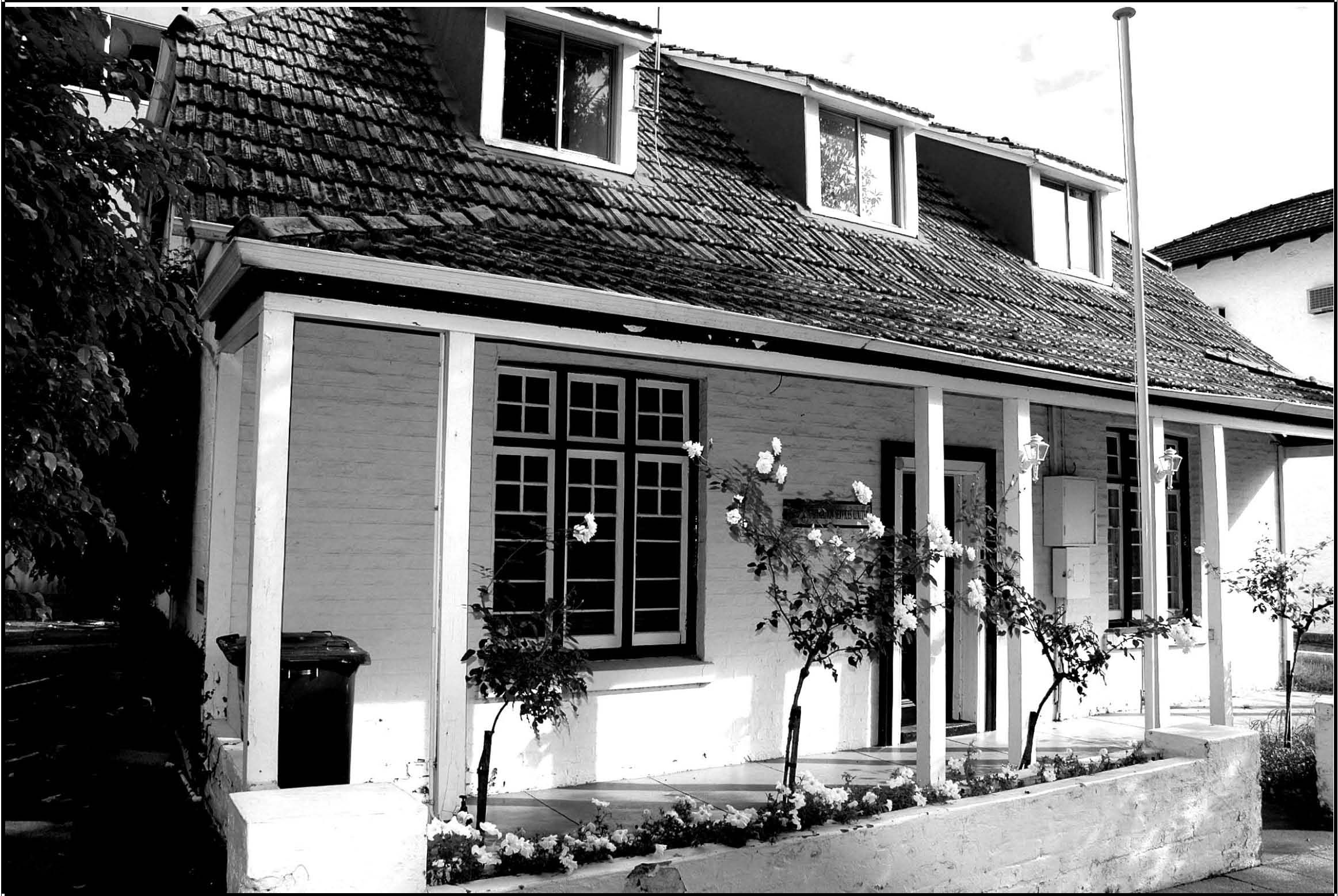

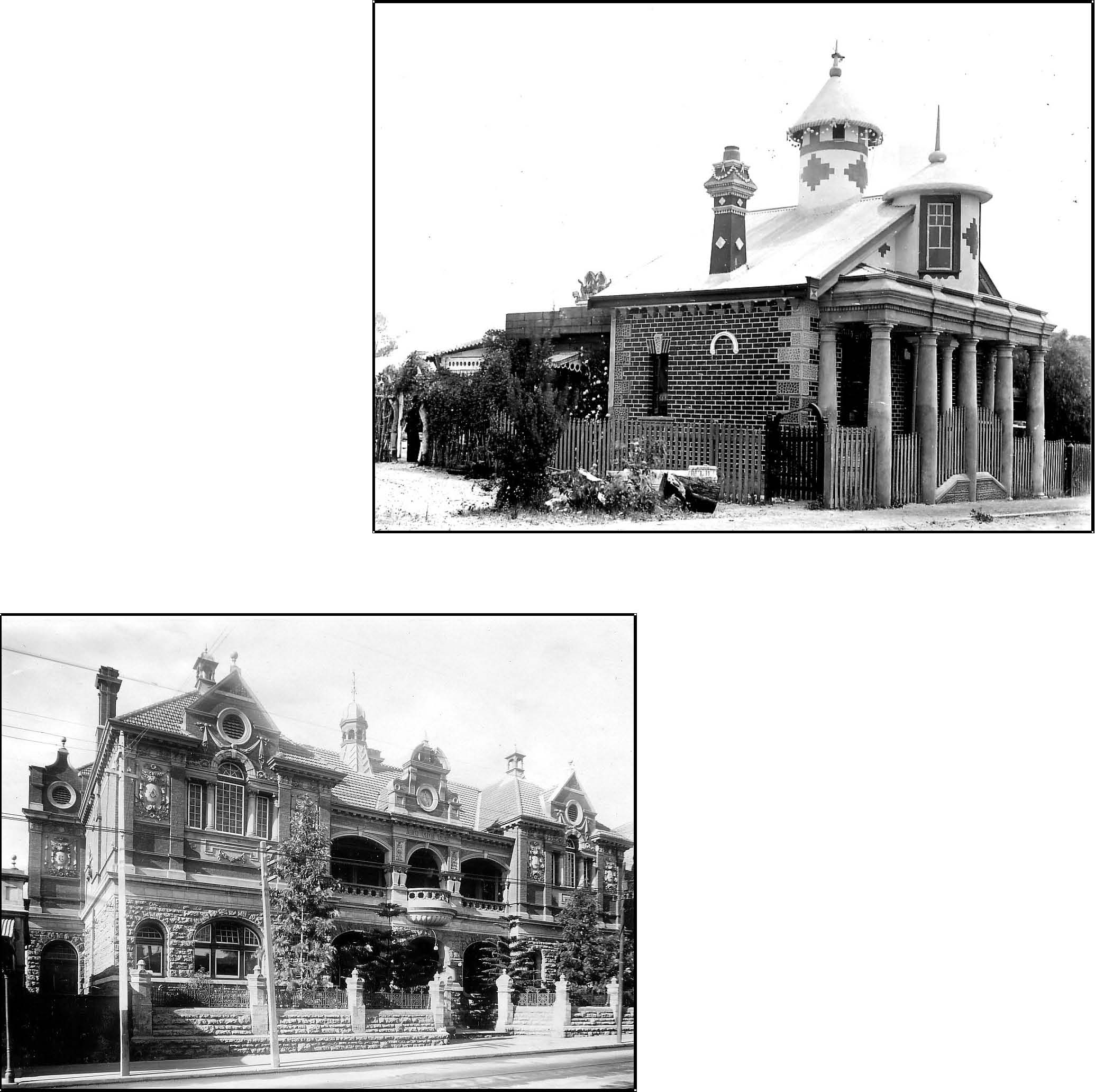

Their house in Colin Street, West Perth .............................. 132

Family photos, 1905 ............................................. 134

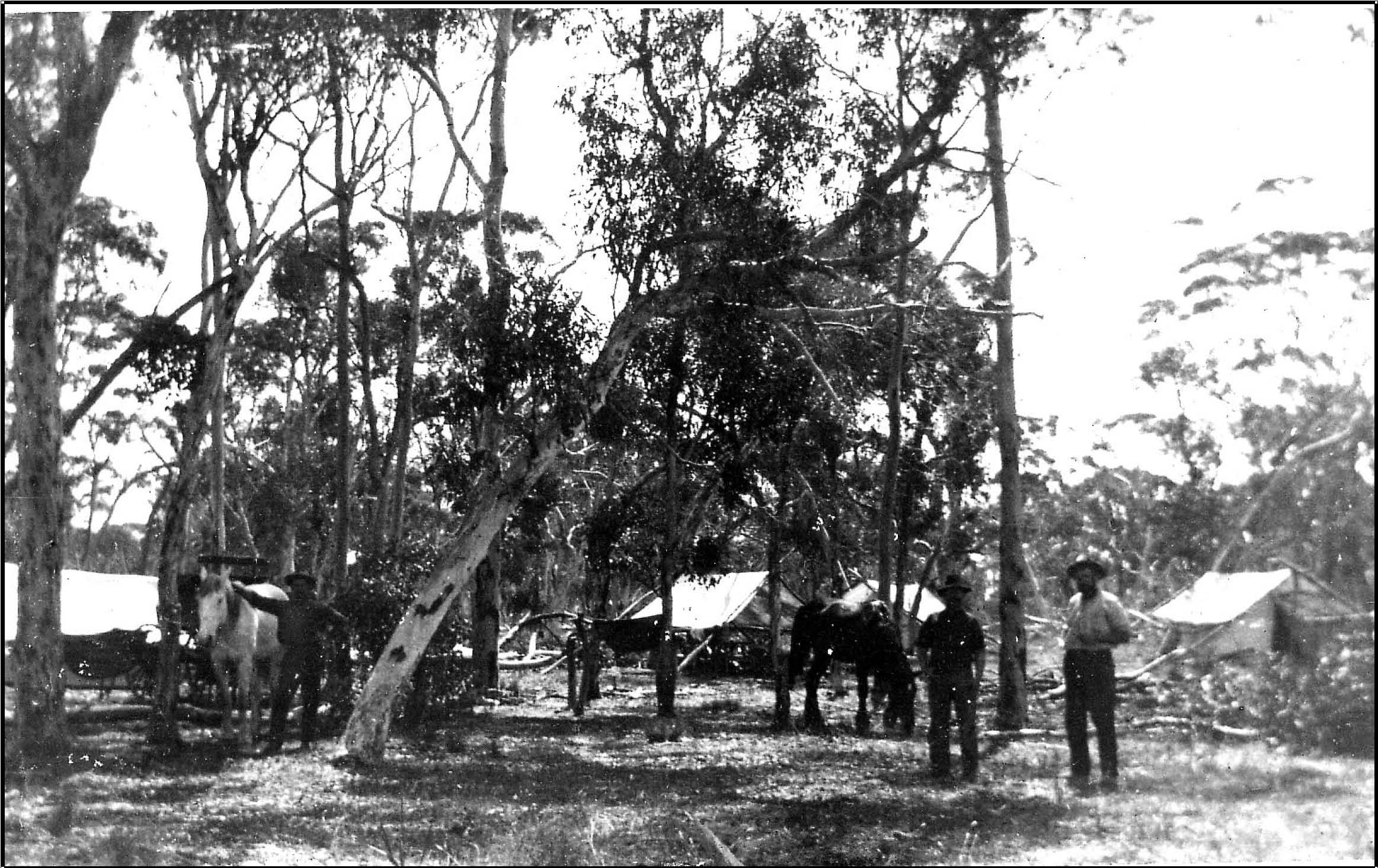

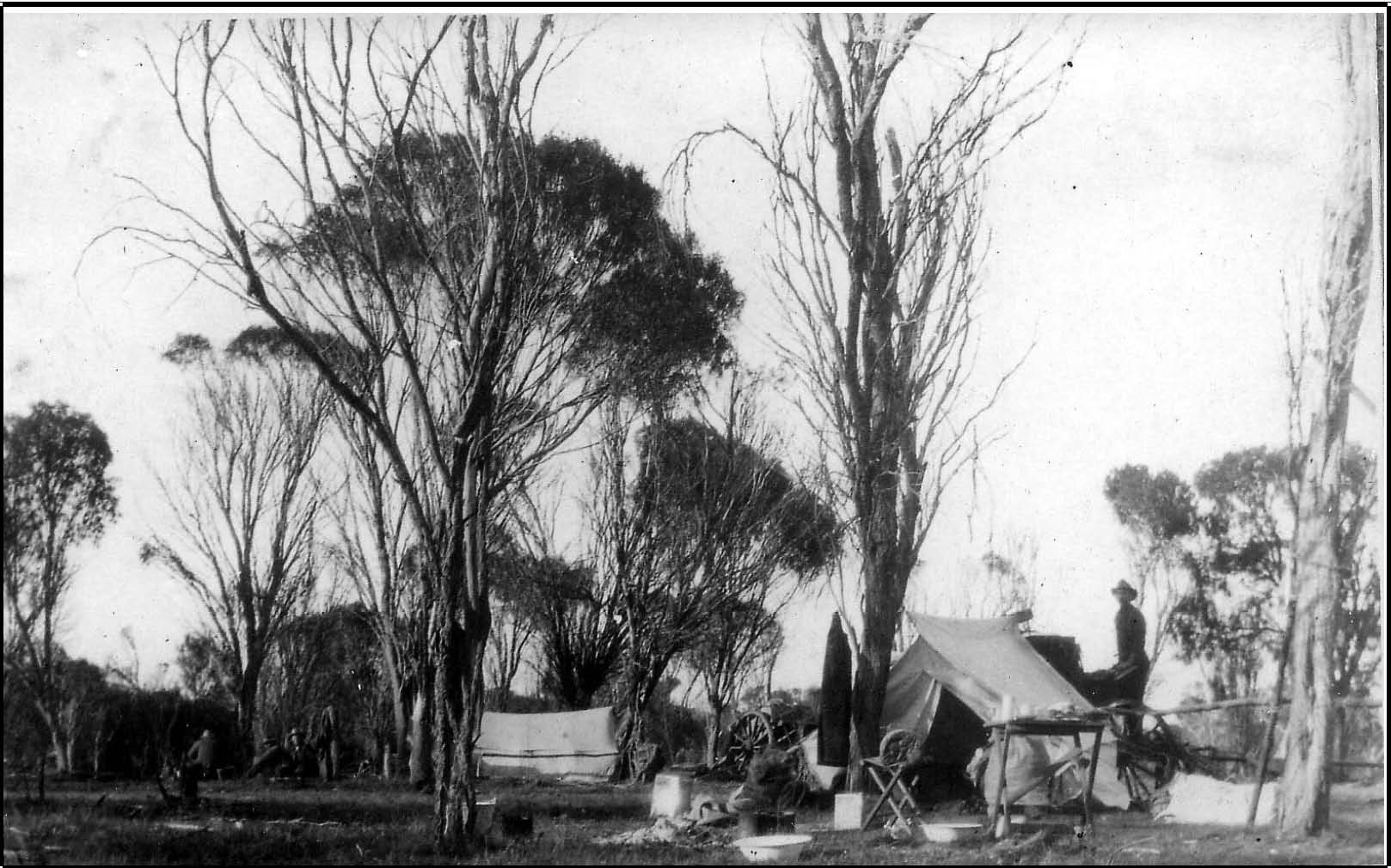

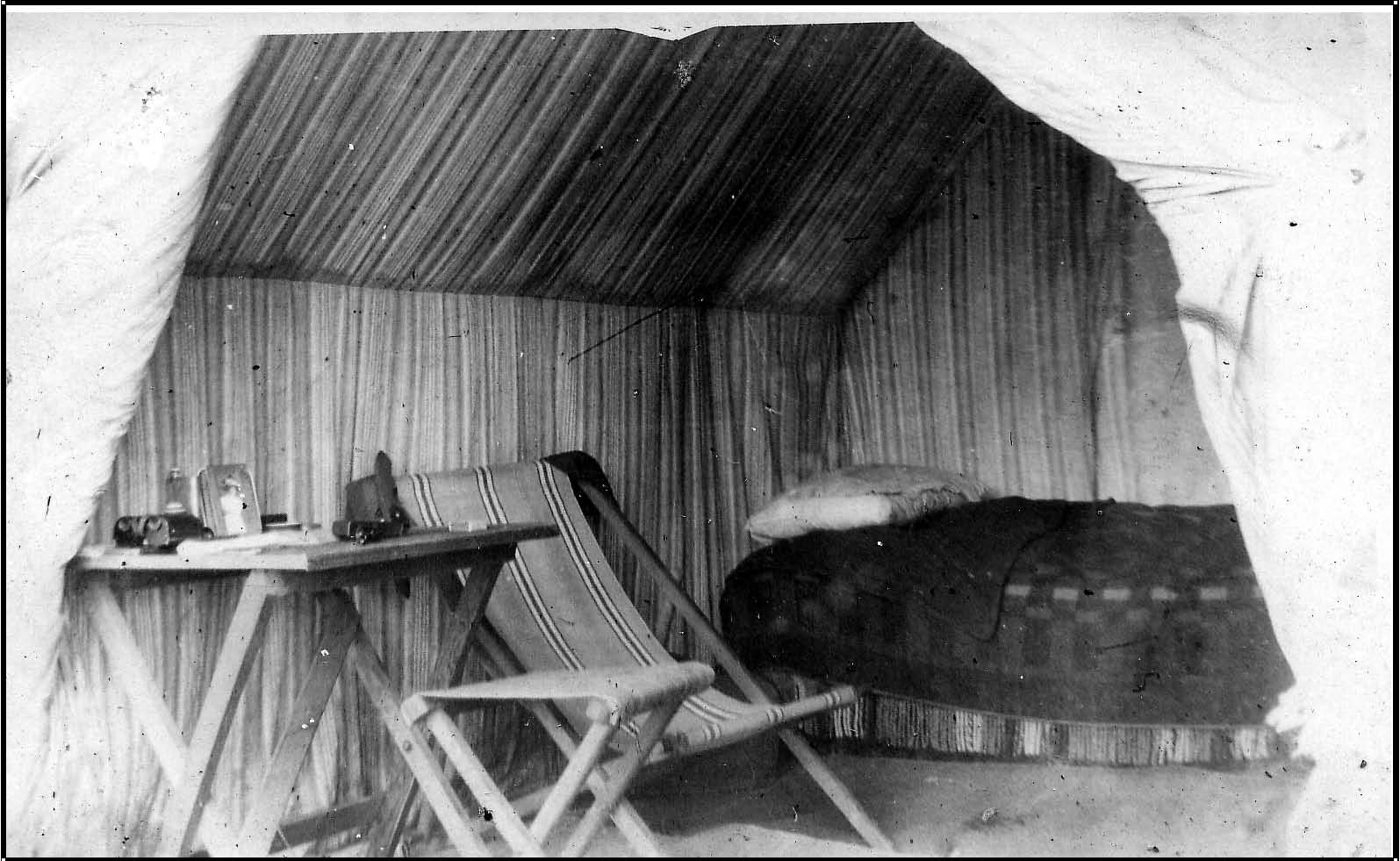

Harry’s work in the bush .......................................... 136

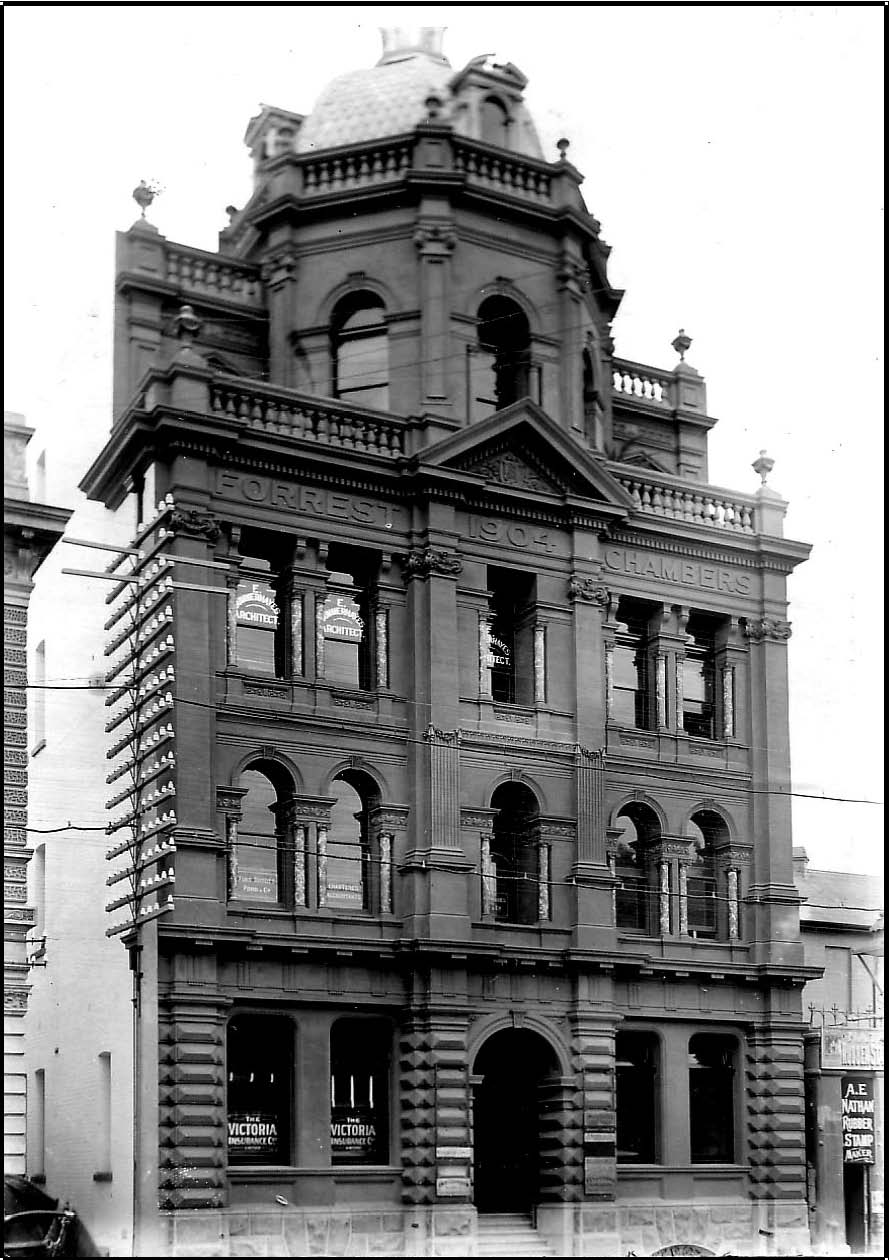

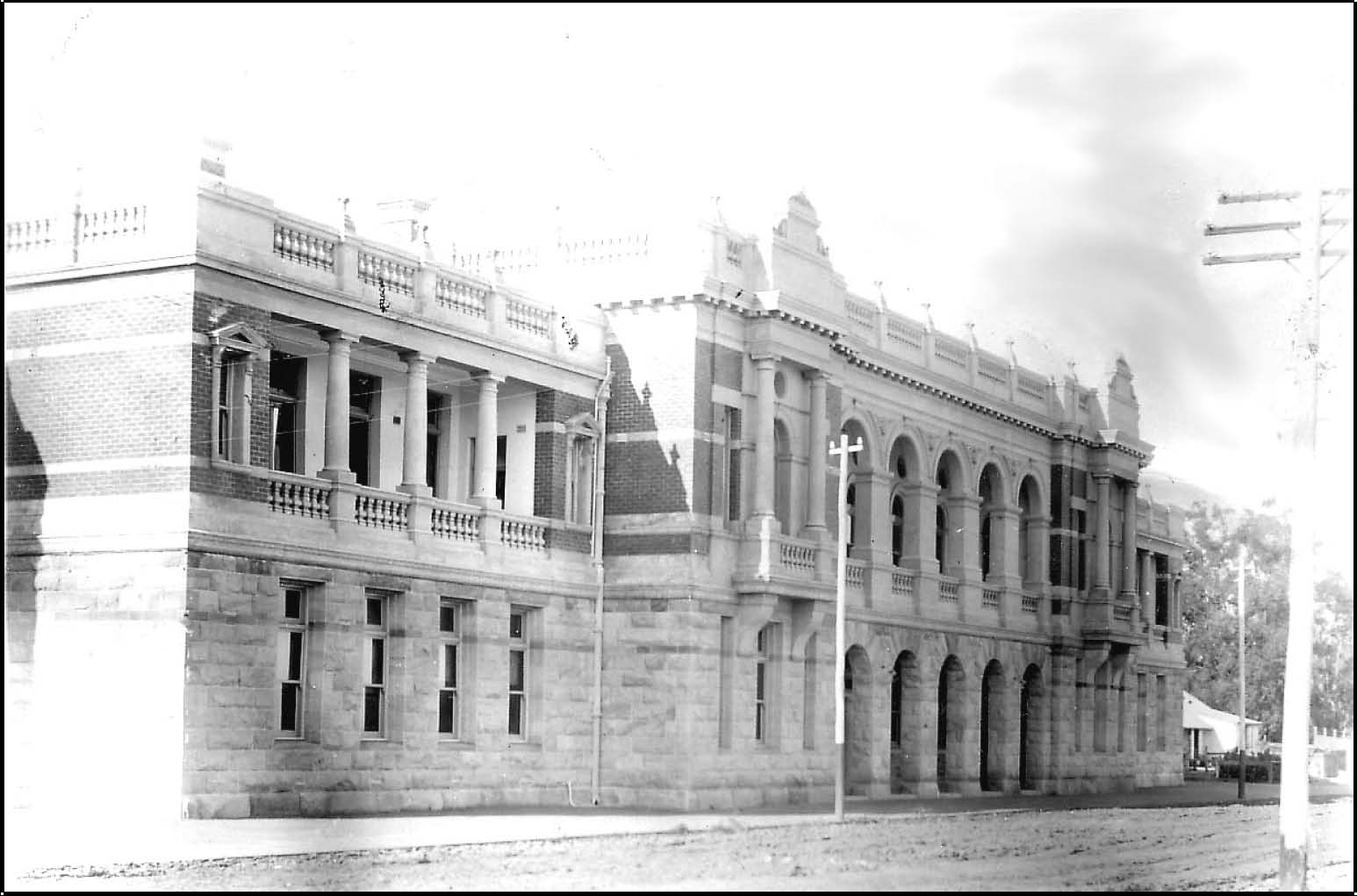

Harry’s photographic hobby: City buildings ........................... 138

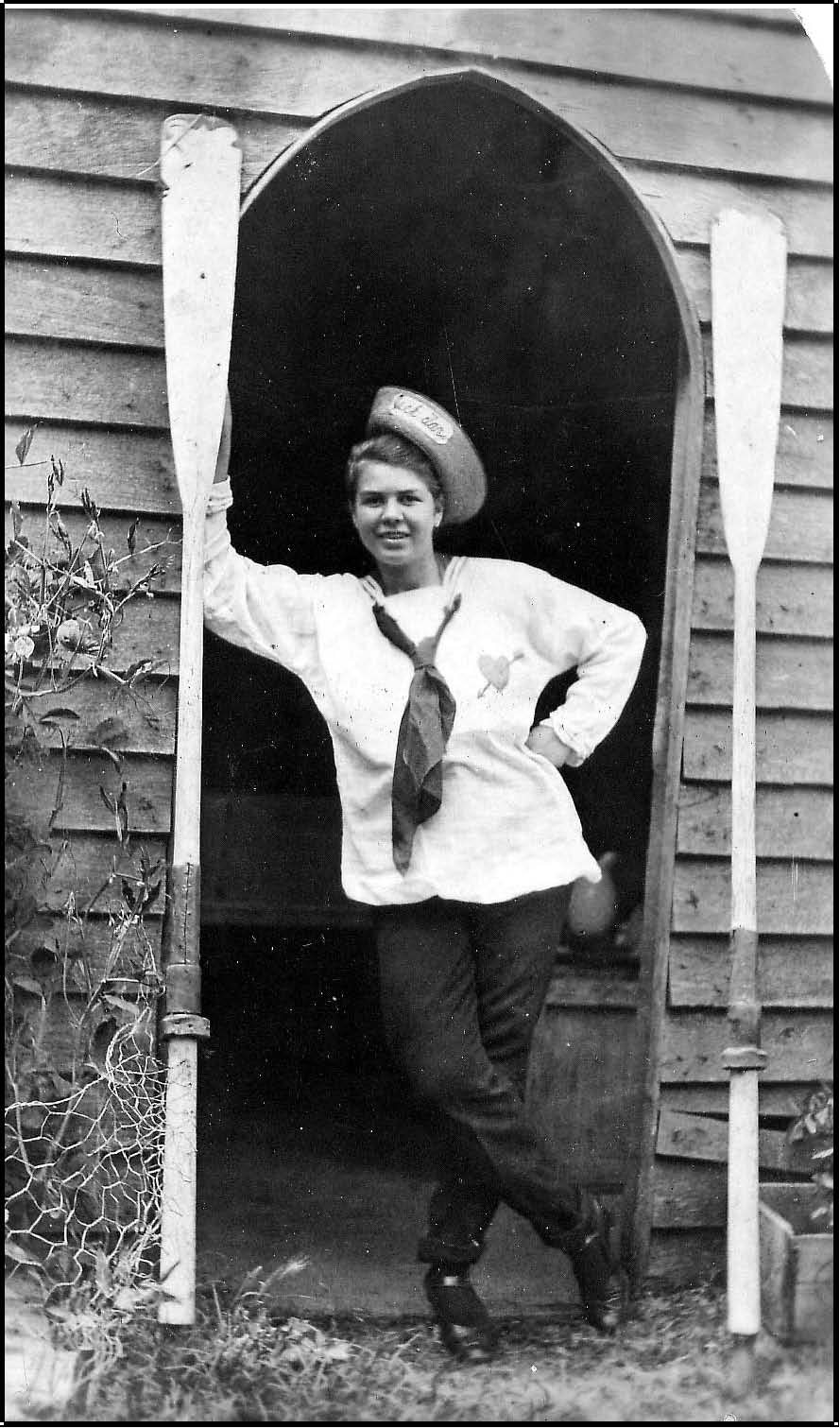

The years in Perth before transfer to Bunbury.......................... 145

Silver Wedding .............................................. 145

Harry’s problem with drink..................................... 146

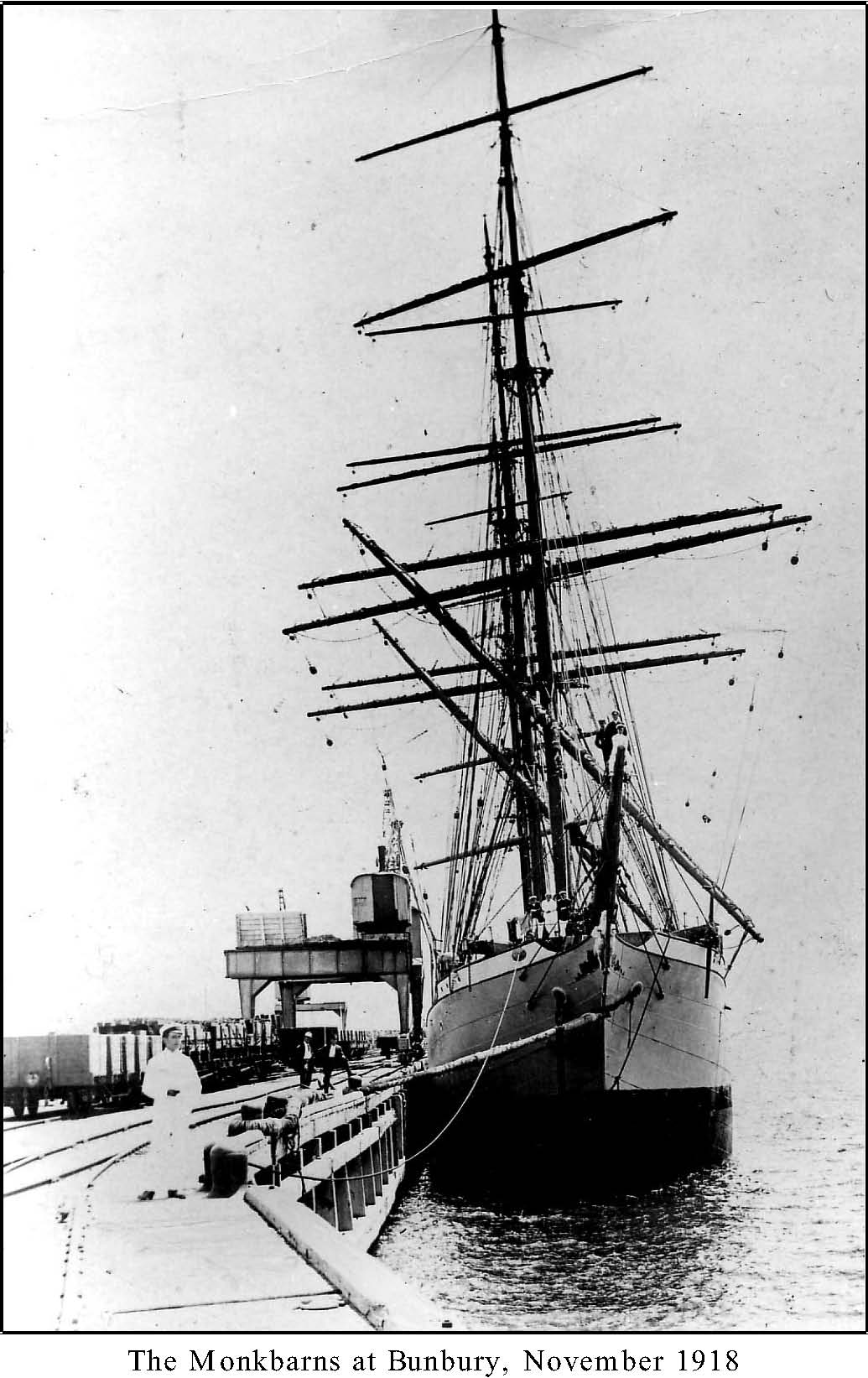

Harry becomes resident engineer at Bunbury .......................... 147

Blasting stone at Roelands ..................................... 148

Harry’s work ................................................ 149

Easter 1916 ................................................. 151

Harry’s motorcycle ........................................... 153

The First World War ............................................. 155

The End of World War I .......................................... 156

Their last days in Bunbury......................................... 161

Legacies received by Kate ......................................... 162

Short Holiday in Perth .......................................... 163

Buying a house in North Perth ...................................... 164

Geraldton Harbour Works ......................................... 166

Kate’s Death and Will ............................................ 167

Kate, Harry and Religion.......................................... 168

Harry Rumble’s eccentricities and problems........................... 170

Harry’s 80th birthday............................................. 176

Harry and Kate’s family Horace ........................................................ 177

Eric .......................................................... 179

Leslie ......................................................... 179

Maude ........................................................ 179

Euean Humfrey ................................................. 179

Phyllis ........................................................ 179

Dorothy Rumble [15016] ............................................. 180

The background of Victor George Fall [15016] ........................... 187

Rev. Edward Fall - my great-great-grandfather [12004].................. 187

Our search for Edward Fall ..................................... 191

Edward’s Bible flyleaf family record ............................. 192

Descendants of Edward Fall ....................................... 197

Edward Fall’s family ............................................. 197

Edward’s daughters: Emma, Hannah, Mary, Susanna & Rebekah ....... 198

Thomas Fall[13024] .......................................... 198

James Fall - my great grandfather [13010] ......................... 198

Long Buckby ................................................... 200

1884 Ordnance Survey map .................................... 202

The Family of James & Louisa Fall .............................. 204

George Edward Fall - my grandfather [14018] ......................... 204

Long Buckby’s background .................................... 205

George Fall’s clothing business ................................. 206

We visit the Firs ............................................. 207

Long Buckby photos .......................................209-212

George Fall’s marriage & Family ................................ 213

The descendants of John McNamara (Chart) ................. 214

The McNamara Family ................................. 215

The Children of George & Emily Fall ...................... 215

Victor George Fall .................................................. 217

Victor goes to sea ............................................... 219

Victor’s indenture papers ...................................... 220

Life at sea .................................................. 221

Victor and Dorothy ................................................. 230

Victor migrates and joins Millars’ Timber & Trading Company ........... 235

Fifty years of Forestry in Western Australia ........................... 236

Photographs of the early timber industry ............................. 237

and Dolly become engaged..................................... 239

Their wedding photograph ..................................... 240

Married Life at Mornington Mills ................................... 241

Transfer to Yarloop .............................................. 244

The town of Yarloop .......................................... 245

The Workshops ....................................... 246

Life in Yarloop The birth of Dorothy Joan ............................... 250

The birth of John Victor................................. 251

The Great Depression of the Thirties ................................ 254

v vii

is promoted to Chief Clerk ..................................... 255

My memories of living in the Yarloop House .......................... 257

Victor and Douglas Social Credit ................................... 259

Yarloop Annual Sports Day........................................ 260

Vic’s interest in Aircraft .......................................... 264

The Yarloop swimming pool ....................................... 265

The Baby Ford car ............................................... 266

The move to the city ............................................. 267

The Second World War ........................................... 268

joins the RAF: Singapore & Malaya .......................... 269

Japan enters the war: Victor becomes a prisoner of war ............... 272

Life as a prisoner of war................................. 273

Dorothy’s life during this period .......................... 275

The end of the war: Vic returns home ............................. 275

Pictures from POW Camp, Java ................................. 277

Settling back into civilian life ...................................... 278

Joan becomes engaged & travels to the US......................... 270

Vic’s recovery ............................................... 282

Retirement - a home in Warnbro, then in Shoalwater Bay ................ 284

Extended holidays ............................................ 285

The Rockingham Historical Society .............................. 286

takes up writing and published two books ...................... 286

The Death of Victor in 1974 .................................... 288

Dorothy’s life after the death of Victor ............................... 288

Joan and Joe visit Western Australia.............................. 290

Dorothy moves to Wearne hostel ................................ 291

second visit from Joan ....................................... 292

The death of Dorothy ......................................... 293

Dorothy’s descendants ........................................294 - 295

Appendix I - Old Bailey transcript re burglary of Valentine Knight ............ 296

John Fall

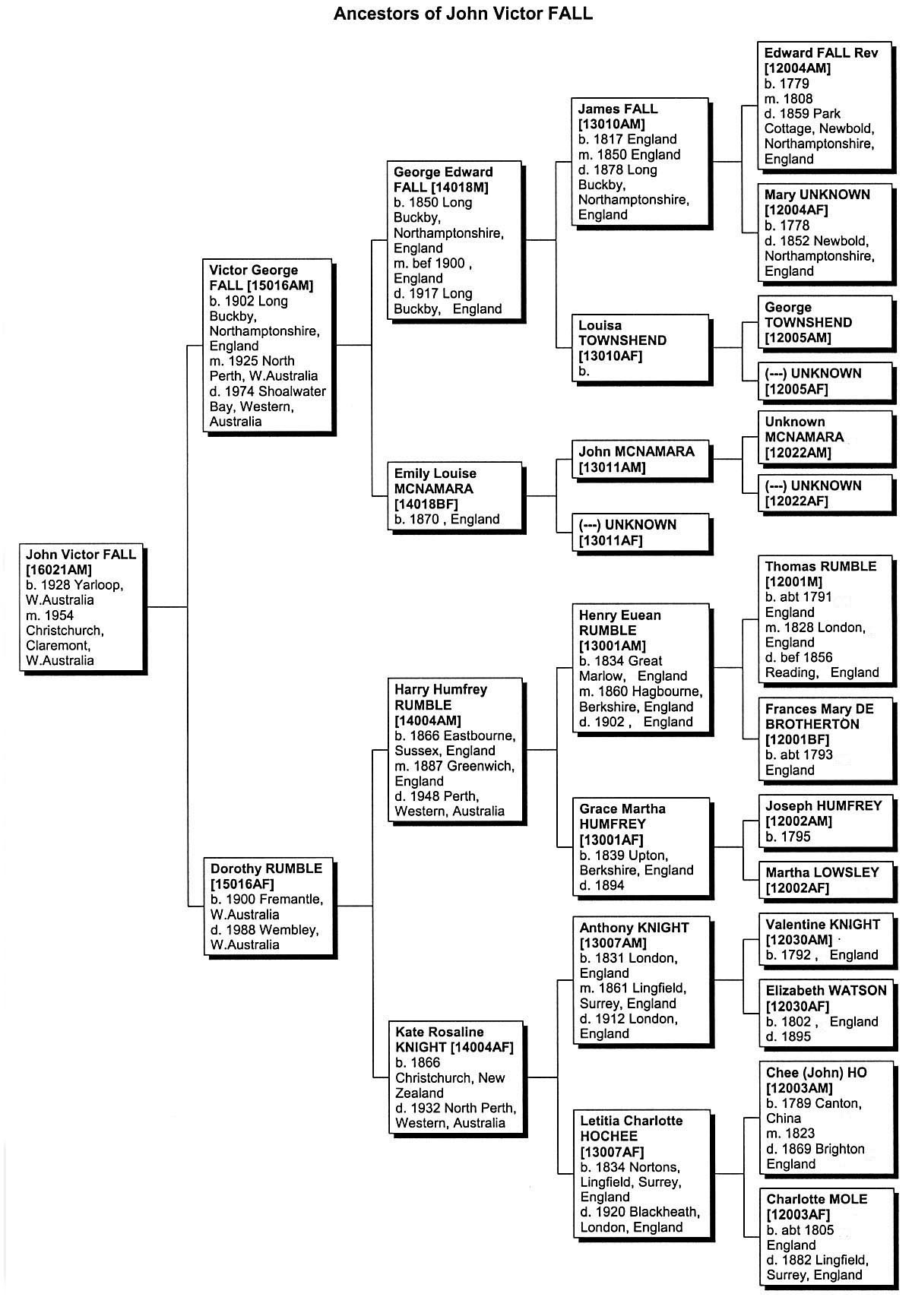

My Ancestral Tree - Back to Great-Great-Grandparents

here

are many reasons why I decided to search for my ancestors.

here

are many reasons why I decided to search for my ancestors.

Between 1958 and 1960 I spent some time in Britain, and sought out the gravestones of a few of my forebears; I have portraits and

photos of grandfathers, great-grandfathers and even of a great-great grandfather. My mother spoke of my Chinese ancestry, while my father told me of a great-great grandfather, the Reverend Edward Fall, a Baptist minister in Rugby, who was known as the “Silver tongued.”

Of course, with a minimum of information it is possible to draw a chart of one’s ancestors, as I have done on the preceding page - but this tells us nothing about the people apart from where they fit in the family.

On the left in the chart, we start with myself and then my parents, Victor Fall and Dorothy Rumble, while on the right we have my great-great grandparents. In a few cases - for the Knights and the Humfreys - I can trace back to earlier generations. Excluding myself, this chart could include thirty ancestors but, unfortunately, we do not have details for them all.

But as orderly and as attractive as this chart may be, it is not how we actually find our ancestors. It is too logical, and too neatly laid out. In reality we find them by following leads from various sources - from family records, letters, old photos, census records and even from family folklore passed on by word of mouth.

We find items of “truth”, record them, and then our search changes course; or we find new leads which sometimes lead to contradictions and the need to revise our “truth” .

The search I am about to present, is not orderly but will twist and turn. Although I started half-heartedly in the 1950s, and then tackled it earnestly from 1989 onward, there is no better way to illustrate the random path of progress than to start with Andy Williams, a second cousin of mine, removed by one generation, and whom I did not discover until 2002.

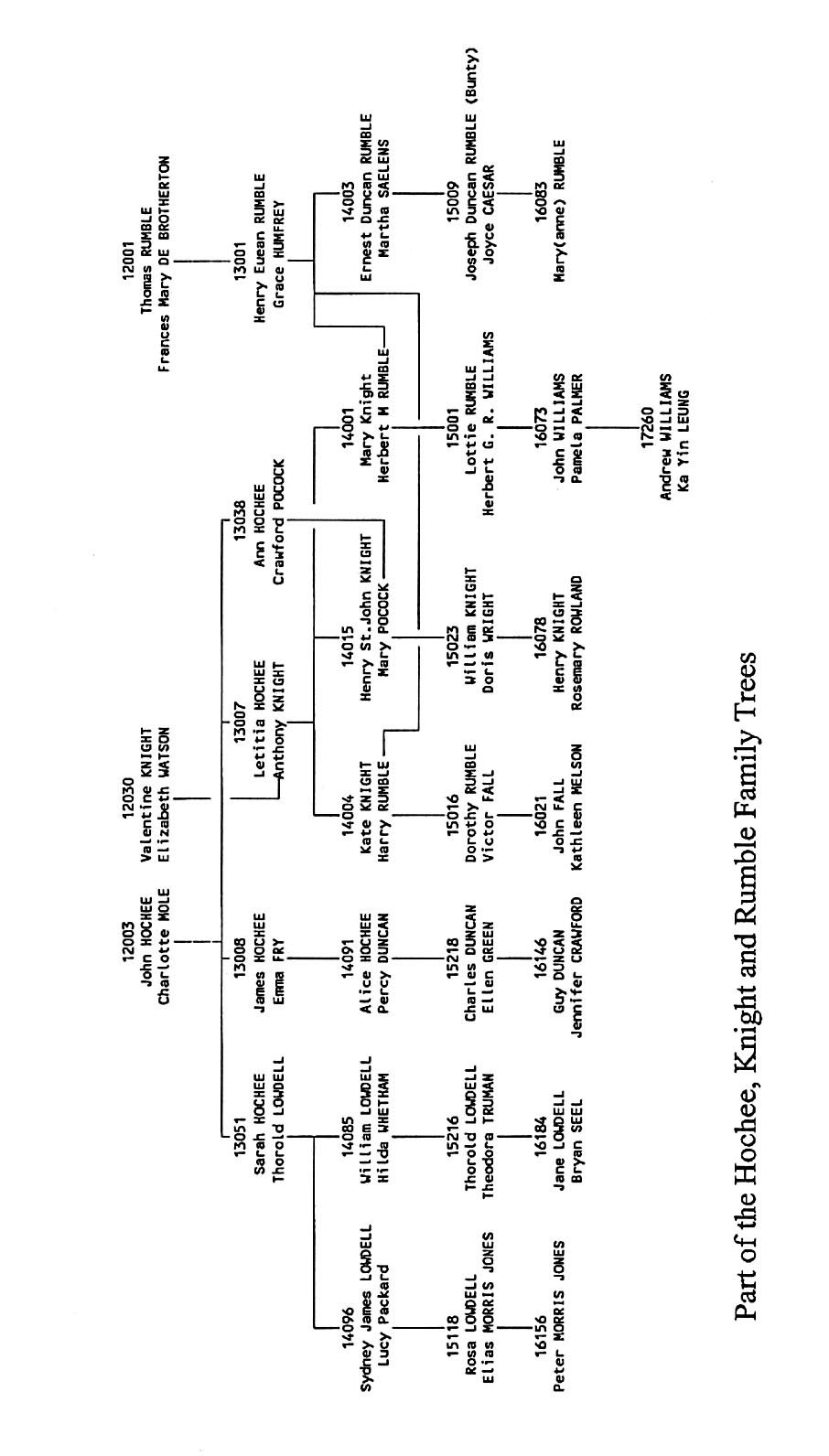

Found in Andy Williams’ Attic: Left to right - Elizabeth Watson 12030AF (b1802) who married Valentine Knight 12030AM, her son Anthony Knight 13007AM (b1831), his daughter Mary Knight 14001AF (b~1872) who married Herbert Rumble 14001AM, and their daughter Lottie Rumble 15001AF (b1893). My grandmother Kate Knight was Mary’s sister, while Kate’s husband was Harry Humfrey Rumble, brother of Herbert Rumble

FOUR GENERATIONS

![]() ndy Williams was born in 1957 and is almost the same age

as my son Peter. Until 2002 I had never heard of him. Andy married a

Chinese girl Ka-Yin Leung from Hong Kong and in 2000 they had a

daughter, Maya. Two years later he decided to track down the family

legend that he had a Chinese ancestor of his own, but everyone in the

family seemed very vague about it. Early in 2002 he recalled:

ndy Williams was born in 1957 and is almost the same age

as my son Peter. Until 2002 I had never heard of him. Andy married a

Chinese girl Ka-Yin Leung from Hong Kong and in 2000 they had a

daughter, Maya. Two years later he decided to track down the family

legend that he had a Chinese ancestor of his own, but everyone in the

family seemed very vague about it. Early in 2002 he recalled:

My grandmother, Lottie, always claimed that she had a Chinese ancestor. She said that he was a Chinese merchant with a pig-tail, but didn’t know his name or how far back he was in history. Lottie was a scatterbrained lady: great fun, a very good artist, woodcarver and cook, but hard facts were not her strong suit.

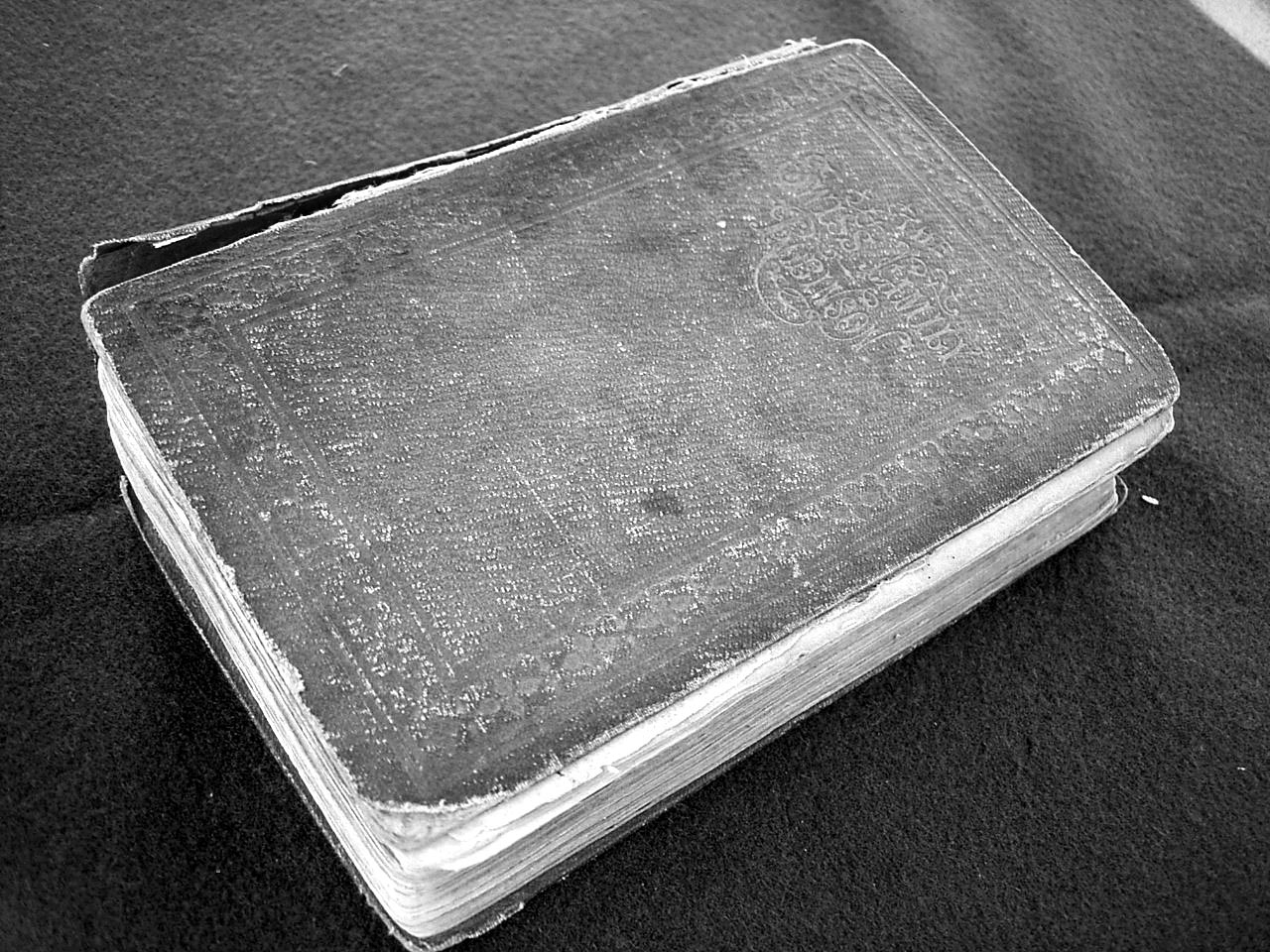

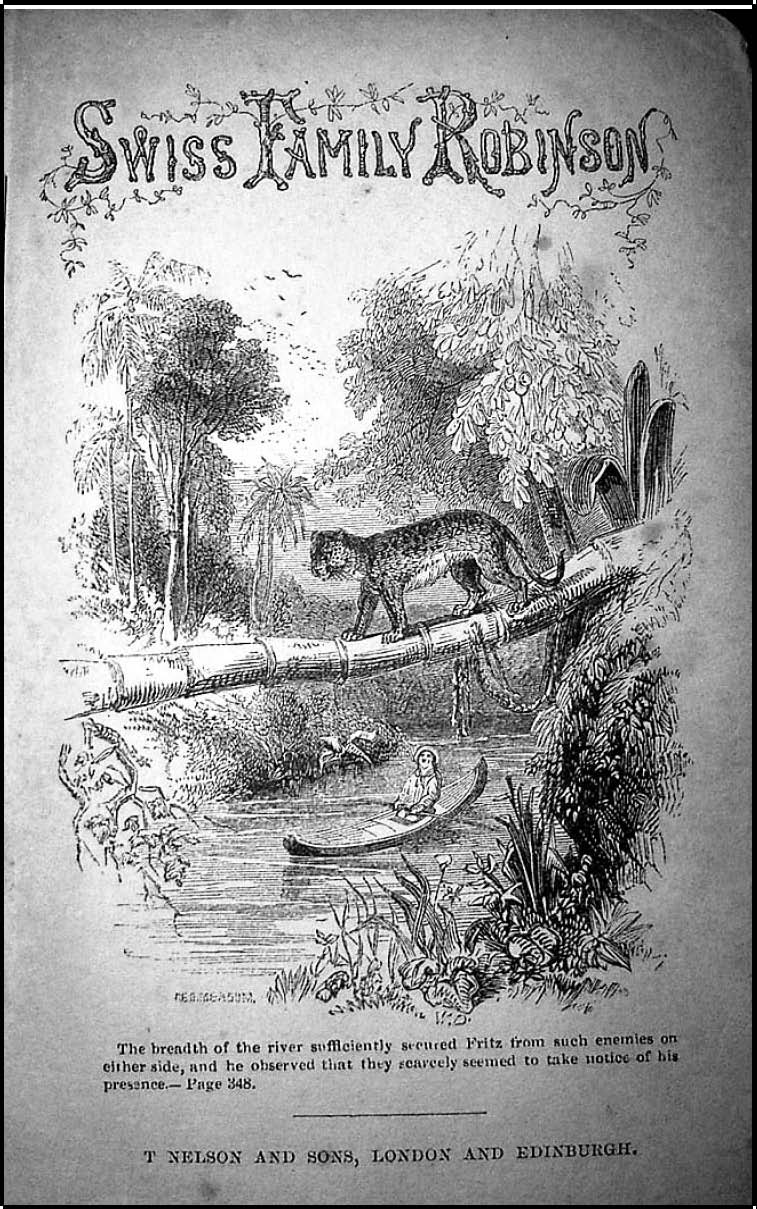

Lottie’s husband, Herbert Graham Rickard* Williams, on the other hand, was very keen on tracing his family. With the help of the family bible and quite a few old documents, he traced the Williams’ line back to 1640, and a baronetcy which he missed by a whisker. (* NOTE: ‘Rickard’ is the correct spelling, with a ‘k’)

My dad, John Williams, who died in May 2001, was strangely uninterested in his Rumble relatives and ancestors. He dismissed the Chinese ancestor as “just one of Mum’s stories”.

Andy decided to rummage around in the attic of their home at Stroud in Gloucestershire, UK. He knew that many of his grandfather’s old belongings were there, probably covered in dust. Unexpectedly he found a fine old metal bowl in a box of his grandfather’s belongings that had been stored there for 15 years since Herbert had died. Ka-Yin identified it as being of Chinese origin from the early Ming dynasty in the sixteenth century. Maybe there was some truth in a Chinese background to his family! He became obsessed with finding out.

He also found two other items of interest: One was an old photograph titled

- FOUR GENERATIONS - 1/7/94

as reproduced on the previous page. Beneath the picture itself (but not shown on our reproduction here) was the handwritten name of his grandmother: Lottie. He knew that Lottie had been born on 17 May 1893 - so the baby in

the photo tallied with the name. Andy presumed that she was sitting on the lap of her mother, Mary Rumble - so that accounted for two of the four generations. But who were the other two people? He did not know. Tracking down their identity lay in the future and would involve other family members of whom, at that time, he had never heard.

The next clue that Andy found was a newspaper cutting that dropped out of one of his grandfather’s books in the attic. It referred to a Horace Rumble in Perth, Western Australia. Andy recalled:

When my Mum Pamela pointed out that Horace was my grandmother’s cousin,

not brother, I assumed that that his line couldn’t help much in my quest for the

Knights, but I decided to follow it up, just in case.

ANDY WILLIAMS AND HIS FAMILY SEARCH

ANDY WILLIAMS FINDS HIS WIDER FAMILY 7

The old newspaper cutting that Andy had found referred to Horace Rumble as the oldest member of the Royal Perth Yacht Club in Western Australia. Andy, was not only the same age as my son, but worked in the same industry - in the area of electronics and integrated circuits, so he was very familiar with computers. It did not take him long to find the Internet web address for the yacht club1. He wrote an email to them enquiring about Horace Rumble, not knowing that my uncle Horace had died long ago in December 1989. Fortunately Horace’s son, Peter, was still a member of the club, and the club contacted him.

In 1994 I had written a Who’s Who of the Rumble family2, but Peter could not find Andrew Williams within his copy, so he phoned me and gave me Andy’s email address. I already knew that Lottie Rumble had married Herbert Williams and I had a record of one son, John. I emailed Andy and asked if he was the son of John Williams. He replied that he was - being the second of four children. Soon he knew much about John Hochee and his Chinese Ancestry, and I put him in touch with my second cousin Henry Knight and third cousin Guy Duncan both of whom had completed research into the family. I had already encountered both of these people in my earlier research.

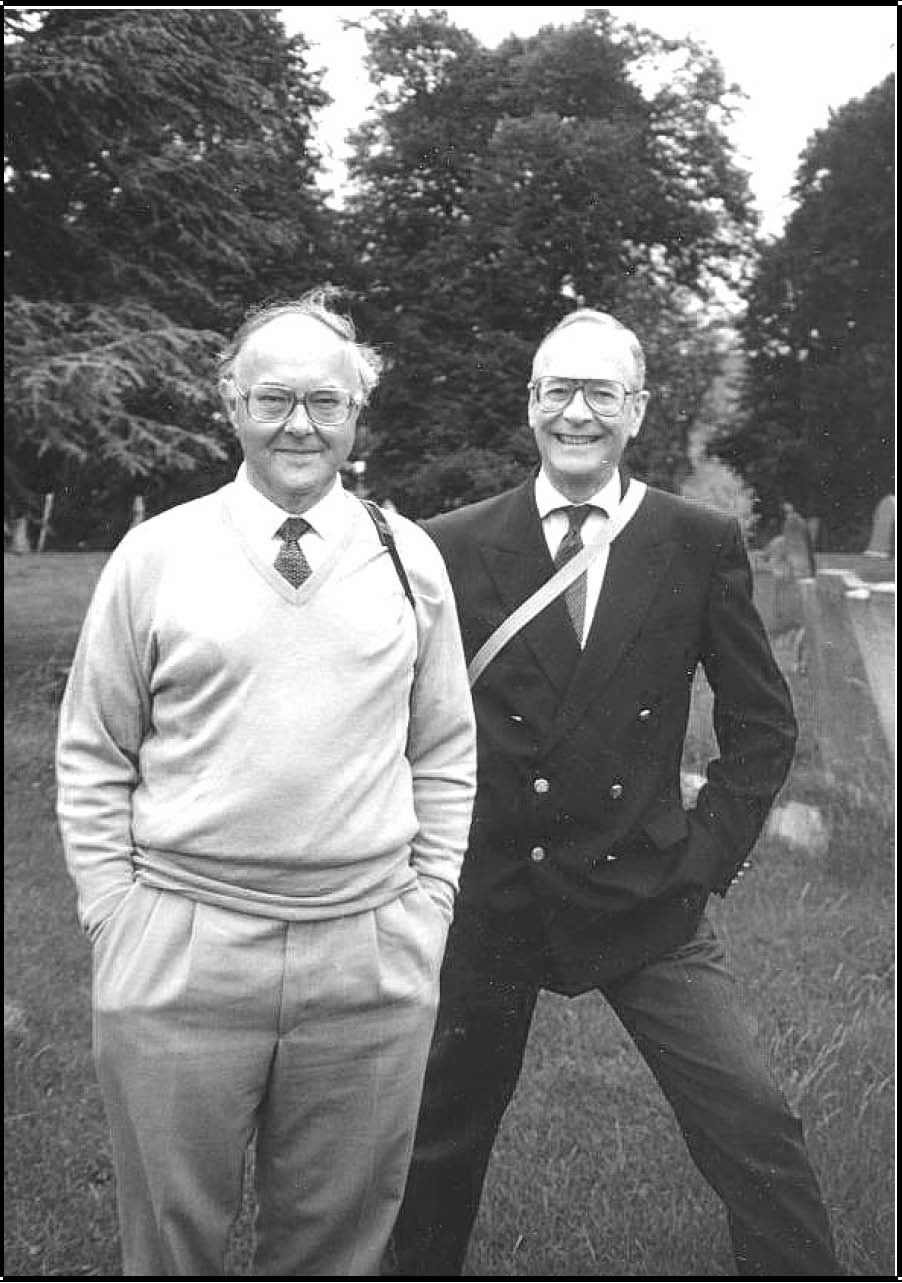

Photo

of John Fall and Guy Duncan, 2008.

We were still in doubt about the identity of the remaining two people in the “Four Generations” photograph. Andy, Henry Knight and his wife Rosemary, my wife Kay and I debated the issue at length. We finally established that the man was Anthony Knight - the father of both Mary Knight and of my own grandmother, Kate Knight. There was a double connection in the family as the two girls, Mary and Kate, had married two brothers, Herbert Rumble and Harry Humfrey Rumble, my grandfather.

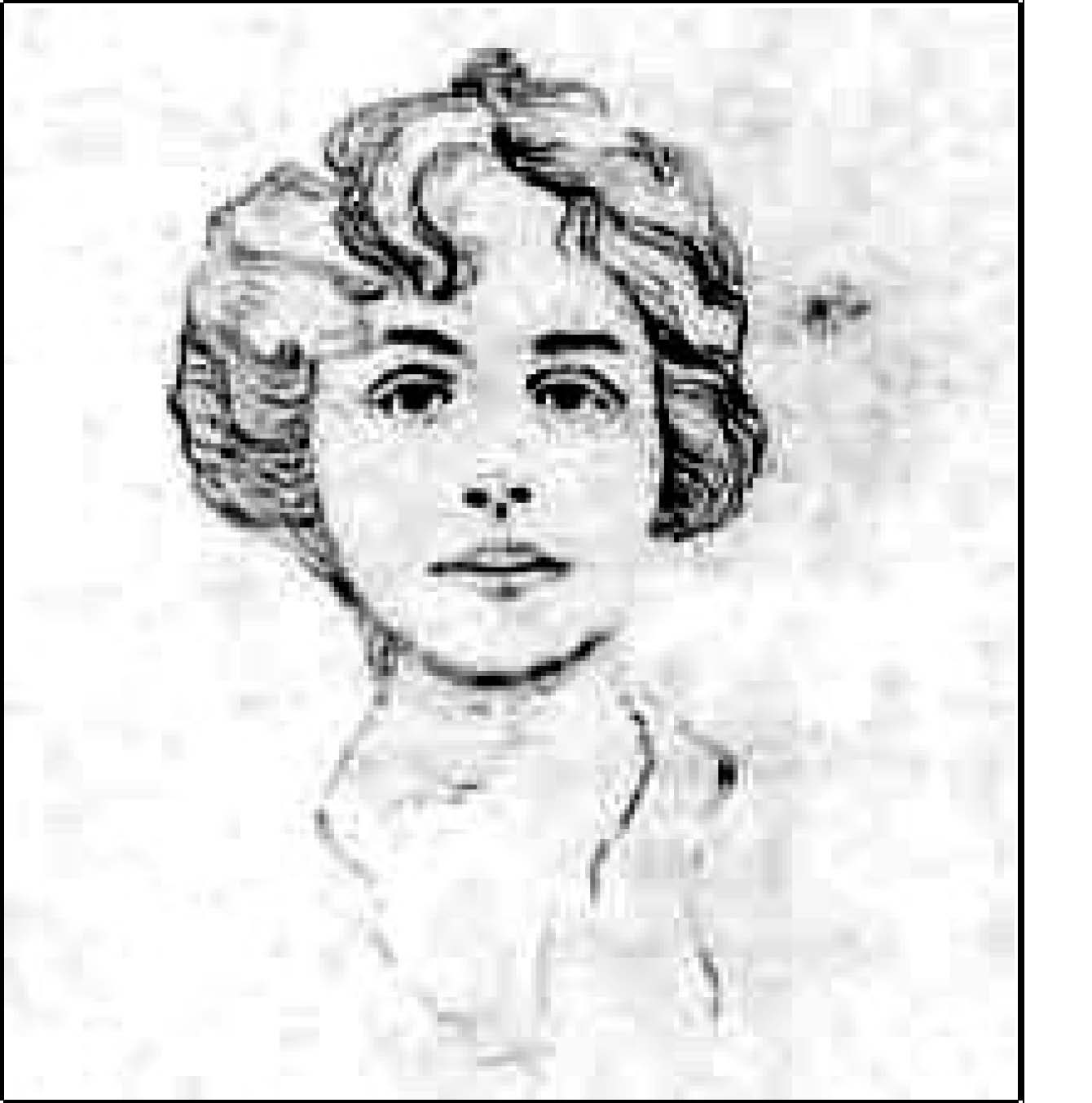

The remaining person in the picture had to be from an earlier generation. After much examination we decided that it was Elizabeth Watson, who had married Valentine Knight, Anthony’s father. Elizabeth had been born in 1802 so that in the photo she would be 92 years of age. We thought that she did not look that age; Using digital techniques on my computer I refined and magnified her face from the photograph and examined her eyes and the loose skin under her chin: Yes, I decided, she could be 92 years of age. Henry and Rosemary concerned themselves with the shine on her “hair” : was it her hair, or something else? They discussed her clothing style. The outcome was that everything pointed to her being whom we thought. Elizabeth died the following year in 1895.

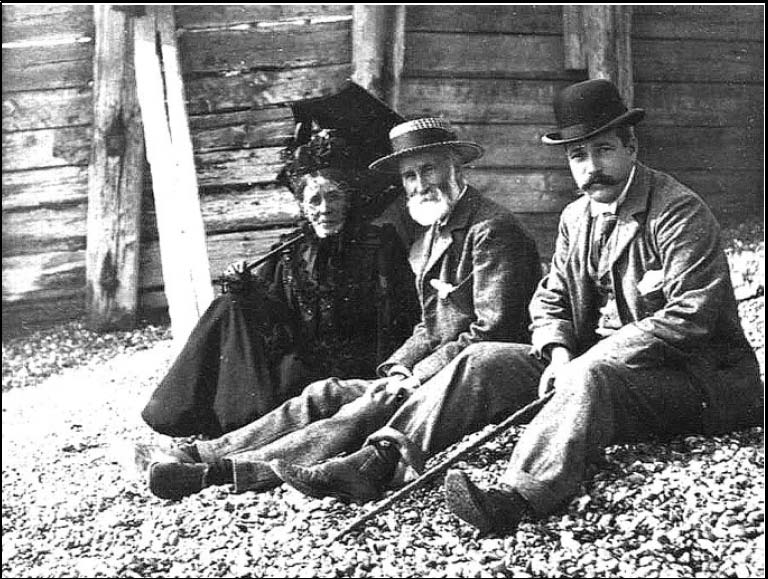

Andy found one other photograph in the attic which seemed to clinch the matter. It was a photo of Herbert Rumble sitting on the beach with an older couple. The man was clearly the same person as in the “Four Generations” photo - so we presumed it was Anthony Knight.

1

http://www.rpyc.com.au 2 Fall, John: The Rumble Family Register, 1994 Privately published

THE MYSTERY OF THE ‘FOUR GENERATIONS’ PHOTO

8

The woman with him we thought would be his wife Letitia. When I looked at the photo I saw a strong resemblance to my own mother, Dorothy Rumble. Henry Knight also noted family resemblances to ‘Letitia’ in the beach scene. He remarked: ‘I can see my niece Karen Jakobsen looking straight at me.’

Letitia Knight (nee Hochee), Anthony Knight & Herbert Rumble

Henry Knight also saw resemblances in the ‘Four Generations’ photo. He wrote:

‘Four generations’ has caused much excitement across the land.... We are convinced that the older lady on the left is Elizabeth Knight, the man her son Anthony Knight, then Mary Georgina and Lottie. We have compared heads of the man with Anthony's grandson Ernest St John Knight and find great similarities. Also to my father. The picture was taken at Vanbrugh Terrace, Blackheath, 4 days before Henry St John Knight married Ellen Theresa Glanville on 5/7/1894. My father used to say that Elizabeth travelled to Blackheath from Eastbourne in her 90's 'on a bus'. She died the following year. It all fits.

I already had some information from my earlier researches:

Elizabeth, the daughter of William Watson, was probably born in 1802. She married Valentine Knight on 13 December 1823, and died on 10 March 1895. This information was in an old diary found by Henry St.John Knight at No.2. Vanbrugh Terrace, Blackheath, London, when Letitia Knight died in 1920. Henry St.John Knight wrote to his sister Kate giving this information. Part of the letter is in the possession of John Fall.3

3extract from Fall, J: The Rumble Family Register page 116

THE BACKGROUND HISTORY OF THE KNIGHTS

9

10009 Valentine Knight b1722 Sp. Ann | 11010 Valentine Knight b? Sp. Mary | 12030 Valentine Knight b 1792 Sp. Elizabeth Watson b1802 | 13007 Anthony Knight b 1831 Sp. Letitia Hochee b 1834 | 14004 Kate Knight b 1866 Sp. Harry Rumble b 1866 | 15016 Dorothy Rumble b 1900 Sp. Victor Fall b 1902 | 16021 John Fall b 1928 Sp. Kathleen Melson b1926

The abbreviated chart on the left shows the line of descent from the earliest known member of the Knight family down to myself. Anthony Knight was my great-grandfather, but we know of three generations before him - and in each case they were named ‘Valentine’4. Much of our information stems from the research of Alexandra Knight, the elder daughter of Henry.

Alexandra discovered that Valentine Knight [10009] was born around 1722. He was apprenticed to Hugh Davis on 1 August 1739 to learn the trade of leatherselling. He was made a Freeman of the Leathersellers' Company by Servitude on 1 August 1749 and was admitted to the Livery in 1760-1.

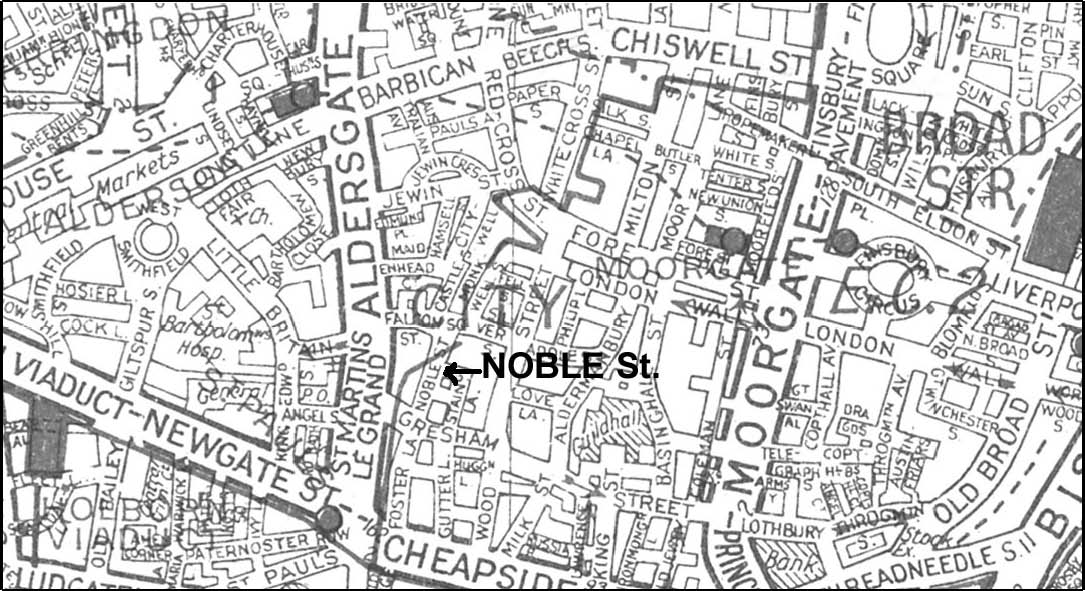

By this time he was married to Ann, of whom we know nothing, and he later became a jeweller in Foster Lane, off Noble Street, London. He died in February or March 1769.

We know that Valentine and Ann had a family, but only know the names of two children - Valentine [11010] and Robert.

Noble Street is near Cheapside and Aldersgate Street in central London, as marked in the map above.5

Because many people in families are given the same name - for example, there are three ‘Valentine’ Knights in the chart above, I have associated a unique ID number with each person to avoid confusion. T he first two digits represent a ‘generation’ number (arbitrarily 16 for me, 15 for my parents, and so on). The next three digits give a ‘family’ number within that generation. I first adopted this for the 1994 Rumble Family Register.

5 This map is taken from a 1958 London Street Directory

The above is a typical London street not far from Noble Street, in the 1800s

This is Cheapside, also not far from Noble Street, but about 100 years after the time of Valentine Knight

If it were not for further research in 2004 by Alexandra Knight, the above would be the sum total of our knowledge of our first Valentine Knight. However, Alexandra gained access to the Internet website6 of the Old Bailey7 in London and searched for ‘Knight’. She discovered the transcript of a trial in which John Andrew Martin stood trial for theft and burglary of the Knight’s home on 17 October 1768. The transcript lists Valentine’s wife as Mary, although Alexandra’s records show her as Ann. The transcript commences with:

John Andrew Martin was indicted for breaking and entering the dwelling-house of Valentine Knight , on the 17th of Oct. about the hour of two in the night, and stealing seven pair of snam-garnet gold buttons, value £6. 6 s. six pair of garnet ear-rings, set in gold, value £3. [a very long list of items stolen follows]8

Following this list, an opening statement was made by Valentine’s wife, the first part of which, follows:

I am wife to Valentine Knight, we live in Noble-street, Foster-lane, he is a jeweller. On the 18th of October last, I was alarmed about three in the morning; our bell rang, we lissened to know what was the meaning; I heard a person run up stairs. Mr. Reynoldson, that lodges in our house, call'd, and said, he believed there were thieves in the house; he came down into my chamber and took the keys, and went down stairs.

I followed him immediately after; my husband was ill in bed; and is so ill now he cannot attend the Court. When I came into the parlour, I found the flap of the cellar window was torn up, and a padlock torn from the cellar door, that opens into the street upon the cellar stairs; the door shuts on the flap, and was padlock'd on the inside. There is a window seat like in the parlour, which was a head-way front, the top of that was wrench'd off, and the top of it lay upon the ground; by that means a passage was opened into the parlour, close to the bureau where our goods were locked up: I locked them up myself, about eleven o'clock over night; I am always the last up, and know the cellar door and flap were safe at that time. . . .

Various witnesses were called and some of the stolen items were recovered. Martin was also accused of fourteen other indictments against him for burglaries, and he had been tried twice previously for other offences.

The transcripts gave a simple verdict: GUILTY - Death.

Hanging was, in those days, a very public affair, as illustrated by Hogarth on the next page.

6 Website: ww w. oldbaileyonline. org. John Andrew M artin 7 December 1768, The Proceedin gs of the Old Bailey Ref: t176812 07-9

7 The Old Bailey was the Central Criminal Court in London

8 The full transcript is given in Appendix 1 - page 296

Up until 1783 Tyburn Hill was the principal place of execution of criminals. This drawing by William Hogarth (1697-1764) is typical of the scene faced by Martin at his hanging

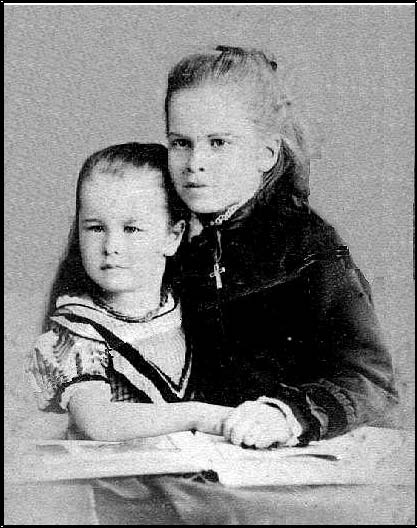

Before we examine the son and grandson of our first Valentine Knight, I will pause to look briefly at some pictures from the family album:

Mary Knight [14001AF]

Mary Georgina Knight, born in 1872, was the younger sister of my grandmother, Kate. She appears in the “Four Generations” photo on page 4, and in the family chart on page 6. She married Herbert Rumble in 1891 and had five children of whom Lottie Georgina, born in 1893, was the first.

Herbert, always known as Bertie, trained as a mechanical engineer. In1897 he was working in Buenos Aires while Mary and her children lived at her parents’ home which, by then, was at 2 Vanbrugh Terrace, Blackheath, London.

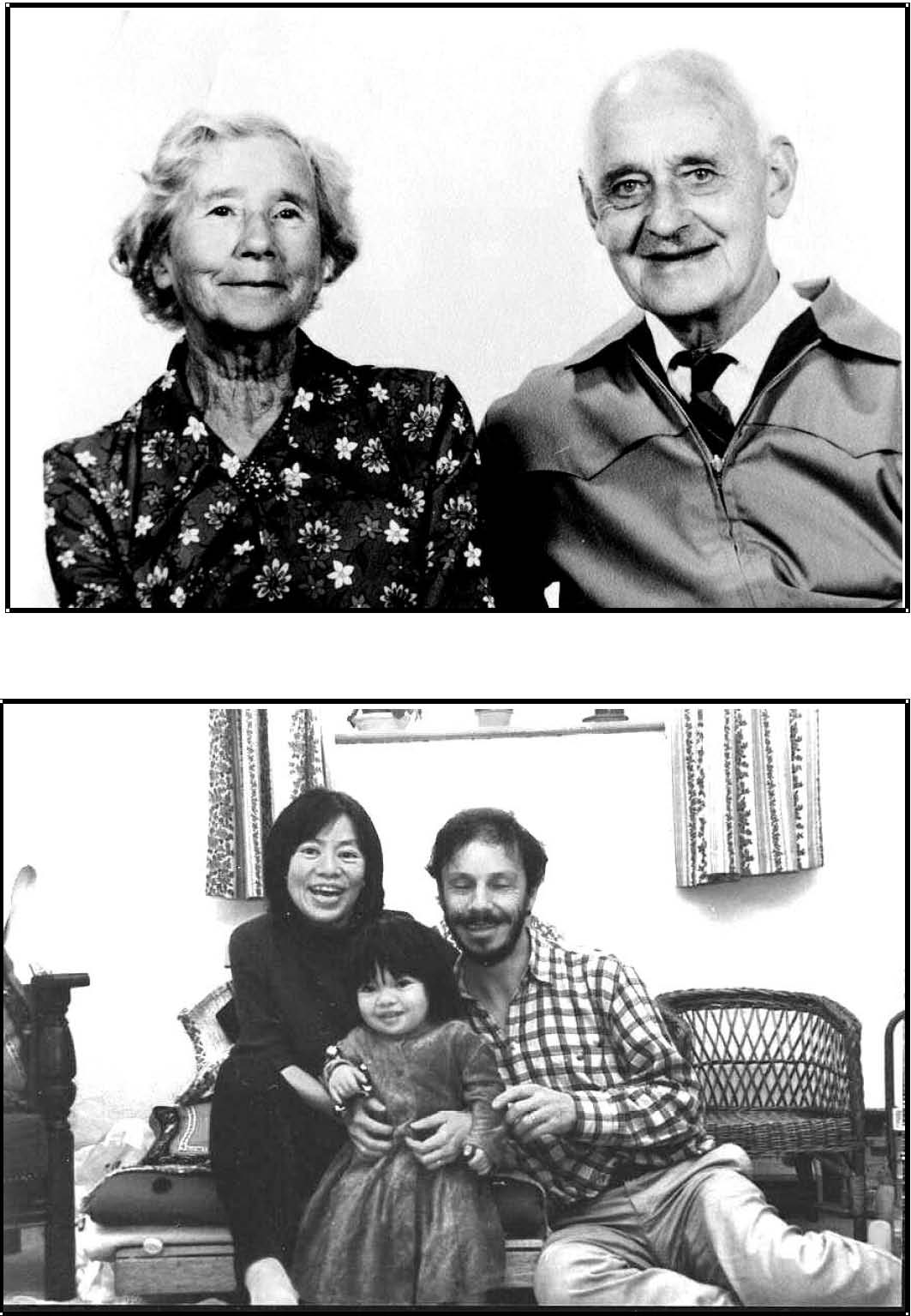

Little Lottie Rumble (page 4) grew up and married Herbert Graham Williams in 1921. They are shown in later years in the photo on the left. They were Andy Williams’ grandparents.

Kay-Yin, Maya & Andrew Williams

Those who contributed to research on the Valentine Knights are shown here. Above, Andy Williams and his family in February 2002 and, on the right, Henry Knight [16078] with Guy Duncan [16146] - who will enter our story when we explore our Chinese connection.

Henry

Knight & Guy Duncan

Henry

Knight & Guy Duncan

We know very little about Valentine [11010], the son of Valentine and Ann Knight. He was probably born in 1754. His brother, Robert, was apprenticed to learn the art of engraving, while on 13 January 1767, Valentine was apprenticed to Richard North, a Goldsmith of Lombard Street. Lombard street, not far from Noble Street, was in the hub of the City of London, and became a famous banking area. It derived its name from the Lombards, merchants, money-lenders, and bankers who settled there in the twelfth century from Genoa, Venice and Florence. The Lombard street of today probably bears little resemblance to the street towards the end of the eighteenth century because at that time six famous streets: Threadneedle Street (of Bank of England Fame), Cornhill, Lombard Street, Wallbrook, Poultry and Princes Street all converged in this area, but extensive changes were made in 1831 when buildings were pulled down and two new streets created.

Valentine became a Freeman of the Goldsmith’s Hall by Servitude on 1 February, 1775. Both he and his brother Robert eventually became jewellers in Noble Street. We know that Valentine married Mary and that they had a son - also named Valentine [12030], but we do not know if there were other children, nor when he and his wife died. 9

It is a very different matter with the next Valentine. He made quite a name for himself and much is recorded about him. He was born in 1792 in London and was baptised 1 January 1793. We know little of his very early life but first hear of him when, on 5 December 1821 at the age of 29, he became a Freeman of the Goldsmith's Hall by Patrimony10. Two years later, on 13 December 1823, he married Elizabeth Watson, the daughter of William Watson a watch-case maker at St.James, Clerkenwell. Between 1825 and 1843 Valentine and Elizabeth had ten children.

Initially the family lived at 4 Newcastle Place, Clerkenwell Close, where Valentine had recently set up as a goldsmith specialising in engine turning - a process for producing symmetrically patterned engravings. He found a substantial demand for engraved gold and silver dials for clocks and watches and pursued this line of business in particular. The business flourished due to Valentine' s dedication and the high quality of his work. He died on 17 November 1867 in his 75th year. His wife survived him, to die at the age of 93 on 10 March 1895. Both were buried at Highgate cemetery.

9 Research by Alexandra Knight [17149]

10 When discussing the Valentine Knights, two words - Servitude and Patrimony - have been used. Patrimony is something inherited from one’s father or ancestors. If one’s father was a goldsmith and his son follows him into the trade, then he gained entry to the profession by patrimony (or by inheritance). If one’s family was not already in the profession, a young person could become an apprentice to someone in that profession and eventually gain member ship ‘by servitude’. Strictly, servitude is a condition in which one lacks liberty to determine one’s way of life

THE THIRD VALENTINE KNIGHT [12030] - A SELF-MADE MAN

15

Brenda Rohl11 visited this cemetery in 1989 and gave the following account:

Highgate cemetery is the most amazing place; very Victorian!! I had to walk up the "Egyptian Avenue" and around the "Circle of Lebanon" where the crypts are. The poor Knights seem like the paupers on the block!! The grave is mottled brown marble and is only about knee height.

Among other things, Valentine became the Founding President of the British Horological Institute and their Journal published on 1 December 1867, contained an obituary that gives an excellent insight into his life and standing in the community:

With deep regret it becomes our sad duty to record the death of Valentine Knight Esq., President of the British Horological Institute, which happened on the 17th November, 1867, at his residence, Thorncroft, Leatherhead, in Middlesex. He was in his 75th year, but until lately was hale and active, having a much younger appearance.

Valentine Knight was essentially a self-made man. The scene of his earliest life was in Newcastle Place, Clerkenwell Close, where for many years he conducted a flourishing business as gold and silver dial-maker and engine-turner. For some years before quitting the business, he joined partnership with Mr Burr. He was renowned for the style and excellence of his work in the palmier days of watch making, particularly for his success in the color of his dials. At the annual dinner of the Institute in 1863, he said of himself, in the genial manner peculiar to him :-

“I have always felt a deep interest in the welfare of Clerkenwell, and I hope I shall always continue to do so. At an early age I set up in business in it, in the engine-turning and gold-dial departments. I happened to have a very lucky rise. I chanced to make an article in the gold line, such as I believe I may say with truth was equalled by no other person. When Americans came to Coventry or London to give orders for watches, they almost always insisted upon having Knight's dials. That was a very great advantage to me. To a certain extent I was a child of fortune. I succeeded much beyond my expectations. During many years I worked sixteen and eighteen hours a day, and sometimes all night. Such an enormous business I was sure could not last, and I therefore thought it better to make hay while the sun was shining. I did so, and at a comparatively early age was enabled to retire from business.”

11 Brenda [17033], born 1965, is the daughter of my first cousin Robin Furphy.

His retirement from the business in Clerkenwell, only however necessitated employment in other affairs for a mind so active and a head so clear as his.

He was one of the earliest directors of the Mutual Life Assurance Society, a flourishing association, which was the first (excepting the Amicable) to raise its claims to public support on purely mutual principles. Having its origin among Clerkenwell supporters, it is gratifying to know, the Mutual is one of the solidist institutions discharging the important functions of Life Assurance. Mr Knight's business habits led him to take a very active interest in those great works of modern times, railways, and his voice was often effectively raised at their public meetings against prodigal expenditure. After giving up his trade pursuits, Mr Knight filled for some years the office of Magistrate for Middlesex. He was elected to, and liberally and worthily discharged the duties of President to several trade institutions.

He was President of the Watch and Clock Makers' Asylum, to which he contributed generously. He was intimately associated with the Horological Institute from its very beginning, having been called upon by the Preliminary Committee to preside over the public meetings which they had called, and which took place at the "Belvidere Tavern," Pentonville, on the 15th June, 1858, having for its object the founding of the Institute. To that call he responded, and by his capital ability as chairman, and by starting a subscription list with his own cheque for ten guineas, he made an acknowledged success of that first effort.

When the institute had been organised, Mr Knight was unanimously elected to the honorable post of President, to which he has been year by year unanimously re-elected ever since. His lamented decease causes the first vacancy in the presidentship. At the Inaugural Dinner of the Institute, he said,

"Other countries might have carried the science of horology to a great extent, but

it would be a disgrace to Clerkenwell to be second to any nation under the face

of the sun in that art."

And he invariably insisted upon the claims of the Institute, not only upon the trade, but the public also.

He pronounced the Institute to be an association which was wanted for the honor of the country and the trade, to enable it to flourish as it ought to do; and he was sure that through its means, watchmaking would prosper.

THE THIRD VALENTINE KNIGHT [12030] - A SELF-MADE MAN 17

Although he considered himself an outsider of the trade, he should be happy at all times to give all the assistance to it which lay in his power, not only by personal attendance at its meetings, but by subscribing to its funds, and assisting it in causing it to prosper to the extent which it so highly deserved. He felt deeply interested in horology, and had a high respect for every man connected with it, and should always feel pleasure in meeting them upon such happy and convivial occasions.

How faithfully he bore in mind and acted upon his promise, never swerving or becoming lukewarm, is well known to the members.

During his presidency, the British Horological Institute has been greatly indebted to him; firstly, for his great attention to the duties of his office, secondly, for his warm advocacy of the claims of the Institute to public support, but above all, for the great influence he possessed with all connected with horology whether immediately or remotely, this influence being constantly exerted to expand the Institute and its funds, while few could withstand the solicitations of one so generally beloved.

His social position was eminently conducive to the success of his kind intentions. He had retired from business in Clerkenwell long enough to prevent even the memory of trade jealousy to remain, even if he had ever exhibited any, which is very doubtful, for he was personally of an excellent presence, a very amiable temper, and possessed of a manner well calculated to endear him to those with whom he was brought into contact. He was, without exception, the most liberal supporter of the Institute, took the warmest interest in it, and made it a point of honor and duty to assist whenever his services were required, or he could aid it by his influence. Whenever it was necessary to confer with him, upon the affairs of the Institute, he was always a ready listener, and from his great and varied experience, and good judgement, he was an excellent counsellor.

At the anniversary dinner in 1861, he stated modestly, but how truthfully his conduct has always shown;

"I shall never deem it a condescension on my part to do what I possibly can to promote the interests of any society which tends to the welfare of the parish of Clerkenwell, and more particularly to the watch trade. Having spent many years of my life within that district, and having taken some money out of it, I should be ashamed of myself if I looked back without having a feeling of kindness and good fellowship towards those with whom I was formerly associated; and until the last day of my life I assure you that I shall have very great pleasure in forwarding the interests of all the societies connected with the parish."

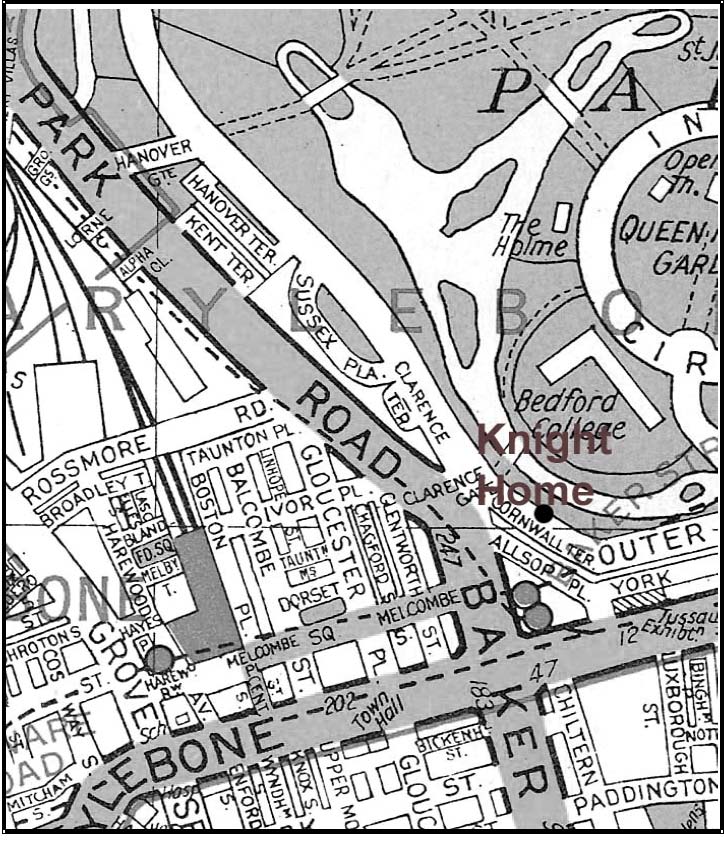

Valentine Knight lived at No.3 Cornwall Terrace, Regents Park, London (above) from about 1840 to 1860. No.3 is just to the left of the four round columns on the right side. The first floor half-round window belongs to it

Valentine finally retired to Thorncroft, Leatherhead, Surrey (formerly, Middle

sex) - as shown above

THE THIRD VALENTINE KNIGHT [12030] - A SELF-MADE MAN 19

At the anniversary dinner which took place this year he said he was fast getting into the sere and yellow leaf, but as long as he lived and could appear before the members of the Horological Institute, nothing would give him greater pleasure.

Those who heard these words little thought how soon he who uttered them would be lost to them. Peace be with him! Clerkenwell will long remember him, self-made men, yea all men, might well have imitated his happy disposition, and geniality of character.

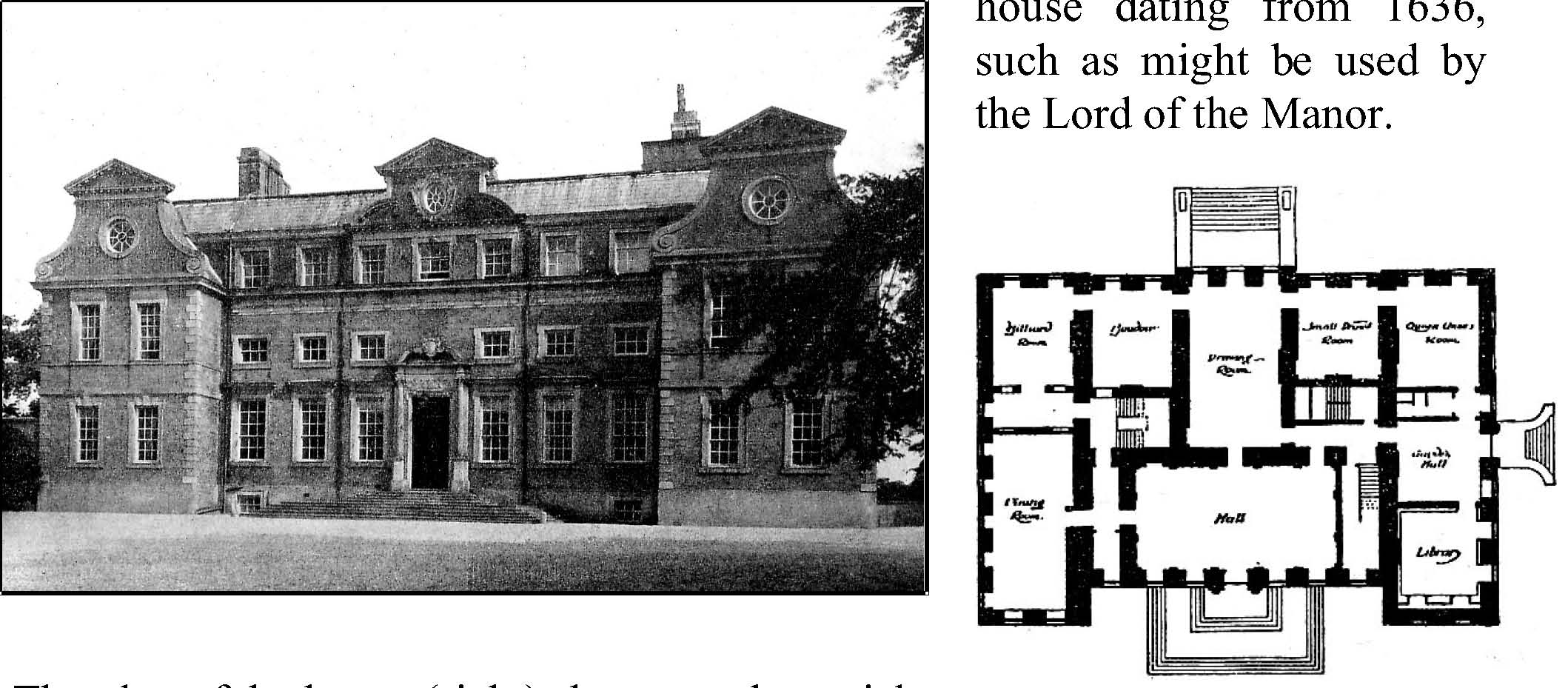

Before his retirement in 1851, the family had moved to number 3 Cornwall Terrace on the Outer Circle of Regents' Park, near the top of Baker Street. They later moved to Thorncroft, an elegant country manor, built in the 1770's, on the outskirts of Leatherhead, then in the county of Middlesex, but now in Surrey. There had been a house on this site since before Domesday and it held one of the two Manorial Courts in the area. The house still stands today but is used as offices.

While we know much of Valentine, we know little of his wife Elizabeth. In her Will, dated 1882, she left her house for her son William to occupy for three years after her death with the option to purchase it for £4,725 stg. Otherwise the house was to be sold and the proceeds then became part of her estate, which was divided equally amongst her children. In 1882, a house of this value, must have been substantial. She also refers in her Will to marble busts of herself and her late husband by E.H. Baily, the man who produced the Statue of Nelson in Trafalgar Square, London.

As

a small aside to this, in February 2005, Henry Knight [16078] wrote:

As

a small aside to this, in February 2005, Henry Knight [16078] wrote:

My daughter, Alexandra, rang rather excitedly to say that Sotheby's, the auction house, was selling a bust by EH Baily just listed as a 'Gentleman 1843'. We reckoned that the features were reasonably closely aligned to various members of the Knight family and by rough science estimated that there was a 1 in 4 or 5 chance that it was Valentine. So we went to the auction. Lot 99 quickly came under the hammer and the auctioneer uttered the words ‘possibly Palmerston’12

I made my bid according to plan and pushed the price well beyond the pre-auction estimate but let it go to a telephone bid when it looked like becoming an expensive investment. As for Valentine Knight, he may still be out there somewhere.....

12 Former Prime Minister and Foreign Secretary of Gunboat Diplomacy fame.

As is shown in the chart on the preceding page, Valentine and Elizabeth Knight had ten children. We know only a little about their children except for Anthony:

Valentine Catherwood Knight was born in 1825, matriculated to University College in 1844, graduating in 1848. He was called to the Bar, Inner Temple, in 1850, and later became curate at Pucklechurch, near Bristol. He died on 28 August 1876 near Boulogne, France.

Elizabeth Knight was born in 1826 and married William Atkinson Langdale in 1857 being his second wife. William was the fourth child of Marmaduke Robert Langdale and Louisa Jordan. He was born on 6 November 1818. There is an entry for him in The Landed Gentry which stated his address as Ladbroke Square, London. He had four sons by his first marriage; after his wife died, he married Elizabeth. He died on 30 October 1874.

William Watson Knight, the third child, was born in 1828 and remained a bachelor. He died at Eastbourne on 16 April 1893

John Watson Knight, the fourth child, was born on 10 March 1830. We know very little about him except that he married, and that the 1895 marriage certificate of his son John Aubrey shows his father as a witness and describes him as ‘Gentleman’ - in those days this word would have indicated that John was a member of the Landed Gentry.

The next child was Anthony, my great-grandfather. We will leave him to last.

Frederick Knight was the sixth child. He was baptised on 4 March 1834, became a member of Her M ajesty’s 69th Regiment and died at the age of thirty on the 8th June 1864 at Marylebone.

Charlotte Russell Knight was the seventh child, baptised on 13 May 1836. She married William Hill, later Lieutenant-General of Her M ajesty’s 2nd West India Regiment. They had a son, Valentine Hill [14097]. We only know of his existence through the Will of his grandfather Valentine Knight [12030], which stated:

I direct that twelve months after the death of my wife five hundred pounds shall be invested in lieu of her lapsed income for the benefit of my grandson Valentine Knight should he then be living to be paid to him with accumulations at the age of 21. In the same way two hundred pounds to my grandson Valentine Hill.

Katharine Knight the eighth child was baptised on 6 December 1838. Her marriage to Arthur Drinkwater Bethune Chapman is shown in the December 1881 records for the parish of Eastbourne. My grandmother, Kate Knight [14004] received a letter from Arthur on 5 May 1919. This was probably not long after Katharine’s death. It is interesting to note that a former owner of Thorncroft, the elegant country manor to which Katharine’s parents retired, was a Colonel Drinkwater Bethune.

Henry Knight, the ninth child was born on 13 June 1841. He matriculated to Brasenose College in 1860. We know nothing more of him.

Alice Mary Knight, the tenth and last child was born on 27 July 1843. She married the Reverend Henry Vincent Shortland as noted in the July 1881 quarter records of the parish of Kensington.

Anthony Knight, my great-grandfather, was born in London on 24 October 1831, being the fifth child of Valentine and Elizabeth Knight. He married Letitia Hochee at Lingfield, Surrey, England on 1 August 1861 and died on 25 May 1912. They raised six children, as shown in the chart, above.

My mother, Dorothy Rumble [15016], always romanticised about her ancestors. When I was very young, she told me that Anthony was a very rich man who had no need to work for a living. He dabbled, she said, on the stock exchange, implying that this was simply an amusing, gentlemanly pursuit. She also said that his wife, Letitia Hochee, was the daughter of a rich Chinese man, Ho Chee, who had married a young seventeen year old English girl. She said that Ho Chee may have been the Chinese Ambassador to Britain

- but, whatever he was, she implied that he was of high social status.

Anthony and Letitia, she told me, were so rich that they travelled to New Zealand with all their family and servants and that it was in Christchurch that my grandmother, Kate Rosaline Knight [14004] was born. I was also to discover that, at the time, there was no Chinese Ambassador to Britain, and that Anthony’s life was not exactly as my mother imagined but, before we look at Anthony and Letitia’s life, we will examine the Chinese connection, alluded to at the start of this search13.

13 See page 5

When my mother died in 1988 I found amongst her papers the addresses of English relatives with whom she corresponded. These were all on the Rumble side of the family, so I wrote to them. Over a period of time they gave me much information about my Rumble ancestors but at that time I had no contacts for the Knights.

One day, amongst my mother’s papers, I came across a small hand-written family tree in which the name of Ho Chee appeared. Against this was written “From Oxford University. ” I decided to follow up this scrap of information as I had a contact at Oxford.

Brenda Furphy, My first cousin, removed by one generation, had married Andrew Rohl, and Andrew was now studying for his doctorate at Oxford. I wrote to

Brenda and asked if she could look at the records of Oxford University to see if there was any men-

tion of our Chinese ancestor. I knew that he could not be a Chinese ambassador to Britain, as my

mother had hinted, but there might be a connection with Oxford. Brenda checked Foster’s Alumni

Oxonensis from 1715 to 1886 without success. However, Brenda became interested in my project and, not

working or studying at the time, decided to undertake research for me. She wrote that she had applied for a birth certificate for Ho Chee’s daughter, Ann (13038), whom she had discovered in the Records Office. Birth certificates usually show the occupation of the father, so we hoped to find something about Ho Chee from that.

When the certificate arrived, he was simply classified as “Gentleman” which probably meant that he owned landed property. However, the certificate also showed a place-name in 1840 as “Nortons, Lingfield”. From this Brenda consulted census and other records and slowly built up a picture of him. She applied for many birth, marriage and death certificates, obtained photocopies of Wills, and visited cemeteries. The search for Ho Chee and his family became a combination of detective work and jigsaw puzzle. We had false leads, and sometimes misinterpreted the information we received.

Brenda found the Will of Charlotte, the wife of John Hochee14, as he became known. This referred to an oil painting of our Chinese ancestor. We became even more determined to persevere with our research.

14 In C hina the custom is to place the family name before the giv en name , whereas it is the other way around in Britain. To avoid him being referred to as Mr Chee in Britain, the two names were joined as a single surname Hochee. He then acquired the given name, ‘John’ probably after his benefactor, John Elphinstone -as we shall see later.

Then we obtained copies of his 1839 letter to the Government applying for “denization”15. In this he wrote:

“I have reason to believe I should come possessed of freehold landed estate. . . if

the disability of my being alien born were removed by Letters of Denization. . .”

How was he to gain possession of freehold estate? We did not know.

Next, we discovered details of his other children and found that his first son was baptised John Elphinstone Fatqua Hochee. Where did the name “Elphinstone” come from? Was it the maiden name of an ancestor on his mother’s side? Eventually we discovered that that name was “Milton”, and that in later life this son was known as John Milton, not as John Meredith, as my mother had once told me. “Elphinstone” remained a mystery.

Before I started my search, there was much confusion over the number and names of John Hochee' s children. Dorothy Fall knew of two daughters, Letitia and Florence. She said there was also a son who became a captain in the army and changed his name to Meredith as he did not like the Chinese name. Further information was given by Anton Knight (15020), grandson of Letitia Hochee and Anthony Knight. Anton was brought up for most of his childhood by Letitia.

In a letter to Dorothy Fall he omitted the names of Florence and Meredith, but added Annie and Netta Hochee. Henry St.John Knight (14015) in an 1897 letter to his sister Kate (14004) stated that "Elphin Hochee married on 20.2.1895," also "Uncle James Hochee died at Finchley at the end of 1896."

At that stage I had such flimsy material to work on. We now know that Florence (14095) was the granddaughter, not the daughter of John Hochee, being a child of his son James (13008). We also know that John Hochee' s other son, John Elphinstone Fatqua Hochee (13009), did indeed become an officer in the army but changed his name to Milton, not to Meredith. The Elphin Hochee who married in 1895 was found to be John Elphinstone James Hochee (14088), the first child of James Hochee. "Netta" was Henrietta (13039). I was still much confused.

And then, one day I received a letter from Brenda: she had made an important breakthrough. She had made contact with a Henry Knight16 (16078) and his daughter Alexandra (17194). Henry Knight’s grandfather had been Henry St. John Knight (14015), my grandmother Kate’s brother. Henry (16078) was ten years younger than me and was my second cousin. Henry and his daughter Alexandra had already researched both the Knight and the Hochee families. They knew where the portrait was located, and they knew the significance of the name “Elphinstone”. I contacted Henry and Alexandra, and soon I had in my hands a copy of the research written up by Alexandra.

A major part of this is presented on page 27:

15 Denizen = an alien admitted to residence and to certain rights of citizenship in a country.

16 See chart on page 6

JOHN AND CHARLOTTE HOCHEE AND THEIR CHILDREN

Our

first pictures of John Hochee and of Charlotte ( née) Mole The

portrait of Hochee is in the hands of the Seel family (See page 6)

Our

first pictures of John Hochee and of Charlotte ( née) Mole The

portrait of Hochee is in the hands of the Seel family (See page 6)

OUR

FIRST HISTORY OF JOHN HOCHEE 27

OUR

FIRST HISTORY OF JOHN HOCHEE 27

Ho Chee was born in Canton, China, in 1789 during the Qing (or Manchu) dynasty. Very little is known about his life except that he was the son of Ho Foo, a mandarin. The family lived at Hyan-Shan in Canton (now known as Guangzhou in the province of Guangdong) and were landowners. Mandarins were the qualified Government officials and Ho Foo may have been dealing with trade matters, the chief occupation of Canton, which brought him into contact with the East India Company. At this time Canton was a major trading post for the company in China; the East India Company had large tea factories in Canton and had a lucrative and flourishing trade there.

The history of this company in helping to open up China to Western trade is of some interest. With the coming of the industrial revolution, Britain' s need for raw materials at home, and markets for manufactured goods and investments abroad, induced that country to take the lead in “opening” China. This was accomplished ultimately by war, in and after 1839, consequent upon more than two centuries of peaceful relations.

Attempts at establishing relationships were made from 1635. The Chinese emperor Ch’ien Lung (1736-96) commended George III for his “ respectful humility” in sending a “memorial and tribute.” The request that an English envoy be permitted to reside in Peking was refused, it being disclosed that China itself had no desire to be represented abroad. Ch’ien Lung’s official wrote, “As your Ambassador can see for himself, we possess all things. I set no value on objects strange or ingenious, and have no use for your country' s manufactures. ” China' s goods, however, are “ absolute necessities to European nations”; therefore, “as a signal mark of favour” trade might be carried on at Canton - but not, as the English had asked, at “Ningpo, Chusan, Tientsin and other places . . .,” including storage of goods at Peking.

Having dispatched to China an envoy whose conveyances inland bore flags marked “ Ambassador bearing tribute from the country of England, ” and who presented gifts (“ tribute”) to the imperial court even though he did not perform the kowtow, Britain was definitely rated as a vassal kingdom.

For almost half a century, despite increasing friction over impositions and limitations upon its trade, England maintained peace with the Manchus and their subjects. It was during the Anglo-Chinese wars of 1839-42 and again 1856-60 that Britain took the lead in challenging Manchu-Chinese pretensions to “sway the ten thousand kingdoms,” and in insisting upon recognition by Peking of the western state-equality concept.

Another cause for friction leading to the Anglo-Chinese wars was the opium trade. Foreign, as opposed to native, opium was imported into China first by the Portuguese but later by other westerners. Until April 1834, the East India Company held a monopoly on English trade with China. The Company began farming out opium in Bengal in 1773, in which year the drug was first imported through Calcutta into Canton. Determination of the West to have Chinese teas and products; small demand by the Chinese for western products, including English woollens; unwillingness of the English to pay for Chinese goods with silver bullion; the high value of opium and its popularity for smoking; all these explain the phenomenal growth of the opium trade despite Chinese imperial anti-opium edicts from 1729. These edicts were disregarded by native officials and non-officials and aliens alike.

This opium trade may have triggered the wars beginning 1839, but the conflict was basically one between two worlds and two different concepts of international relations.

It would appear that it was through the East India Company that Ho Foo and his son Ho Chee met John Fullerton Elphinstone, eldest son of the Hon. William Fullerton Elphinstone, one of the directors of the company. John Elphinstone was a "Supercargo" in Canton, responsible for managing the sale of goods.

Perhaps Ho Chee and Elphinstone came into contact through their work and became close friends. Elphinstone returned home in January 1816 arriving around April/May 1816. Local stories in Dormansland17 say that Ho Chee accompanied Elphinstone to England when he became ill, and East India Company records confirm that Elphinstone was indeed prone to ill health. However, we now know from Ho Chee' s application for denization that Ho Chee did not arrive in England until August 1819.

Although Elphinstone had fully intended to return to China, he had retired from the East India Company in 1818 due to ill health. The following year we find Ho Chee arriving in England. We can only speculate as to the reasons, but it appears to have been due to their close friendship. This is possibly not the whole story for his coming. Ho Chee was undoubtedly able to speak English and with his knowledge of China and its customs he would have been particularly useful to a merchant such as Elphinstone and the East India Company connections. It is also known that George III had been keen on establishing diplomatic relations with China and Ho Chee's advice via the East India Company could have been valuable in this respect.

No love was lost between the English and the Chinese; the official term for the chief of the supercargo’s council was “Red-Haired Devil, ” and all Englishmen were known as “ Red-Haired Devil’s Imps”. In view of this, it is remarkable that Ho Chee and Elphinstone should have become friends. The following extract from “Lords of the East - The East India Company and its Ships” by Jean Sutton, shows the lack of understanding and distrust between the English and the Chinese at that time:

“These seemingly innocent articles in the officers' private trade - generally termed ‘sing-songs’ - bedevilled the company's trade with China for a hundred years. The Emperor collected them, and so they were highly sought after by the mandarins for bribing their superiors. On the slightest pretext, the mandarin in charge of the customs, the ‘hoppo,’ stopped the trade, threatening the company with huge demurrage bills until a bribe, of which the ‘sing-songs’ constituted the most important part, was exacted. Extortion was facilitated by the system of trade with the Europeans. A handful of Chinese merchants, the Co-Hong, bought the right to a monopoly of the trade. Each member of the Ho-Cong was appointed a security merchant to a few European ships and dealt with every aspect of the trade with the ships' supercargoes and, later, the council of supercargoes resident in the season at Canton.

17 Dor mans Land, sometimes written as “ Dormansland” is the area in Surrey that includes Lingfield, where Hochee settled.

OUR FIRST HISTORY OF JOHN HOCHEE 29

It was therefore the security merchant who was forced to purchase the ‘singsongs’ to placate the 'hoppo.' Captain Wordsworth's chiming clock, at £150, was relatively cheap; the more sophisticated - with figures dancing minuets, jigs, and gavottes, birds singing and waterfalls cascading - were extremely expensive, frequently bringing the security merchants to the verge of bankruptcy and so threatening to increase the already unhealthy monopoly of the Co-Hong.”

The voyage from China to England was geared to the monsoons; outward journeys were normally only undertaken between April and September, and homeward between November and March. The larger ships (usually those of more than 1200 tons) were used for trade with China. The East India Company used ships of its own fleet, amongst which were ships such as the “Elphinstone” and the “Broxbournebury. ” The ships were necessarily fast journeys taking approximately four months - not only for trading reasons but also to outmanoeuvre pirate boats. They were also armed to ward off pirate attacks. Goods brought to England included fans, ivory carvings, lacquerware and porcelain. After 1700, tea was the major commodity as well as lead, cotton and silks. Commanders and officers were able to trade privately, and traded in sugar, bamboos and spices as well as other luxury goods.

The Amsterdam typica l of the sh ips of the day a lthoug h no t a ship belonging to the British East India Company

Braughingbury 175 acre Farm where Charlotte Mole lived until her marriage

Ho Chee and Charlotte were married on 6 January 1823 at St. Mary' s, Church

Braughingbury

OUR FIRST HISTORY OF JOHN HOCHEE 31

Ho Chee may well have had it in mind to return to China after visiting his friend but, presumably because of the close bond with John Elphinstone, decided to stay. He later became a naturalised British subject by denization (denization 1839; naturalisation 1854).

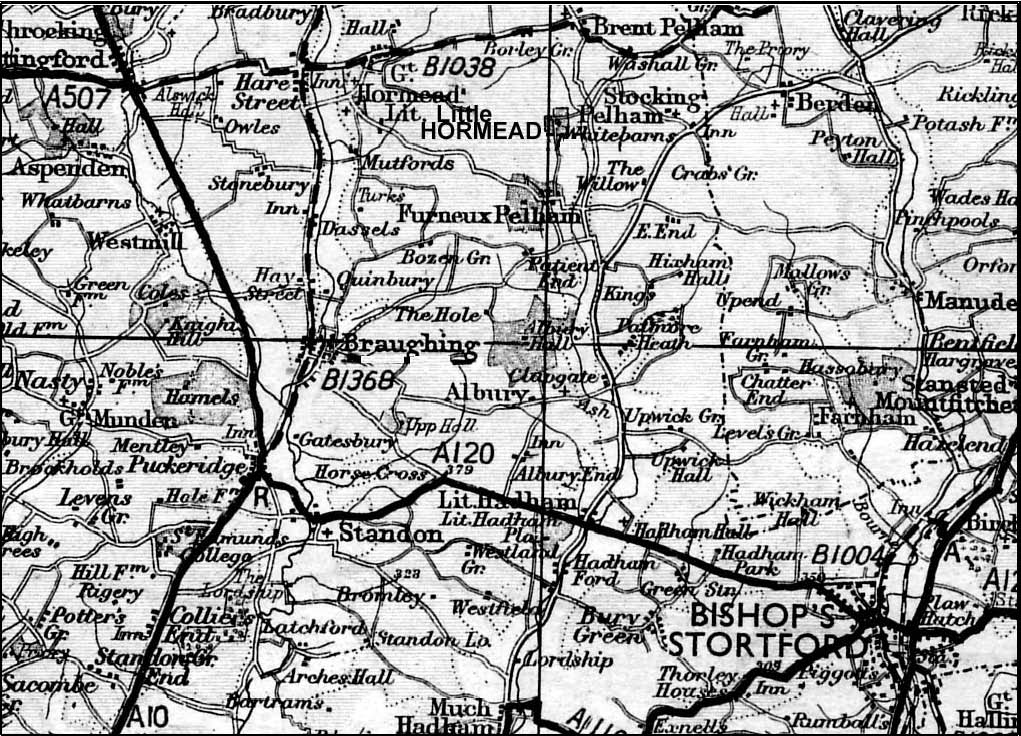

There is a short gap in our information here, but Ho Chee somehow found his way to the village of Braughing in Hertfordshire. We believe Elphinstone lived in or near the parish. It was here in Braughing that Ho Chee met seventeen-year-old Charlotte Mole (12003), the ninth child of Chamberlain Mole (11017) who rented Braughingbury Farm, covering approximately 175 acres.

Ho Chee and Charlotte were married on 6 January 1823 at St. Mary' s, Braughing, and they continued to live in the parish for another three years. Ho Chee gradually became known as John Hochee and Charlotte took Hochee for her surname. The following year their first child, Sarah [13051], was born on 7 March 1824, and she was baptised at St.Mary' s on 27 July the same year.

Early in 1826, John Elphinstone purchased Ford Manor, in what is now the village of Dormansland in the Parish of Lingfield, Surrey, but at that time numbered a few houses and surrounding farms. On 14 March that year, their second daughter, Henrietta (13039), was born at Braughing and they moved to Ford Manor with Elphinstone before she was baptised at the Parish Church of St. Peter and St. Paul, Lingfield on 30 July 1826. Dormansland and the Parish of Lingfield became home to the Hochee family and it was to remain so, for some time at least, into the next century.

On 12 June 1828, the Hochee' s first son was born and was named John Elphinstone Fatqua Hochee [13009], probably in gratitude for the help and friendship of John Elphinstone, who may also have been a God-father. It is also known that one of the Chinese security merchants in Canton was named Fatqua and may have been a relative. However, John Elphinstone Fatqua Hochee was not christened until May 1831 when he was baptised along with his year-old sister, Jane (13052). John E.F. Hochee later used the name John E. Milton, although this was probably not until after his father' s death. He later became a lieutenant in the Madras Army.

In 1831, Elphinstone purchased Nortons Cottage which he let to Ho Chee. It seems that a new house was built on the same site around this time. This house still stands although its name has been changed several times. It is an impressive building for the area; it has been described by a local historian as a “country house of quiet distinction.”

Their younger son, James [13008], was baptised in 1832. Letitia Charlotte (13007) (baptised 12 April 1835) and Ann Hochee (13038) (born 9 June 1840) followed. Their last child, Emily (13053), was baptised on New Year' s day 1845.

Only a year later, on 1 April 1846, their daughter Jane, died at the age of sixteen. She was buried in Lingfield churchyard, where she was to be joined, many years later, by her elder brother and her mother.

[This account continues on page 35]

Nortons “Cottage” as it stands today.

Described by a local historian as a “ Country house of quiet distinction”

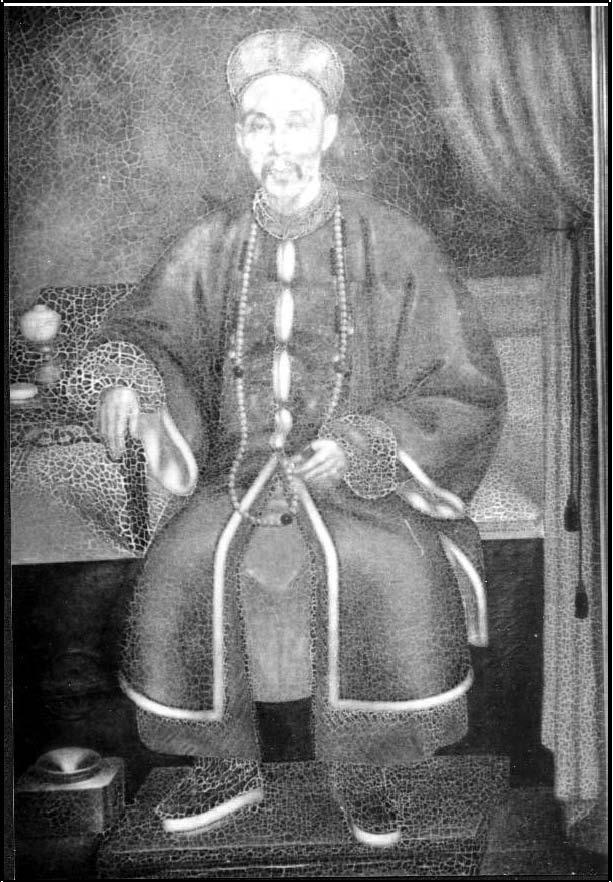

< This is Ho Foo.

Both John Ho Chee’s father and his nephew have been described with this name. Present day family members believe this portrait is of John Hochee’s father, but we cannot be sure -it may be his nephew.

This is a photo of the dining room at Braughingbury farm where C harlotte Mole grew up

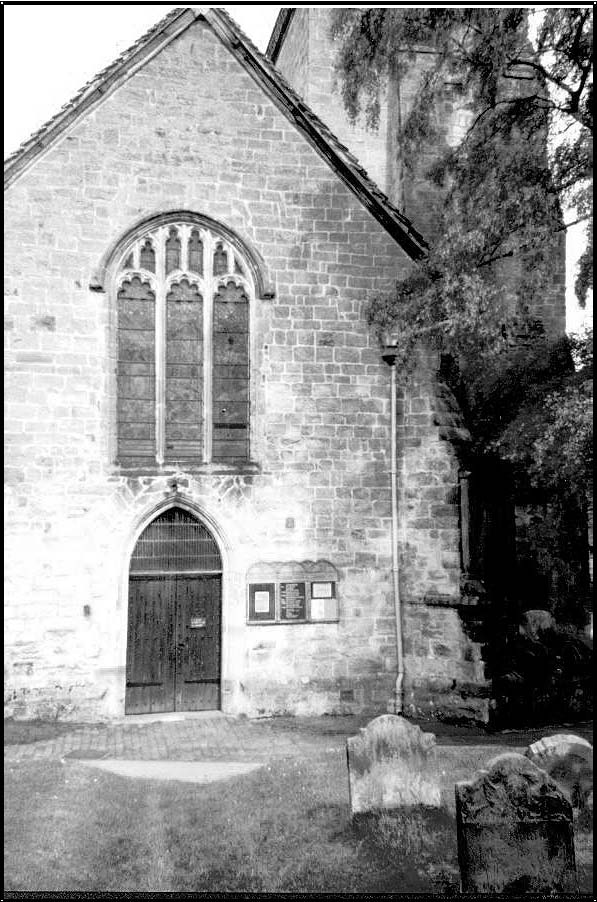

< The Parish Church of St. Peter and St. Paul at Lingfield.

Many members of the family were Christened there; others were married there, and some were buried there.

Although their second child, Henrietta, was born at Braughing on the 14th March 1826, the family moved to Lingfield and she was Christened in this church on 30 July 1826.

The photos on this page were taken from the book: Peter Morris-Jones: Family History18 Peter was a third-cousin whom I discovered in 2001. Peter can be located in the Family chart on page 6.

At top left there is a photo of John Hochee, and at the top right he is shown playing chess with George Lowdell [12031], the father-in-law of his daughter Sarah [13051 ]. Two of Hochee’s daughters married into the Lowdell family.

< Hochee playing chess with his first son, John

< Milkhouse farm cottage was given to Hochee by John Elphinstone

Nortons cottage, Milkhouse farm and Ford Manor were all given to Hochee by his benefactor.

In 1867 - two years before Ho

Greathed M ano r - bu ilt after Hoch ee’s Death

chee’s death, Ford Manor and its land were sold. The following year a new house -known as Greathed Manor (shown on the left) - was built near to Ford Manor by the new owners.

Hochee and his family were never connected with Greathed Manor, it simply marks the location of land once owned by Hochee.

18 Published privately 2002. The pictures r eproduced here are of poor quality because they were scanned from his low-resolution images in the book.

It is not known whether either Elphinstone or Ho Chee ever went abroad again. Ho Chee is always referred to as a gentleman on certificates and in Parish Registers, although he may have acted as a secretary to John Elphin -stone. Elphinstone owned several other properties in England and Scotland and it seems that Ho Chee managed Ford estate while he was away. Hoopers Farm provided a home for Charlotte' s brother Thomas Mole [12050] and his wife, and a house known as ‘Crosses’ was occupied by John Sue Achow, also Chinese, and his family.

Achow arrived later in 1832. Thorold Lowdell [13051] wrote that, when he was a boy, there were elderly residents who could recall seeing the Chinese about the village.

Ho Chee petitioned for denization on the 26 July 1839 giving his status as a yeoman and

‘reason to believe I should become possessed of Freehold Landed estate..... if the

Disability of my being alien born were removed by Letters Patent of Denization

or otherwise by Royal Concession or Favour.’

Elphinstone wrote a Deed of Gift in December 1839 giving Ho Chee his Surrey estate following his denization. It may be no coincidence that the news of the confiscation and destruction of the British opium stocks in Canton (March/April 1839) had recently arrived in England. This seizure led directly to the Opium War of 1840. Ho Chee’s position in England as a Chinese native would have been untenable in the mounting climate of war and this could have prompted his application for denization.

In 1854, events took a turn for the worse when John F. Elphinstone died at the age of 75. He was buried in the extra-mural cemetery in Brighton as he had died while staying in the town. It appears that both Elphinstone and the Hochee family often spent the winter in Brighton, as was fashionable at that time. Elphinstone willed Ford Manor, and several other properties to his friend Ho Chee. In his will he wrote:

“I, John Fullerton Elphinstone in consideration of the long and continued attachment and of the services I have received and for the attention he has given to the management and the improvement of my landed property in Lingfield Surrey On the event of my death I hereby give and devise unto Mr. John Hochee formerly of Macao and of Canton in China but for many years residing at Nortons in the Parish of Lingfield and now by her Majesty's Letters Patent a Denizen of the United Kingdom all my landed property situated in the Parish of Lingfield and County of Surrey known as Ford Farm Hoopers Crosses Nortons Milkhouse Farm together with all cottages or other appendages Manorial rights as may be thereunto belonging.”

In the same year of Elphinstone' s death (1854), their eldest daughter, Sarah, married Thorold Lowdell at Lingfield. The Lowdell family lived at Baldwins, now on the outskirts of East Grinstead, although included in Lingfield parish.

The Lowdells were land owners and also in the professions. Sarah and Thorold later moved to Woodgates Farm (also known as Milkhouse farm) which was owned by Ho Chee. On 23 August 1866, Henrietta Hochee [13039] married Sydney Poole Lowdell, who had trained as a doctor and who eventually inherited Baldwins. Members of the Lowdell family also became associated in a doctors’ practice with the Pococks in Brighton. Crawford John Pocock later married Ann Hochee [13038].

One of the unsolved mysteries of this family is that of the marriage of Letitia Charlotte Hochee [13007] to Anthony Knight. On 24 October 1860, they were married at All Souls, Marylebone; no member of either family witnessed the marriage and, if anything, it seems to have been secret. In the census of 7 April 1861 Letitia Charlotte is living at Nortons and she has been declared unmarried, presumably by her father.

Then on 1st August 1861, Anthony and Letitia married again at Lingfield, with members of both families present. It may be no coincidence that Elphinstone owned number 23 York Terrace, Regents' Park, a near neighbour of number 3 Cornwall Terrace, owned by the Knight family. Within a short time of this second wedding they emigrated to New Zealand and did not return until both their fathers had died.

On 27 July 1864, James Hochee [13008], who was by this time a surgeon, previously working in India, married Emma Fry at Redhill; they later lived at Finchley and were the only ones to perpetuate the Hochee name as John E.F. Hochee did not marry.

Around 1867, Ford Manor and the surrounding land was sold off, although various farms and cottages were kept. The following year a new house, now known as Greathed Manor, was built near to Ford Manor by the new owners.

Eventually on 1 March 1869, Ho Chee himself died whilst staying at Devonshire House, Brighton. He was buried in a grave adjoining and identical to that of his benefactor, John Elphinstone. One of the provisions of his will was:

"I give and devise unto my said wife Charlotte Hochee all that piece of Freehold

land now planted with fir on which a limekiln formerly stood situate at the cross

of roads at Dormans Land in the Parish of Lingfield in Surrey."

In the will there is no obvious reason for this but a few years after his death we find that Charlotte had the ‘Hochee Almshouses’, built on this land, and given to the village.

There were two more marriages at Lingfield; on 18 July 1871 Ann [13038] married Crawford John Pocock of Brighton while on 24 September Emily [13053] married Frank Abrahams of Croydon.

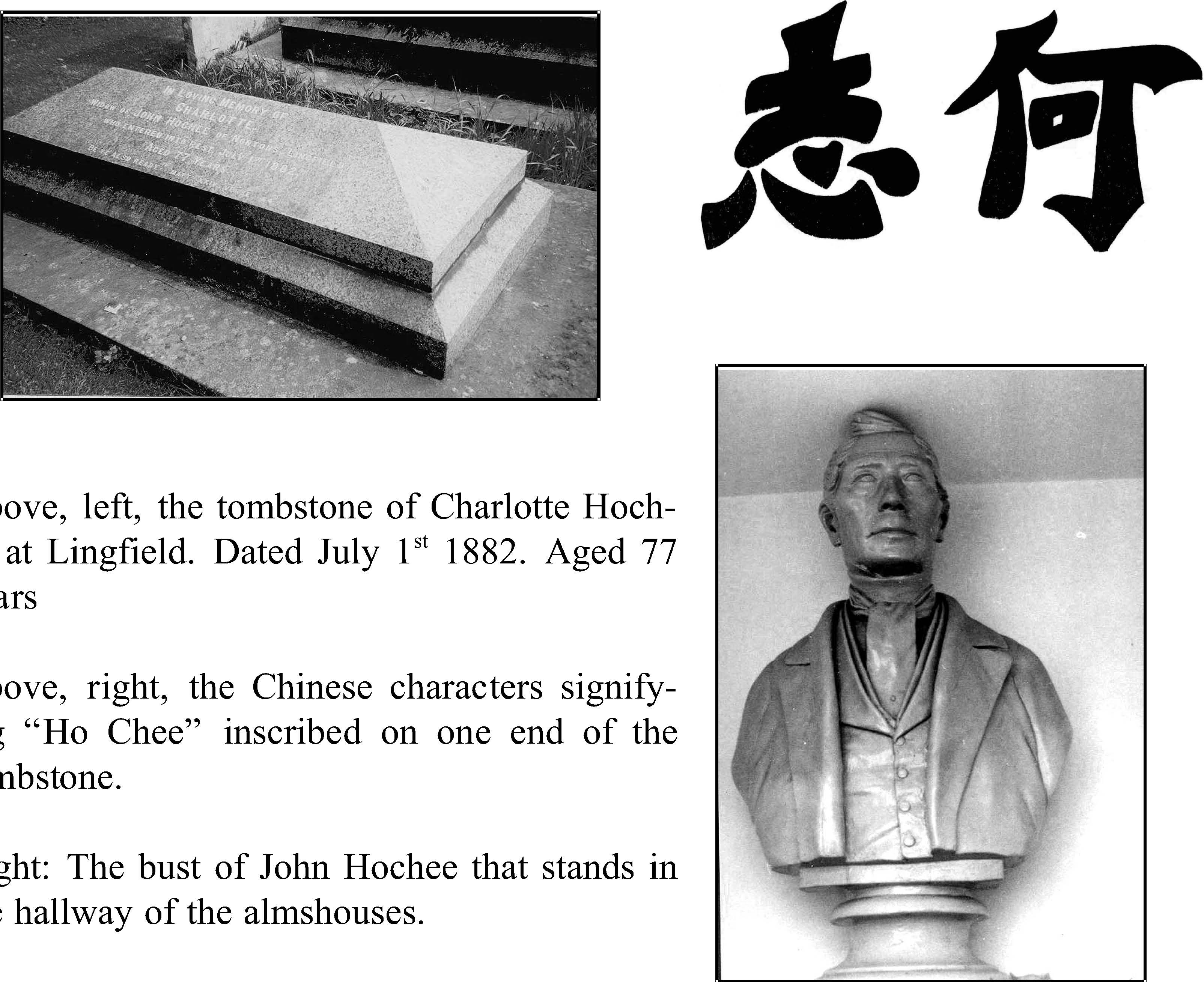

On 1 July 1882, Charlotte died at the age of 77. She was buried at Lingfield with her daughter; their grave was given a Chinese inscription which reads “Ho Chee.”

In her will Charlotte left an oil painting of Ho Chee to her sons “ with the hope that it will always remain in the family. ” Portraits of Ho Foo in Chinese robes and a smaller one of Ho Chee in Western Dress are now in the possession of the Lowdell family.

In 1882 Dormansland Church was completed with the help of contributions from local landowners including John E.F. Hochee. John E.F. Hochee died the next year at his London home, 33 Wimpole Street and he was buried with his mother in Lingfield.

The Hochee Almshouses, with a marble bust of Ho Chee himself presiding over the tiny hallway, still survive to this day providing a permanent memorial to this unusual family.

The Hochee Almshouses at Lingfield, Surrey

Above, left, the tombstone of Charlotte Hochee at Lingfield. Dated July 1st 1882. Aged 77 years

Above, right, the Chinese characters signifying “Ho Chee” inscribed on one end of the tombstone.

Right: The bust of John Hochee that stands in the hallway of the almshouses.

In

the Naturalisation records of the London Records Office there is a

letter that appears to have been written by Hochee himself applying

for citizenship. This initial application appears to have been

unsuccessful. He then employed a solicitor to write a second letter.

The record is as follows:

In

the Naturalisation records of the London Records Office there is a

letter that appears to have been written by Hochee himself applying

for citizenship. This initial application appears to have been

unsuccessful. He then employed a solicitor to write a second letter.

The record is as follows:

Ho Chee - The Petition of Ho Chee formerly of Hyan-Shan in Canton, China

but now of Nortons in the Parish of Lingfield in the County of Surrey, Yeoman.

To be a free Denizen - Awarded 21 Nov 1839

I Ho Chee of Nortons in the Parish of Lingfield in the County of Surrey, Yeoman a petitioner to Her Majesty for letters patent of Denization do solemnly and sincerely declare that I am a Native of Hyan-Shan in Canton, China that I was born of Chinese parents and am about forty-nine years of age. That I came to England in the month of August in the year one thousand eight hundred and nineteen and resided at Braughing in the County of Hertford until the year one thousand eight hundred and twenty five wherein I went to live in the Parish of Lingfield aforesaid and where I have continued to live ever since. That I have reason to believe I should come possessed of freehold landed estate either in Fee or on lease for life or years if the disability of my being alien born were removed by Letters of Denization or otherwise by Royal Concession or Favour and I further declare that I am the lawful Husband of an English Woman by whom I have a family of six children and am desirous of living permanently in England and that I am undeniably well affected to Her Majesty's person and Government and I make this solemn declaration conscientiously believing the same to be true and by virtue of the provisions of an Act made and passed in the fifth and sixth years of His late Majesty William the fourth entitled an Act to repeal an Act of the present session of Parliament entitled an Act for the more effectual Abolition of Oaths and Affirmations taken and made in various Departments of the State and to substitute declarations in being thereof and for the more entire supposition(?) of voluntary and extrajudicial Oaths and Affidavits and to make other provisions for the Abolition of unnecessary Oaths.

Declared at the Mansion House, London 23 July 1839

Ho Chee

and further,

1st August 1839

To the Right Honourable Lord John Russell Her Majesty's Principal Secretary of

State for the Home Department. The Humble Petition of Ho-Chee formerly of

Hyan-Shan, Canton, China but now of Nortons in the Parish of Lingfield in the

County of Surrey, Yeoman.